November 1959. Film director Alfred Hitchcock is at his commercial and critical peak after the successes of Vertigo (1958) and North by Northwest (1959).

So what does he do next?

A black-and-white made-for-TV movie hastily shot, with no big-name actors and a leading actress who takes a shower, and … well, we’ll come to that.

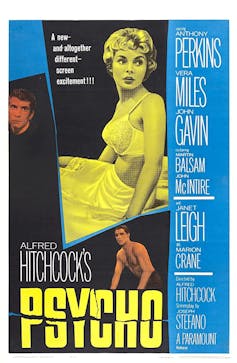

Psycho (1960) remains Hitchcock’s most celebrated film.

But it is really two films, glued together by the most iconic scene in cinema history.

Part one is a run-of-the-mill morality tale.

Marion Crane (Janet Leigh) steals $40,000 from her Phoenix employee, and goes on the run.

Guilt-stricken, she pulls into a deserted motel and chats with the owner, Norman Bates (Anthony Perkins).

He seems friendly enough – he makes her sandwiches and talks fondly about his mother – and Marion resolves to return the money.

Part two is a whodunnit. Marion’s sister (Vera Miles) and her lover (John Gavin) investigate her disappearance, and trace her steps back to the motel.

Soon, they begin to have suspicions about Norman.

Thriller with a twist

A few years earlier, Hitchcock had watched Henri-Georges Clouzot’s 1955 psychological masterpiece Les Diaboliques and sought out a similar project – a horrific thriller with a twist ending.

He read Robert Bloch’s novel Psycho – itself inspired by the real-life Wisconsin killer Ed Gein – and optioned the film rights.

Audiences saw things in Psycho that had never been shown before on screen.

A toilet flushing. A murderer who goes unpunished. A post-coital Leigh, lying on a bed, dressed only in white underwear, while Gavin stands topless over her.

All of Hitchcock’s trademark obsessions are on show: Voyeurism, the dominant matriarchal figure, the blonde heroine, the untrustworthy cop.

Over his career, Hitchcock had always flouted Hollywood’s Production Code, those rigid rules that had been in place since the 1930s that prohibited onscreen nudity, sex and violence.

Nowhere is Hitchcock’s brazen censor-defying clearer than in Psycho’s “shower scene”.

Marion steps into the shower, a shadowy figure rips back the curtain, and cinema’s most visceral scene unspools, brutally, before our very eyes.

Hitchcock, the master of suspense, never actually shows knife slicing flesh.

Everything is implied, through liberal doses of chocolate sauce, hacked watermelons, Bernard Herrmann’s screeching violins, and Leigh’s blood-curdling screams.

In one 60-second scene, Hitchcock shatters all the rules.

It’s the most famous of all bait and switches: You expect one thing, but get another.

Up to that point, no film had killed off its lead character so early in the story (nowadays, such an audacious twist shows up everywhere, from The Lion King to Games of Thrones).

As Leigh slides down the blinding white tiles, arm outstretched, a new kind of cinema is born: Twisted, shocking, primal.

Inventing the cinema event

Hitchcock famously ordered cinemas to not let any latecomers into screenings of Psycho, to keep the element of surprise.

Previously, cinema-goers could wander into a film midway through, watch the last half, and then stick around for the restart to catch up on what they had missed.

When your leading lady is butchered 45 minutes in, the film makes little sense if you arrive late – hence Hitchcock’s decree.

There were queues around the blocks in cities across America as word of mouth grew. Grossing $US32 million (equivalent to $468 million today) off a budget of US$800,000 ($12 million today), Psycho made Hitchcock a very wealthy man.

Other elements contributed to Psycho’s enduring influence.

Saul Bass’s opening credits, all intersecting lines and sans-serif titles, anticipate the film’s fixation with duality and overlap.

Budget constraints meant that Herrmann could only rely on his orchestra’s string section. Even people who have never seen the film instantly recognise his score.

And Anthony Perkins, typecast forever after as the nervous mother’s boy with a dark secret, crafts a performance that is both sweetly disarming and deeply unsettling.

Psycho sequels

Its reputation has only grown since 1960. Critics and audiences remain transfixed by Psycho’s storytelling verve and its queasy tonal shifts (murder mystery to black comedy to horror).

Douglas Gordon’s 1993 art installation 24 Psycho slowed the film down to last a full day.

Academics have had a field day too, from Raymond Durgnat’s lengthy micro-analysis to Slavoj Žižek’s reading of Bates’ house as an illustration of Freud’s concept of the id, ego and superego.

Three progressively sillier sequels were made, as well as a colour shot-for-shot remake by Gus van Sant in 1998.

Brian De Palma’s entire back catalogue pays homage to Hitchcock, with whole sections of Sisters (1972) to Dressed to Kill (1980) reworking Psycho’s delirious excesses.

Psycho’s box office success undoubtedly contributed to Hollywood’s abiding fascination with true-crime stories, serial killers and slasher films.

More recently, the TV prequel series Bates Motel ran for four seasons, deepening Norman’s relationship with his mother and tracking his developing mental illness.

That series provides a set up for the events at the Bates Motel.

Sixty years on, the setting for Psycho continues to exert such a pulsating thrill, even as we watch from behind the sofa.

_____________________________________________________________________![]()

Ben McCann, Associate Professor of French Studies, University of Adelaide

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons licence. Read the original article.

The post <i>Psycho</i> turns 60 – Alfred Hitchcock’s famous fright film broke all the rules appeared first on The New Daily.

Powered by WPeMatico