The Libertarian Party’s biennial national convention in Washington, D.C., last month was a snapshot of a minor political party in the midst of a major identity crisis.

Presumptive Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump and independent challenger Robert F. Kennedy Jr. each spoke on stage, the former landing a coveted prime-time keynote slot. Fourth-place GOP presidential finisher Vivek Ramaswamy, who keeps trying to make a “libertarian-nationalist alliance” a thing, also gave a speech.

Michael Rectenwald, the favored presidential candidate of the Mises Caucus faction currently running the party, failed to secure the nomination after making a bumbling, post-Trump speech on stage while stoned, having made a spur-of-the-moment decision beforehand to pop an edible. Longtime party activist Starchild was dragged out by security for heckling the Republican headliner. In short, it was exactly what you might have expected had you been following L.P. drama over the past few years.

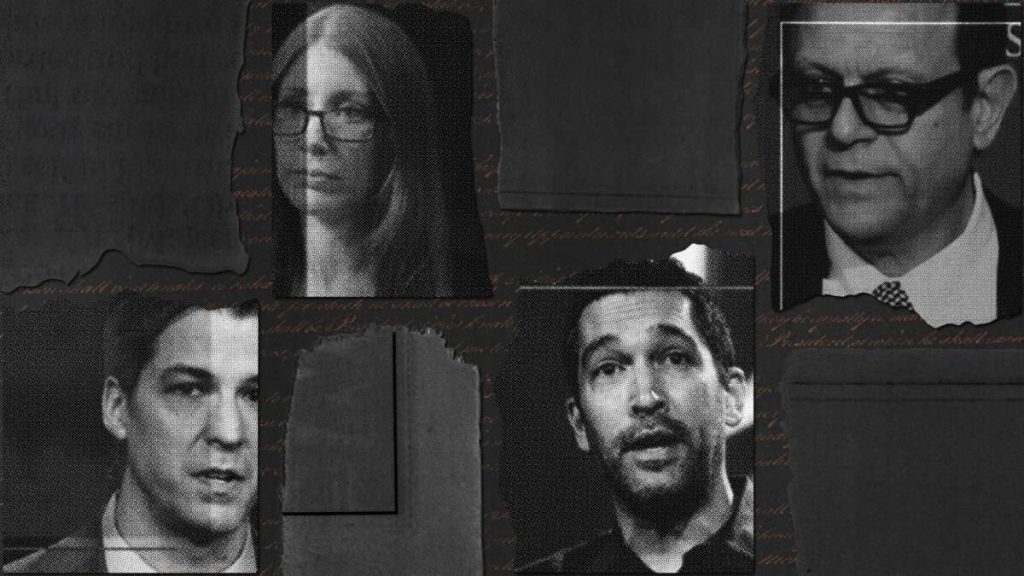

The fractured party reelected the Mises Caucus’ Angela McArdle as chair but also selected as its presidential standard-bearer Chase Oliver, a gay 38-year-old antiwar activist and former Democrat who had pushed the most recent U.S. Georgia Senate race into a runoff election eventually won by a Democrat.

In the past three presidential elections, the Libertarian candidate appeared on all 50 state ballots plus the District of Columbia, finished in third place, and was backed by every state L.P. affiliate. None of that seems likely to happen this year.

The Montana L.P. after the convention immediately declared that it would not be placing Oliver’s name on the ballot. “Similarly situated states should follow our lead,” the state party wrote. “We call upon the [Libertarian National Committee] to consider suspending and replacing him.” So far, one state—Colorado—has followed suit, charging Oliver and running mate Mike ter Maat with being “useful idiots for the regime” who are “unfit to represent our values.” Idaho is contemplating whether to do the same and putting pressure on the national party to remove Oliver from the ballot. The Libertarian Party of New Hampshire is predictably vocalizing its distaste and intent to siphon resources away from the candidate, but Oliver is still filing his intent to run with the secretary of state there.

Oliver “doesn’t represent me and my camp or the things we stand for,” comedian/podcaster Dave Smith, who the Mises Caucus had once pinned its hopes on for the 2024 nomination, wrote after the convention. “Look, if us taking over the whole party, if the outcome was this,” Smith elaborated on his podcast, “then there’s only one word to use to describe that, and that’s failure.”

Oliver’s critics say he’s culturally woke and was insufficiently opposed to the COVID regime of lockdowns, vaccine mandates, and masking. “I’ve been against vaccine or mask mandates from government,” he countered to me and Zach Weissmueller on our show, Just Asking Questions. “If the COVID messaging was so good—this divisive messaging saying, If you wore a mask, if you ever took a vaccine, you’re just an idiot and you’re stupid or whatever—that’s what [the Mises Caucus is] putting out there. And guess what? We’re bleeding members and donors because people want to make decisions for themselves and not be shamed that they made a decision differently than their neighbor.”

Meanwhile McArdle, against a pre-convention backdrop of declining party membership, fundraising, and ballot access, has portrayed last month’s gathering as a triumph, while positing Oliver as a tool for siphoning away votes from President Joe Biden.

“Donald Trump says he’s going to put a Libertarian in a Cabinet position. He came out and spoke to us. He said he’s a Libertarian. He has basically endorsed us,” McArdle said in a June 3 video address. “And so in return, I endorse Chase Oliver as the best way to beat Joe Biden. Get in loser, we are stopping Biden. That’s what I think. That’s what I think this campaign is about.”

How did the party get here, to a place where its chair is openly cheering on victory for the decidedly nonlibertarian Trump?

The modern-day fracture of the L.P. started in 2017, when a small bloc formed the Mises Caucus, lionizing such figures as Ron Paul and Murray Rothbard. Generally young and extremely online, culturally right of center, attracted to sharp-elbowed podcasters like Smith and Tom Woods, the Mises crew exudes visceral hostility toward the state, the Fed, the war machine, and what they see as the philosophically compromised D.C. libertarian think-tankers (pejoratively termed “Beltwaytarians”) who they believe enable rather than meaningfully oppose the “regime.”

The Mises Caucus arose in revulsion toward the Gary Johnson/Bill Weld 2016 ticket, which they saw as having watered down the libertarian message to the point of being unrecognizable. They were further disappointed by 2020 nominee Jo Jorgensen and downright repulsed by the L.P.’s messaging on Black Lives Matter and COVID lockdowns.

In 2022, the Mises Caucus succeeded in a self-styled “takeover” of the party at its convention in Reno, after which the victors wasted little time inflaming the sensibilities of what they saw as the losing libertines. No more overemphasizing the importance of sex work, abortion, or free-flowing immigration, positions the new guard either disagreed with or felt needlessly alienated potential allies.

But the Reno Resetters, in their bid to reinvigorate the party, were doing plenty of alienating of their own—of longtime Libertarian Party donors and volunteers who did not share the Mises Caucus’ preference for meme clapbacks and helicopter jokes.

I chatted with a few of these disgruntled activists about why they pulled their time and money away from the L.P., whether the mixed results from the latest convention gave them reason to hope, and whether there’s any way for the fractured party to mend itself.

“I became a libertarian because the authoritarian conservative politics I grew up in didn’t resonate with me,” says Christian Bradley, who started voting Libertarian and volunteering for the party in 2008. But the Mises Caucus has injected “authoritarian conservative politics into the party,” Bradley says, transforming it into more like a “twisted social club” for “MAGA edgelords” than something that represents his beliefs.

Libertarian Party–affiliated instances of social media edgelording are almost too numerous to count, whether it’s riffing on Adolf Hitler’s 14 words, or calling the Uyghur genocide “war propaganda,” or telling a black congresswoman to go pick crops, or tweeting out “let Ukraine burn,” or calling that country “gay,” or telling columnist Max Boot to go kill himself, or advocating prison time for Liz Cheney, or fantasizing about sending ex-presidents to Gitmo.

Other edgelording happened behind closed doors, pushing staffers and volunteers away from the party at a time when the organization needed all the help it could get.

“In April 2022, the last full month before the Mises Caucus takeover, the L.P.’s end-of-month financial report listed revenues of $125,542,” reported Reason‘s Brian Doherty last month. “In April 2024, that figure was $84,710, a drop of nearly one-third. The number of sustaining members (those who have donated at least $25 in the past year) has fallen from around 16,200 in April 2022 to 12,211 in April 2024.”

Forty-year-old Ryan Cooper met his now-wife, Casie, while doing outreach for the Jo Jorgensen campaign. “From 2016 to 2021, I gave over $50,000 and countless volunteer hours,” Cooper says. But now, the couple no longer wants to be associated with “an organization that supported racists, bigots, white nationalists, and [Vladimir] Putin apologists.”

The Washington state Libertarian Party has become hollowed out, Cooper contends, with massive declines in attendance at state conventions, all county chapters shuttered except for just two, and zero nonpresidential Libertarians on the 2024 statewide ballot, compared to over 50 in 2016. Even gaining ballot access for Chase Oliver is no longer a sure thing in the Evergreen State, he says.

Cooper has donated $1,000 to Oliver and said that the reactions by some Mises Caucus types to the candidate—calling him a “cultural Marxist” and “woke homosexual,” for instance—helped convince him to become a volunteer for the campaign. He maintains that he won’t donate money to the national party until McArdle is no longer chair.

Mark Tuniewicz, a former finance executive based in South Dakota and member of the L.P. since 1994, tells me he notified the party at the start of this year that he had rescinded his decision to bequeath $650,000 to them in his will; with the takeover, he just doesn’t believe the organization is serving his values any longer. Tuniewicz served, up until last month, on the Libertarian National Committee (LNC). “No accountability metrics lead to poor execution and results,” he says. There’s been “unprecedented organizational dysfunction, resulting in huge turnover on the LNC.” And, as he wrote in his letter rescinding his donation, the L.P. has been “corrupted organizationally in a way from which it may never recover.”

“I stopped donating after the [Mises Caucus] takeover in Colorado in 2021,” says Alan Hayman, who’s given $3,000 over the years. The state affiliate “proved to be woefully incompetent, wanting to reinvent the wheel on everything, and…developed a habit of gaslighting and mistreating members,” Hayman says. “They were rude to party veterans, but also felt entitled to their time and knowledge.”

Bureaucratic sloppiness led to the party being fined by the Colorado secretary of state $12,500 for late donation filings, part of a nationwide pattern of increased spending on noncore activities. Over the first four months of 2024, the national party spent $10,350 on the bread-and-butter line item of securing ballot access while shelling out $24,807 in legal expenses.

That lack of emphasis on ballot access is having real effects; on June 13, the New York State Board of Elections declared that the L.P.’s petition for ballot access had insufficient signatures, marking the first time in party history that its presidential candidate has failed to appear on the New York ballot.

Some of those legal expenses are coming from the national party suing a faction of the Michigan L.P. that’s not under Mises Caucus leadership, but which insists it is legally the state party affiliate. In Michigan, a Mises-affiliated person, Andrew Chadderdon, in 2022 ascended to state chair, due to resignations on the state board. Despite a critical mass of the state delegation voting to remove Chadderdon, the national party continued to recognize him as chair. The national party filed a lawsuit; the state party has been holding separate conventions ever since.

“I am a strong believer in voting with feet, dollars, attention,” former party activist Casey Crowe says. “The last two years have given me no reason to continue my financial investment when it’s spent on suing affiliates, instead of functional needs like ballot access.”

Many of the disgruntled Libertarians point their ire at McArdle. “Nobody knows what she does,” former L.P. employee Michelle MacCutcheon tells me. MacCutcheon, who had been in charge of onboarding all new volunteers (a “labor of love,” as she described it), said the new regime carried out a purge of staffers, with little respect given to coalition building or professionalism. (McArdle, for instance, hired her own romantic partner as a contractor to help with fundraising). “We were on a great trajectory” before, MacCutcheon says. “All of that was just wiped clean.”

But, counters Florida L.P. member John Thompson, who is more agnostic on the results of the takeover, “If [McArdle] is as bad as they say, then they should have a solid game plan to defeat her and elect a new chair.” Instead, she won on the second ballot during the D.C. convention, with 53.44 percent of the vote.

The fractures within the Libertarian Party are likely to deepen over the final 20 weeks of the presidential campaign. But the overall picture remains mixed—for instance, L.P. Communications Director Brian McWilliams tells Reason that fundraising is up 16 percent post-convention. A little post-convention bump is, of course, to be expected if historical trends are any indicator. “The 2024 convention will likely rival 2022 for the highest-fundraising convention in the history of the party,” wrote Todd Hagopian, the LNC’s pre-convention treasurer, in internal emails updating other members. But “the 2024 convention will be the most expensive convention in the history of the party,” due to its location in D.C., and the party “will probably not net as much net income” this year compared with 2022.

It’s unlikely that the millions of Americans who have been voting Libertarian for president the past three cycles are even worried about, let alone paying attention to, the party’s internal tensions.

But for some activists, there’s no reason to continue fighting for a party that feels so far gone.

“I’m not even comfortable using the word ‘libertarian’ to describe myself, after all the damage the [Mises Caucus], LP, and MAGA have done to the word and scene,” Bradley says. “At best, members of Mises Caucus are willing to tolerate and associate with known white supremacists, antisemites, Holocaust deniers….At worst, they are those people.”

The post How the Libertarian Party Lost Its Way appeared first on Reason.com.