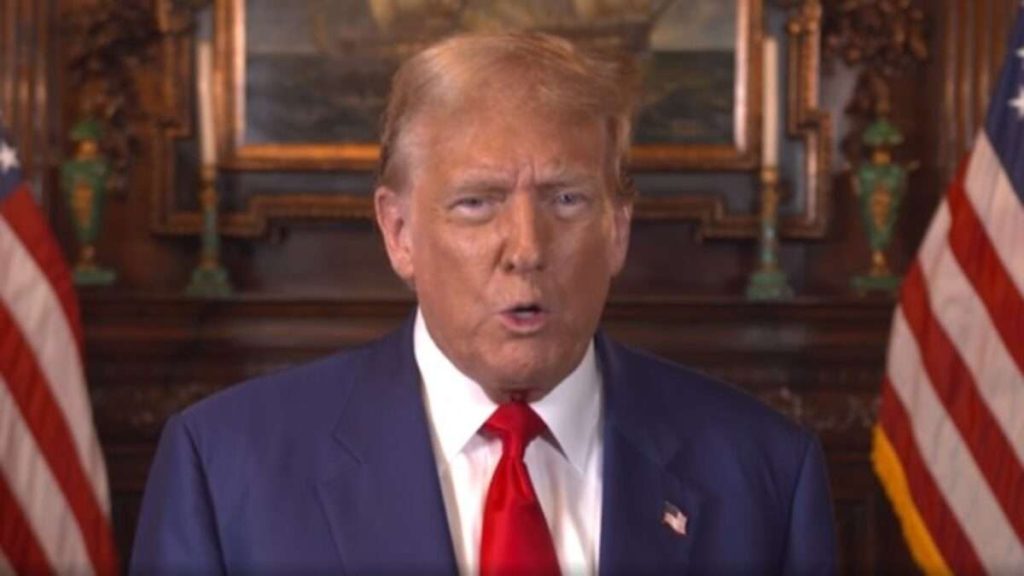

In a Truth Social video posted this morning, Donald Trump says abortion policy should be left to the states. The result, he noted, will be a wide range of restrictions, with different states drawing lines at different points in pregnancy. Although he does not say which cutoff he prefers, he has previously said Florida’s “heartbeat” law, which applies around six weeks of gestation and prohibits most abortions, is “a terrible thing and a terrible mistake.” And in the Truth Social video, he says that “like Ronald Reagan, I’m strongly in favor of exceptions for rape, incest, and life of the mother.”

By ruling out federal abortion restrictions, Trump provoked criticism from pro-life activists who favor a national ban. But those activists will never support Joe Biden, who not only views the 2022 reversal of Roe v. Wade as a grave injustice but favors legislation that would re-establish a federal right to abortion. Trump is clearly more worried about alienating voters who oppose broad restrictions on abortion, which surveys suggest is most of them.

During a Meet the Press interview last September, Trump, who once described himself as “pro-choice,” declined to say whether he would “sign federal legislation that would ban abortion at 15 weeks.” But he said he would “come together with all groups” to arrive at “something that’s acceptable,” implying that he was open to the idea of federal restrictions. Now he is saying “the states will determine [abortion policy] by vote or legislation, or perhaps both, and whatever they decide must be the law of the land,” meaning “the law of the state.” The bottom line, he says, is respecting “the will of the people.”

Reversing Roe, Trump argues, served that end by freeing states to regulate abortion as they see fit. Through his Supreme Court appointments, he brags, “I was proudly the person responsible for the ending of” Roe. That result, he claims, was “something that all legal scholars” on “both sides” favored.

That is obviously not accurate. While it is true that some supporters of abortion rights criticized Roe‘s reasoning, that does not necessarily mean they thought the Constitution was irrelevant to the debate. As an appeals court judge, for example, the late Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg argued that Roe went too far, too fast, and she favored grounding a constitutional right to abortion in the 14th Amendment’s guarantee of equal protection rather than an unenumerated right to privacy or bodily autonomy. But Trump’s claim of bipartisan agreement that Roe was wrongly decided reflects his attempt to align his position with what he thinks most Americans want.

In the latest Gallup poll, 52 percent of Americans described themselves as “pro-choice,” while 44 percent identified as “pro-life.” Thirty-four percent said abortion should be “legal under any circumstances,” compared to 13 percent who said it should be “illegal in all circumstances.” A majority (51 percent) said abortion should be “legal only under certain circumstances,” a view that encompasses a wide range of policies.

That majority position could describe a broad ban with the exceptions that Trump supports, for example, or a much more liberal policy that generally allows abortion through 20 weeks of gestation, which would cover nearly all abortions. Even the 15-week limit that Florida’s Supreme Court recently upheld would allow something like 96 percent of abortions. By contrast, Florida’s “heartbeat” law, which will take effect unless voters approve an abortion-rights ballot initiative in November, covers a much larger share of abortions. According to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 55 percent of abortions are performed after six weeks. The ban also would apply to some abortions performed at six weeks or earlier.

All of those policies could be described as making abortion “legal only under certain circumstances.” But Gallup also found that 47 percent of Americans thought abortion should be legal in “any” or “most” circumstances, which would rule out the law that Trump deemed “a terrible mistake.” Another 36 percent said abortion should be legal “only in a few circumstances,” which could mean a six-week ban or even a general prohibition with limited exceptions.

“When asked about the legality of abortion at different stages of pregnancy,” Gallup reports, “about two-thirds of Americans say it should be legal in the first trimester (69%), while support drops to 37% for the second trimester and 22% for the third. Majorities oppose abortion being legal in the second (55%) and third (70%) trimesters.”

We also know that even voters in red states, expressing their preferences at the ballot box rather than in surveys, have opposed stricter abortion policies. In August 2022, a little more than a month after the U.S. Supreme Court overturned Roe in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, Kansas voters overwhelmingly rejected a ballot initiative that would have overriden a 2019 ruling in which the state Supreme Court held that the Kansas Constitution protects a right to abortion. That November, Montana voters rejected an initiative that would have recognized “infants born alive” after an “attempted abortion” as “legal persons” and imposed criminal penalties for failing to provide them with “medical care.” Kentucky voters, meanwhile, rejected an initiative declaring that the state constitution does not guarantee a right to abortion. And in Ohio last November, voters approved an initiative amending the state constitution to protect “reproductive decisions,” including abortion.

More generally, Democrats seem to have reaped an electoral benefit by emphasizing abortion rights, boosting turnout among voters inclined to support them. That factor helps explain why Democrats performed better than expected in the 2022 midterm elections and why they won important state races in Kentucky, Virginia, and Pennsylvania last fall.

Dobbs is “wreaking electoral havoc, shifting partisan calculations, and calling into question balances of federal and state power,” Reason‘s Elizabeth Nolan Brown noted last year. “It’s also ushering in a new level of representative democracy in determining the limits of reproductive freedom—along with a backlash to the process that could reach far past policies surrounding abortion.” The upshot, she suggested, “could better reflect the underlying political reality that American opinions about abortion are complex, nuanced, and not terribly extreme.”

In this context, you can see why Trump’s position, which embraces a federalist approach without endorsing any particular policy aside from rape, incest, and life-of-the-mother exceptions, makes political sense. It also jibes with what the late Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia, a longtime Roe foe, imagined would happen after that decision was overturned. Scalia complained that Roe “destroyed the compromises of the past, rendered compromise impossible for the future, and required the entire issue to be resolved uniformly, at the national level.”

In Dobbs, Justice Samuel Alito agreed with Scalia that the Constitution does not limit how far the government can go in regulating abortion. But his majority opinion was ambiguous in describing what would happen next. “It is time to heed the Constitution and return the issue of abortion to the people’s elected representatives,” he wrote. That formulation, which could refer to members of Congress as well as state legislators, left open the possibility that “the entire issue” would be “resolved uniformly, at the national level.” This is the possibility that Trump has now joined Scalia in rejecting.

Although we should not credit Trump with caring much about what the Constitution requires, the legal rationale for national abortion legislation has always been dubious. The Partial-Birth Abortion Ban Act of 2003, for instance, prohibits certain kinds of late-term abortions “in or affecting interstate or foreign commerce”—an attempt to justify the law by invoking the power to regulate interstate commerce. As Independence Institute scholar David Kopel and University of Tennessee law professor Glenn Reynolds have noted, that language is baffling “to any person not familiar with the Commerce Clause sophistries of twentieth century jurisprudence,” since “it is not really possible to perform an abortion ‘in or affecting interstate or foreign commerce'” unless “a physician is operating a mobile abortion clinic on the Metroliner.”

When Sen. Lindsey Graham (R–S.C.) proposed a 15-week federal abortion ban in 2022, he invoked the 14th Amendment’s guarantees of due process and equal protection. Those guarantees apply to “any person,” which in Graham’s view includes fetuses (or, as he prefers, “unborn children”). Although some abortion opponents have long favored that interpretation, the Supreme Court explicitly rejected it in Roe and has yet to revisit the issue.

Many of Graham’s fellow Republicans were dismayed by his attempt to renationalize the abortion issue. “I don’t think there’s an appetite for a national platform here,” said Sen. Shelley Moore Capito (R–W.Va.). “I’m not sure what [Graham is] thinking here. But I don’t think there will be a rallying around that concept.”

Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R–Ky.) likewise said most of his Republican colleagues “prefer this be handled at the state level.” Those Republicans included Sen. John Cornyn (R–Texas), who said “there’s obviously a split of opinion in terms of whether abortion law should be decided by the states.” He added that “my preference would be for those decisions to be made on a state-by-state basis.”

Graham’s bill, which attracted just nine co-sponsors, never made it out of committee. And now Trump has made it clear that he opposes such legislation.

Biden, meanwhile, continues to support legislation that would renationalize the abortion issue in the opposite direction. A 2022 bill, for example, would have prohibited states from banning or regulating abortion prior to “viability,” which nowadays is generally said to occur around 23 or 24 weeks into a pregnancy. It failed by a 49-to-51 vote in the Senate.

That bill would have gone even further than Roe and its progeny, which allowed restrictions on pre-viability abortions as long as they did not impose an “undue burden” on the right to terminate a pregnancy. And it would have overriden regulations that most Americans seem to favor.

The bill’s sponsor, Sen. Richard Blumenthal (D–Conn.), did not even bother to provide a constitutional pretext. But a different version of the bill, which the House passed in 2021, framed it as an exercise of the power to regulate interstate commerce:

Abortion restrictions substantially affect interstate commerce in numerous ways. For example, to provide abortion services, health care providers engage in interstate commerce to purchase medicine, medical equipment, and other necessary goods and services. To provide and assist others in providing abortion services, health care providers engage in interstate commerce to obtain and provide training. To provide abortion services, health care providers employ and obtain commercial services from doctors, nurses, and other personnel who engage in interstate commerce and travel across State lines.

The same sort of capacious Commerce Clause reasoning, of course, also could justify national restrictions on abortion, as in the case of the Partial-Abortion Ban Act. Since Democrats take it for granted that Congress has the authority to legislate in this area, they are opening the door to federal policies they would abhor, contingent on which party happens to control the legislative and executive branches.

Marjorie Dannenfelser, president of Susan B. Anthony Pro-Life America, said she was “deeply disappointed” by Trump’s unilateral repudiation of a national solution to the abortion issue. That position, she complained, “cedes the national debate to the Democrats who are working relentlessly to enact legislation mandating abortion throughout all nine months of pregnancy.” If they are successful, she warned, “they will wipe out states’ rights.”

But the same could be said of Republicans who are determined to impose a national abortion ban, and Trump’s rejection of that approach reinforces his argument that he is a moderate compared to Biden and other Democrats. “It must be remembered that the Democrats are the radical ones on this [issue],” he says in the Truth Social video, “because they support abortion up to and even beyond the ninth month.” He wants voters to know he is repelled by “the concept of having an abortion in the later months and even execution after birth.”

Leaving aside Trump’s dubious claim that Democrats favor infanticide, there is a kernel of truth to his gloss. According to Gallup, 60 percent of Democrats say abortion should be “legal under any circumstances.” And under Blumenthal’s bill, states would have been barred from banning abortion even after viability “when, in the good-faith medical judgment of the treating health care provider, continuation of the pregnancy would pose a risk to the pregnant patient’s life or health.” That is a vague and potentially broad exception, especially if “health” is read to cover mental as well as physical health.

At the same time, Trump’s focus on late-term abortions elides the reality of when the procedure is typically performed. According to the CDC’s data, more than 80 percent of abortions are performed prior to the 10th week, while just 4 percent are performed at 16 weeks or later. Trump’s emphasis on “abortion up to and even beyond the ninth month” (whatever that might mean) also obscures the extent to which he disagrees with voters who favor bans that cover most or nearly all abortions. But it aligns him with the views expressed by most Americans, who generally favor some restrictions while opposing a complete ban.

The post Embracing a Federalist Approach to Abortion, Trump Condemns Democrats As ‘Radical’ appeared first on Reason.com.