On July 10, U.S. District Court Judge Mark Pittman in the Northern District of Texas ruled in the case of Hobby Distillers Association v. Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau that the longstanding federal ban on home distillation of alcohol for drinking is unconstitutional. The ruling raises nuanced legal questions that will almost certainly be scrutinized on appeal. It also provides an occasion to ask a more fundamental question: Why is distilling spirits in one’s own home for personal use any of the government’s business?

The plaintiffs, which included aspiring home distiller Scott McNutt as well as the association, challenged two provisions of federal law. The first forbids locating a licensed spirits plant “in any dwelling house, in any shed, yard, or inclosure connected with any dwelling house.” The second makes it a criminal offense for anyone to use, or possess with intent to use, distilling equipment for the production of spirits, punishable by fines of up to $10,000 or up to five years in prison. Together, these provisions make any sort of home distilling illegal.

Pittman argues this prohibition can’t be justified under Congress’ taxation power or the Commerce Clause. Regarding the former, Pittman notes that while the prohibition may help combat tax evasion, it is not itself a tax and prevents home distillers from making reasonable efforts to welcome inspection of, and then pay taxes on, any spirits they produce. “Thus,” he concluded, “Congress did nothing more than statutorily ferment a crime—without any reference to taxation, exaction, protection of revenue, or sums owed to the government.”

Pittman’s decision tried to distinguish this case from the unfortunate Commerce Clause precedent granting the government expansive power to regulate private, noncommercial activity because of alleged connections to interstate commerce. The Supreme Court had in Wickard v. Filburn (1942) upheld penalties against a farmer for growing wheat for his own noncommercial use, and in Gonzales v. Raich (2005) the Court approved federal prohibition of home-grown medicinal cannabis. Those personal activities, the Court insisted, had substantial carryover effects on interstate commerce.

Pittman distinguishes the home distillation ban from those precedents by contending that the government does not “comprehensively” regulate the market for spirits as it did the markets for wheat during the New Deal or for cannabis today. Those comprehensive regulations concerned the supply and demand of products on a national level; the federal goal was to keep wheat prices high or to eliminate cannabis supply entirely.

The ban on home distilling, though, Pittman writes, “does not directly regulate the supply and demand of alcohol, does not make Congress a production manager over each distillery to inflate prices, and is not part of a federal directive to either promote or eliminate a national marketplace for alcohol” and thus doesn’t fall under even the expansive Commerce Clause doctrine established in Wickard.

Before rushing out to buy a copper still and an American oak barrel to make your own bourbon, note that the ruling only enjoins enforcement of the laws against the current plaintiffs. Even if this ruling survives a likely appeal, the government can still tightly regulate home distillation by requiring registration, inspection, and compliance with other liquor laws.

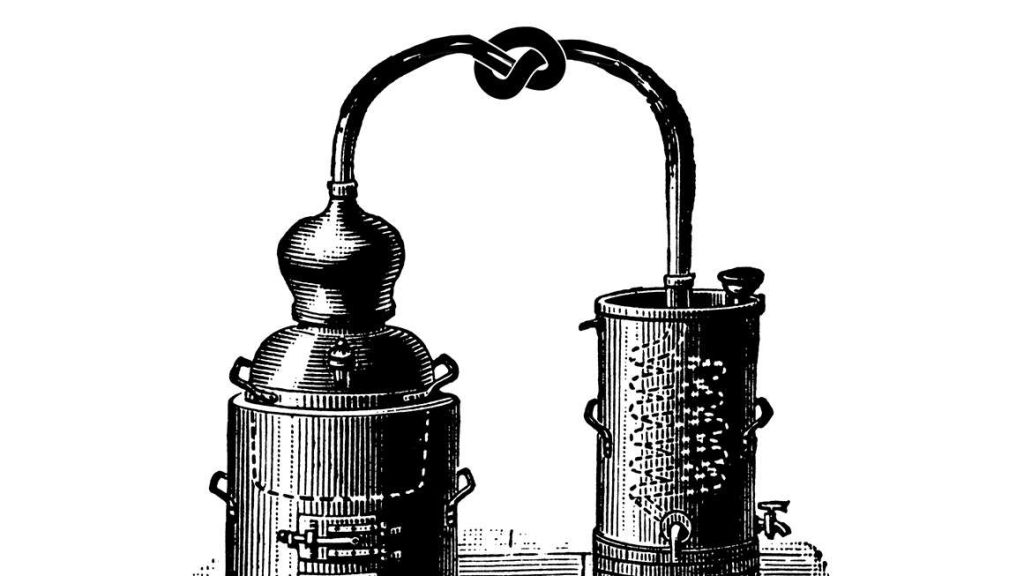

Why shouldn’t we be able to make spirits at home? Small-scale home distillation has a long history in the United States and can be done responsibly. Dangerous beverages more typically arise from prohibition, as when legally mandated denatured alcohol poisoned imbibers during the Prohibition era, or when criminal bootleggers spike their product with methanol or other toxicants.

Professional distillers aren’t so much worried that an amateur might make unsafe booze as that they might blow themselves up. “Culturally, we do a lot of dangerous activities,” says Tom Burkleaux, founder of New Deal Distillery in Portland, Oregon, and president of the Oregon Distillers Guild. “Deep-frying turkeys. Firearms. Power tools. But they’ve been around long enough that people understand the risks.”

Burkleaux worries that many Americans aren’t in firm command of best practices to minimize dangers when working with heat sources and highly flammable alcohol vapor. The culture of discreet moonshining may further encourage risky behavior, such as distilling in a home or shed rather than outdoors or in a space with better ventilation.

Andy Garrison, head distiller of Stone Barn Brandyworks and owner of Tuff Talk Distilling (both in Portland, Oregon) hopes that trade groups will step up to educate home distillers in a legal environment. “If it was legal,” he speculates, “there would be someone setting up small-scale manufacturing and making ultra-expensive hobby stills.”

Garrison isn’t sure legalization will create a huge wave of new home distillers. Various voices in the professional distilling space agreed that home alcohol making wouldn’t save money for practitioners, especially when one factors in time and equipment costs. The consumer context for home distilling today also differs considerably from when home brewing beer was legalized in 1978. In that dismal era of American beer, if you wanted alternatives to mass market lager, your best option often really was to make it yourself. One can’t say the same of the contemporary spirits market, which is awash in high-quality and often extremely niche offerings.

Nonetheless, many Americans have given it a try despite its illegality. “It’s a little bit of sticking your finger to the man, and that’s kind of fun sometimes,” one amateur distiller tells Reason. “There’s no practical reason to be distilling at home. The only reason to do it is because you love it as a hobby or get personal satisfaction out of it,” especially since indulging this hobby could net you up to five years in prison.

Home brewing beer provides a model for reform. Under federal law, adults can brew up to 100 gallons of beer annually for personal noncommercial use, with no requirement to register with or pay taxes to the government. Congress could set proportional limits for home distilling. Another model is New Zealand, which legalized home distilling in 1996. The sky has not fallen, and a hobbyist culture has bloomed. The same could happen in the United States.

“I moved to New Zealand [from the U.S.] in 2003. Home distillation has been legal for longer than I have been here,” says Eric Crampton, chief economist at The New Zealand Initiative.” It is about time that Americans also get to enjoy this freedom.”

The post Longtime Ban on Home Distilling May Finally End appeared first on Reason.com.