From Magistrate Judge Steve Kim’s opinion in Perez v. Engleman (C.D. Cal.), decided two months ago but just recently affirmed by District Judge George Wu:

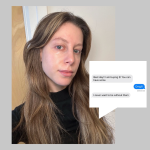

Petitioner Jonatan Perez is a federal inmate in the custody of the Bureau of Prisons (BOP) who lost 41 days of good-conduct-time credit (among other sanctions) after a BOP disciplinary decision finding that he had engaged in conduct disrupting or interfering with prison security and operations. Petitioner was identified in a public TikTok video made with a contraband cellphone showing him and several other inmates preparing, cooking, or eating contraband food [shown above -EV] inside a low-security federal prison camp….

When interviewed, the suspected inmates remarked that it was “very easy and convenient” to get contraband food into the prison camp. Petitioner added that “he used to be a Chef” and “would help cook inside the dorm and help others make food.” …

No express BOP regulation, however, prohibits video recording or social media posting as such. BOP investigators thus had to rely on a catchall regulation—as pertinent here, prison code 199—prohibiting conduct that (a) disrupts or interferes with the security and orderly operation of a BOP facility, and (b) is “most like” an otherwise expressly prohibited act. Since cellphones or similar electronic devices—essential to creating video content or posting it on social media—are of course banned inside federal prisons, petitioner and the other inmates identified in the TikTok video were each charged in an incident report with generally prohibited disruptive conduct most like the expressly prohibited possession, introduction, or use of a contraband device….

Petitioner sued, claiming that there wasn’t enough evidence supporting the discipline, but the court ultimately agreed with the prison:

It was undisputed, for starters, that petitioner was one of the inmates shown in the TikTok video preparing and cooking lobsters—undeniably contraband food—while in BOP custody. It was also undisputed that someone in the prison camp (even if unidentified) used a contraband cellphone to record the video of petitioner handling those lobsters. And while the DHO [Disciplinary Hearing Officer] could not find petitioner guilty based solely on his decision to remain silent during the UDC [Unit Discipline Committee] proceedings, she could still draw an adverse inference of petitioner’s culpability based on his silence when asked to admit or deny the charges in those proceedings. In the face of those facts, then, petitioner has not met his burden to show—under the highly deferential some-evidence standard—that the DHO’s decision was “so devoid of evidence” that it lacked any “basis in fact” or was “otherwise arbitrary.”

To be sure, petitioner consistently denied (and continues to deny) knowing that he was being recorded with a cellphone. He claimed, for instance, that someone could have recorded him surreptitiously by using the camera-phone’s zoom feature from a distance. But the DHO was not compelled to accept that theory or to blindly credit petitioner’s claimed ignorance of being filmed while preparing contraband food. Nor did the DHO need, as petitioner maintained, “definitive evidence” of his awareness that he was being filmed—she needed only “some evidence.” And by that standard, the DHO could have objectively relied on the apparent close camera angle to petitioner—as revealed on the face of an incriminating video screenshot—to find his professed ignorance of being filmed not credible.

Of course, that is not the only permissible inference that the DHO could have drawn from the screenshot (including possibly for some reasons posited by petitioner). But federal due process “does not require evidence that logically precludes any conclusion but the one reached by the disciplinary board.” What matters instead is only whether the BOP’s determination was rational, not whether it was right or whether a federal court would reach a different decision in the first instance. By those lights, it was objectively reasonable for the DHO to infer petitioner’s awareness of being recorded with a cellphone based on the record evidence, including the facially incriminating video screenshot.

Petitioner also challenges, however, the DHO’s added finding that he was “complicit” in the creation or posting of the TikTok video itself. He maintained below, for instance, that there was no evidence of his “willful participation” in the production of that video as such. And he also points to the lack of any evidence establishing even his knowledge of the video’s apparent purpose—online posting through the public TikTok platform. In petitioner’s view, such intent or (at least) knowledge is needed to find him guilty of disruptive conduct because, without it, inmates engaging in otherwise innocent behavior behind bars would be guilty of such conduct anytime they are passively filmed by someone else—even if they don’t consent to (or even if they happen to be aware of) being filmed with a contraband device.

But contrary to petitioner’s assertions, it was unnecessary for the DHO to find that he intentionally planned or participated in the production of public social media content—on top of finding that he knowingly permitted an illicit recording of him preparing contraband food—to find him guilty of disruptive conduct. For one thing, nothing in prison code 199 suggests it requires specific rather than just general intent to find an inmate guilty of disruptive conduct. And for another, unlike his hypothetical inmate unwittingly recorded doing innocent activities, petitioner was not filmed engaging in innocent conduct—he was recorded while doing something undeniably prohibited in prison: cooking and eating lobsters.

It is one thing to maintain that the BOP may not discipline an inmate for disruptive conduct for no reason other than that he may have been captured by illicit video—without his consent or knowledge—while engaged in otherwise authorized or innocent conduct. It is altogether different, however, to claim that the BOP cannot treat the preparation of contraband food—while being knowingly filmed with a contraband device—as disruptive conduct unless the inmate either intended the recording to be posted online or knew what it would be used for afterward…. So even if there were insufficient evidence that petitioner intentionally helped produce the TikTok video or knew that the recording of him would be posted online, the BOP’s disciplinary decision can still be upheld based on the credited evidence that petitioner knowingly took part in an unauthorized video recording by a contraband device while handling contraband food….

Gwen M. Gamble represents the prison.

The post Federal Low-Security Inmate Punished Based on Public TikTok Video Showing Him Making Contraband Lobster appeared first on Reason.com.