STR/NurPhoto via Getty Images

- Naval mines being used off of Ukraine’s and Russia’s Black Sea coasts appear to drifting away.

- Mines are hard to find and neutralize, and when they go astray they are highly disruptive to maritime traffic.

Some of the most dangerous weapons deployed in Russia’s war on Ukraine are affecting the entire Black Sea region, as naval mines used in the conflict are drifting hundreds of miles away.

Ukraine and Russia share the Black Sea coast with Georgia and NATO members Romania, Bulgaria, and Turkey, which controls the straits that connect the sea to the Mediterranean and beyond.

Since the beginning of the war four mines have floated away from Ukrainian waters. One was found off of Romania’s coast and three in Turkish waters. Stray mines can cause significant disruptions to maritime traffic in the region.

Lethal visitors

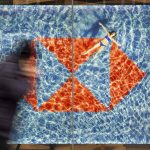

Muhammed Enes Yildirim/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

Naval mines are asymmetric weapons that can cause damage to naval vessels disproportionate to the mines’ cost.

Finding and neutralizing them is difficult and time-consuming, meaning they can hinder or deny the access of much more sophisticated naval vessels to certain areas.

They come in many varieties and can be deployed at various depths or on the surface by mine-laying vessels or aircraft. Most older models detonate on contact. Newer models can detonate based on pressure changes, sounds, or magnetic waves produced by an approaching object.

Older, less sophisticated mines can cause significant damage, though it depends on their size, age, and proximity to target.

Newer, more powerful mines can do more damage to a vessel with the shock waves they produce or through bubble jet damage, which is caused by water rushing back into the space created by the mine’s explosion.

Hristo Rusev/Getty Images

The outsize effectiveness of naval mines was demonstrated in 1988, when US Navy frigate USS Samuel B. Roberts hit an Iranian mine in the Persian Gulf. The frigate was crippled and narrowly avoided sinking. Repairs took six months and cost nearly $90 million. The Iranian mine had an estimated cost of only $1,500.

All four stray mines detected in the Black Sea so far have been Soviet-made anchor contact mines, which are designed to float just below the surface. They appeared to be in poor condition, which may have made them more dangerous.

Speaking to Deutsche Welle, Johannes Peters, a maritime strategy expert at the University of Kiel, said the Black Sea’s salinity combined with the mines’ age and condition considerably increases their sensitivity.

It is not clear whether the four mines belonged to Ukraine or Russia. Each side has accused the other of employing them. As of mid-March, there were more than 400 mines in the Black Sea, according to a Russian navigational notice, with about 10 of them already adrift.

Not as easy as minesweeper

US Navy/Mass Comm Specialist 2nd Class Corbin Shea

Locating and disabling naval mines, especially modern ones, is a challenge that often requires coordination between aerial and naval assets. The task becomes even more difficult if the area to be searched is large and the presence of mines is uncertain.

The most common and safest method of mine location is by mine-hunting vessels or aircraft equipped with high-fidelity sonars. To minimize the risk of triggering a nearby mine, mine-hunting vessels are designed to have a low magnetic and acoustic footprint.

Once a mine is located, it can be disabled by a controlled explosion performed by a diving team or in some cases by remotely operated underwater vehicles. Novel mine-hunting platforms include unmanned surface vessels and submersibles as well as dolphins and sea lions trained to detect mines.

Mine-hunting is a slow process, which magnifies its disruptive effect, as maritime traffic through the area being searched is delayed or has to be re-routed. They are especially disruptive in heavily trafficked maritime arteries, like the Bosporus, one of the Turkish straits between the Black and Mediterranean Seas.

One of the mines that drifted away from Ukrainian waters was found near the Bosporus. Turkish authorities had to temporarily close the busy strait while the Turkish Navy disabled the mine.

A neglected field

US Navy/Lt. j.g. Alexander Fairbanks

The Turkish Navy has a strong anti-mine warfare component, with 11 relatively new mine-countermeasure vessels. Other navies, including the US’s, have neglected anti-mine warfare.

Despite its size and budget, the US Navy only has eight Avenger-class mine-countermeasure vessels. All of them are roughly 30 years old and need frequent repairs, rendering them largely ineffective. Its Sea Dragon mine-countermeasure helicopters are also aging and face similar challenges.

The need to modernize US mine-countermeasure capabilities is made more pressing by US adversaries’ extensive use of mines. Russia, China, and North Korea all have large arsenals — Russia’s is the largest, with estimates of its size ranging from 125,000 mines to a million.

As Russia’s war in Ukraine continues, the risk posed by both sides’ mines persists and may worsen. NATO’s Shipping Center, the alliance’s liaison to the merchant shipping community, has said “the threat of additional drifting mines cannot be ruled out.”

Constantine Atlamazoglou works on transatlantic and European security. He holds a master’s degree in security studies and European affairs from the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy.

Powered by WPeMatico