This story originally was published by Real Clear Wire

By Delaney Duff

Real Clear Wire

Google’s difficulty in mitigating bias from their artificial intelligence systems – even after explicitly going to great lengths to minimize bias – spells trouble for the Department of Defense. Bias can cause AI tools to irrevocably malfunction and derail AI development. Google recently paused Gemini, their largest and most capable AI model, from generating images after it created historically inaccurate and offensive images of people. Google explained that their attempts to design a less biased, more inclusive image generation tool caused the model to malfunction instead.

This is especially concerning as the Defense Department plans to leverage AI at scale, including for training simulations, intelligence analysis, recruiting personnel, translating documents, drafting policy, and even powering autonomous weapons. If the U.S. continues to prioritize the speed of AI development over safety, biased AI systems will ultimately slow the adoption rate, ceding the country’s technical edge to China.

Biased AI systems are ultimately dangerous. They make mistakes or generate inaccurate assessments leading to poor decision making or even system failures that harm people. Unanticipated AI failures could cause problems ranging from erroneous intelligence reporting to inaccurate targeting.

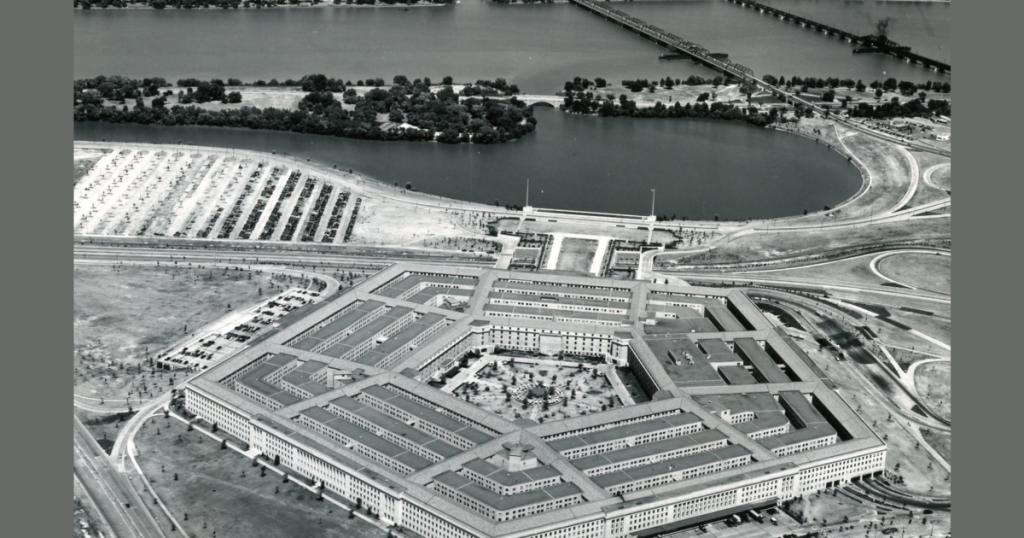

In the Defense Department, the Chief Digital and Artificial Intelligence Office (CDAO) is tasked with accelerating the adoption of artificial intelligence technologies across the national security ecosystem. CDAO’s Responsible AI team is tackling the problem of biased AI models by instituting a “bias bounty” program, which recruits the public to identify instances of bias in its large language models, starting with chat bots, in exchange for a cash prize.

By identifying bias in generative AI tools, the Pentagon hopes to understand the benefits and risks posed by these systems in order to implement safeguards. Mitigating the risks is crucial as the U.S. increasingly relies on AI development to provide warfighters with a competitive edge over its adversaries.

Relying on infrequent, small-scale public participation programs for identifying AI bias is inadequate because it assumes bias is easily detectable and does not account for the way biased outputs morph overtime, even after developers implement “fixes.” Biased AI systems disproportionately disadvantage certain groups especially when AI model training data is under representative of reality or already reflect existing biases.

Even more concerning are failures in AI-powered weapons targeting. AI systems could inadvertently select targets that violate rules of engagement such as women and children noncombatants. Recent reports accuse two IDF artificial intelligence targeting systems of increasing civilian casualties in Gaza by purposefully targeting Hamas operatives at home and erroneously identifying individuals as militants even when they had no or very tenuous links to these groups.

Policymakers, military officials, and private industry increasingly frame AI development as an arms race with China because Beijing hopes to leverage AI to enhance its power and gain a strategic advantage over the U.S. and its allies. Substantial ethical issues and discrimination as a result of AI bias should be enough to give lawmakers pause.

Overfocus on development speed sidelines real concerns over AI safety. Holding AI to high ethical standards is not an impediment to progress. Rather, it ensures greater system success that is essential for broad trust and adoption.

Removing bias requires more than technical solutions alone. In addition to periodic bias testing to ensure the models are operating properly, the Defense Department should provide and expedite clearances for data scientists and others involved in training AI models, so they have access to larger portions of datasets. Greater access allows those most knowledgeable about AI systems to spot instances where the model is producing biased outputs and correct mistakes more easily.

Operators of these tools should receive more extensive training programs that include instruction on identifying biased outputs enshrining the practice of not blindly trusting the system results. These tools are not perfect, and operators must know when and how to question or override a decision suggested by AI. The DoD should mandate their developers follow CDAO’s Responsible AI Toolkit that aligns with the DoD’s AI Ethical Principles and continuously evaluate and update the framework to keep pace with rapid technological advancement.

Finally, the U.S. should invest greater funding into STEM programs for underrepresented groups and communities. Only 26% of people in computing are women, and women only make up 18% of researchers at lead AI conferences. Representation for people of color is even worse, with less than 7% of employees at lead technology companies being Black or Hispanic. Greater access to STEM education creates a more diverse workforce and this diversity is essential for creating less biased AI systems. These new perspectives disrupt organizational group think and echo chambers, foster creative problem solving, and promote innovation.

Short-sighted focus on AI development speed over safety could spell disaster for the Defense Department. If the United States hopes to shape the future of the 21st century, it must make minimizing AI bias a top priority.

Delaney Duff is a Fellow at the Pallas Foundation for National Security Leadership whose mission is to to foster the education and professional development of emerging leaders from traditionally under-represented groups in global and national security. She is a master’s student in the security studies program at Georgetown University.

The post Defense Department’s Efforts To Combat AI Bias Don’t Go Far Enough appeared first on The Gateway Pundit.