Here’s what people who weren’t there don’t know about the moment the dot-com bubble burst: there was no single moment.

The date was different for everyone, and the range varies a lot more than you think. So far as I was concerned, the dot-com economy crashed on the morning of January 11, 2000. That’s when I entered the Time-Life building, seething because the Time Warner CEO had just sold our company to AOL, of all internet hellholes, for $183 billion. Just keep your head down, I thought in the elevator, and maybe you won’t be asked to cover a deal that insanely overvalues a company you just called “training wheels for the internet.”

As I crept into the morning meeting, a voice boomed: “Chris! Let me introduce you to the men you’ll be covering this week,” said Time magazine editor Walter Isaacson, presenting AOL CEO Steve Case and Time Warner CEO Jerry Levin. Cue forced smiles and clammy handshakes all around.

The vibe shift of the dot-com bubble began in … January 2000?

The history of financial bubbles, from the South Sea original that suckered in Sir Isaac Newton to the AI implosion of 2024 where a lot of the smartest people in tech seem set to lose their shirts, can be summarized thus: it’s all about vibes, man.

Fans of a new technology or financial scheme get so caught up in the potential for exponential profits, they shun nuance and caveats and risk. Irrational exuberance, as we started saying in the 1990s. Stock prices go through the roof, hordes of new investors stampede in. But nuance and caveats and risk are stubborn things, and there’s always a moment where society at large starts to see through the illusion: a vibe shift, basically, like the one we’re living through now.

Looking back on the decline of the dot-coms, something I witnessed up close in San Francisco and Silicon Valley from March 2000 onwards, two things strike me. First of all, the process was far slower than I thought; we were still very much living in true believer dot-com land for a time in 2001, with all the dumb business models and high-budget launch parties that implied. (Picture a lot of ice sculptures with slow-melting corporate logos; many of these startups were immune to irony.)

So it was less a bubble, more a balloon slowly leaking. And here’s the second thing I find striking looking back at my diaries of the time: the balloon really seems like it started leaking a lot earlier than March 2000. That’s when histories of this quintessential tech collapse place the vibe shift, which makes sense: The NASDAQ, that much-watched index of all things tech, hit its high water mark of 5,084 on March 10, 2000. It would not blast past that number again for 15 years.

But in the first two weeks of the year, a couple of events (or non-events) made the tech world seem like a paper tiger in the eyes of many. The year began with a profound sense of relief that the so-called Y2K millennium bug, where legacy software couldn’t tell the difference between 1900 and 2000, hadn’t produced the predicted global computer meltdown. But relief soon curdled into irrational anger: had all the techies just hyped up the threat in order to bilk us for unnecessary code rewrites? What else could they be lying about?

Credit: Allan Tannenbaum/Getty Images

Then came one of the most topsy-turvy deals in history. On January 10, the AOL-Time Warner deal was announced. But one factor kept getting downplayed in the press, especially by my employers: given that AOL would end up with 55 percent of the resulting company, it was a takeover.

“I almost had to check that it wasn’t April 1,” I wrote in my diary that day. “It sounded like a bad joke.” After AOL CEO Steve Case walked into that Time magazine morning meeting to meet some of his new employees, I had to board a plane for Dulles and interview Case’s lieutenants about all the celebrating that had gone on in AOL HQ. None of them could stop grinning at what this CD-pushing internet service provider had just achieved.

But investors weren’t grinning. AOL stock slid on the news. There was something instinctively wrong about this deal. All well and good when the dot-coms were getting eye-popping valuations based on no profits now or potentially ever, but now they’re going to leverage them to buy old-school giants who actually make a profit? It was the tail wagging the dog, and it clearly couldn’t last.

Spoiler alert: the company has been broken up and sold off since then, most of it to AT&T. Time magazine was eventually sold to Marc Benioff, founder of Salesforce, who in 2000 was obsessed with promoting his company by sending me and other San Francisco journalists packages full of … chocolate, for some reason.

We saw the crash coming

More than a year ahead of March 2000, you could already find voices in the media who knew what the sky-high valuations signaled. “This is a real bubble and it’s going to pop,” one tech analyst told Kiplinger’s, a financial magazine, in November 1998. “A bit of the air leaked out of what many Wall Street pros call the internet bubble,” the New York Times reported in January 1999, quoting a Morgan Stanley analyst: “I promise you, like all bubbles, this bubble will come to a very bad end.”

Nobody had cared then. After Y2K and AOL-Time Warner, they started to care. My diary for January 25, 2000, the day my predecessor as San Francisco bureau chief quit to join a dot-com, reveals the mood of the time. “What the site does, I’m still not exactly sure,” I wrote. The dot-com-bound journalist had already pitched me, with a line I now imagine being read in the voice of Kendall Roy: “I mean, internet telephony is a dark horse for story of the year. You should totally write about it.”

The startup’s exact business model, I concluded, “seems less important than the fact that it just got $60 million in VC funding. Who out there cares what most of this dizzying parade of dot-coms do anyway? They make money for papa on IPO day, that’s what.” Except that particular IPO never happened. Fast forward to 2024, and the site in question advertises itself as “the premier destination for psychic readings by phone or online chat.”

(For what it’s worth, Morgan Stanley, now a little more irrationally exuberant than it was back in 1999, recently predicted 10 to 15 AI IPOs this year. Whether there’s any actual wiggle room left for AI company IPOs in a suddenly unfriendly 2024 landscape, however, remains to be seen.)

Microsoft made the dot-com bust official. But why?

Something else happened in January 2000 that made people uneasy about the tech world: On January 13, the world’s richest man handed over the keys of the world’s biggest tech company to a guy who would later become famous for dancing like a monkey.

Bill Gates’ Microsoft, of course, was the 800-pound gorilla of the time. I’d been covering the company’s trial, on antitrust charges, since 1998. It had clearly been stifling innovation in the early internet space, using its Windows desktop dominance as leverage.

“If Microsoft is a monopoly, should we risk angering it?” was one typically weird question I was asked in my first official AOL chat from San Francisco, a kind of proto Reddit AMA, on April 3, 2000.

That was the day U.S. Judge Thomas Penfield Jackson delivered his judgment: Microsoft had violated the Sherman antitrust act. Breaking up the company, as had been done with AT&T in the 1980s, was on the cards. The market sent Microsoft stock tumbling 15 percent in a single day.

It made no sense that this event would be the starting gun for a run on dot-com stocks. If anything, a less powerful Microsoft would allow more upstart tech companies to flourish. But sense, as we’ve already established, has nothing to do with tech bubbles.

Together with news that the SEC was quietly cracking down on shady dot-com accounting practices, it suddenly felt like “the cops have finally burst in” on Silicon Valley’s party, as Bloomberg wrote at the time. The vibe shift began with AOL Time Warner; as of April it was starting to feel irreversible.

The dot-com bubble took its sweet time deflating.

Even after the Microsoft decision, contemporary reports — and investors — were surprisingly tentative.

“Is the dot-com bubble ready to burst?” wondered the San Francisco Examiner on April 5, 2000. In July, the Palm Beach Post quoted an investor who was “not worried about the dot-com bubble bursting.” By September, tech pundits generally agreed a dot-com meltdown had happened, but like Bill Gates, didn’t think this meant the technology sector as a whole was in a downturn.

Here’s the thing about market peaks; you don’t see them until they’re far in the rearview. In the case of the dot-com market, there were upswings in the meantime. Look at the NASDAQ chart for 2000, and you’re not seeing a 1929-style crash. You’ll note two giant spikes after March, moments in the summer and fall when the tech index seemed to be heading back to 5000 again. The NASDAQ would not hit its post-bubble low until October 2002.

Credit: Wikimedia

In Silicon Valley, not much felt like it had changed. The IPO market may have cooled, but wasn’t expected to stop completely. When I interviewed Larry Page and Sergey Brin for the first Time story on Google in the fall of 2000, I asked how it felt knowing they’d be billionaires soon. (In the end, Google would wait another 5 years before conditions were right for a public offering.)

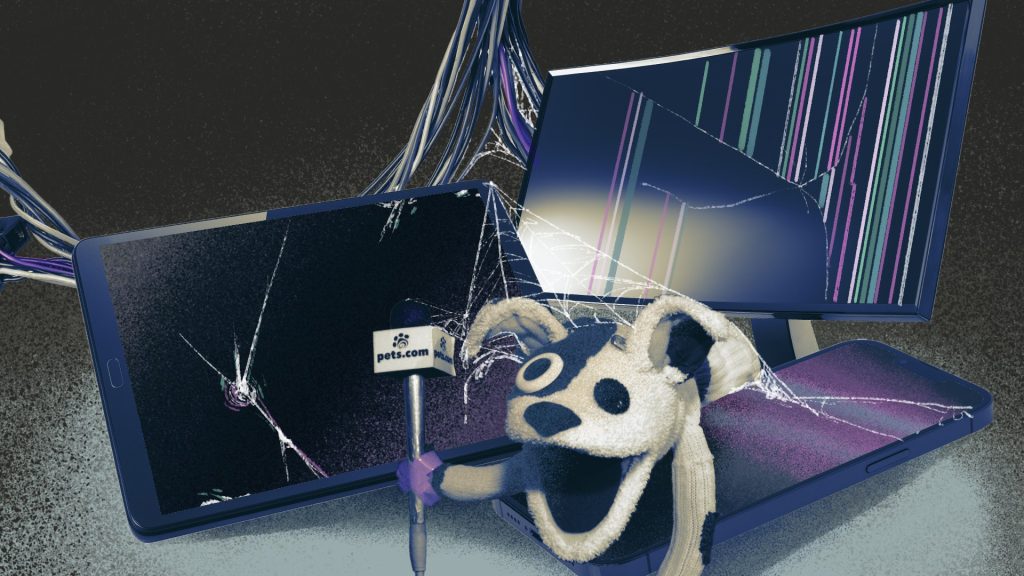

The most iconic dot-com hot messes clung on for much longer than we remember. Pets.com didn’t bite the dust until November 2000 — and that dog puppet of theirs was still making appearances at events in 2002. I’d been using Kozmo.com, a much-mocked Postmates-style service with no delivery fee, to bring me Krispy Kremes and DVDs in New York in December 1999; I was still using it in San Francisco as late as February 2001. Kozmo shut down 2 months later, which turned out to be very good news for my burgeoning waistline.

If the bubble burst in 2000, someone had forgotten to tell the fat-walleted engineers raising everyone’s rents. In mid-2000, I reported on a protest by residents of the Mission, San Francisco’s historically Hispanic neighborhood, against dot-com employees moving in. A card game called Burn Rate, where players took on the roles of dot-com CEOs weighed down with massive overheads, was all the rage in the city that year.

But it wasn’t until 2001 that tech layoffs became a deluge. That was the year I wrote story after story with headlines like “It’s grim and dim for the dot-coms” (that one was about companies coping with layoffs and the statewide “brownouts” brought on by California’s reliance on the energy scalpers at Enron.)

As AOL Time Warner’s own layoffs began to bite, demand for dot-com schadenfreude was never higher. In the second week of September, I was assigned to talk to former dot-com employees for a cover story with the tentative title “living happily with less.” The day I had assembled them for dinner, the biggest news of the century broke. Dinner was canceled, and I was never asked to write a dot-com story again.

Tech rebounded faster than expected.

After the all-consuming catastrophe of 9/11, attention for tech news was in short supply. And that, ironically, was when the tech world got really interesting.

In October 2001, Steve Jobs handed me and other journalists the first generation iPod. But the tech world’s stock was so low in New York, I had to fight for a single page in Time on the MP3 player that seemed so clearly like a game-changer — especially once I saw how fast my parents figured out how to use it.

That was the story of tech in 2001: without so much dot-com froth in the way, the future suddenly became much clearer.

The Google guys kept talking about a groundbreaking product, not yet called AdSense, and how it would actually extract that much-promised revenue from the internet. I wrote about Reed Hastings, a former AI researcher who’d quit in frustration at the slow pace of his chosen field. His company Netflix and its DVD-by-mail product seemed promising (I didn’t focus so much on the long-term “deliver movies over the internet” plan; been there, heard that). Jeff Bezos, whom I’d pitched as Person of the Year two years prior, spent a day in Seattle trying to convince me that Amazon’s business model would work in the long run.

Apple, Google, Amazon, and Netflix? All 2001 needed to complete the future lineup of the five tech giants was a programming prodigy who was then still in boarding school. Only in 2002 would he arrive at Harvard, where inspiration waited in the form of a dorm room face book.

“History doesn’t repeat itself, but it often rhymes” — so wrote another San Francisco journalist, one who repeatedly lost his shirt on startups, at the turn of a previous century. History isn’t exactly about to repeat itself with the 2024 correction. But we can at least hope that the final line of this dot-com-AI stanza — the one where the strongest companies emerge, battle-hardened and ready to launch new revolutions — will be a couplet for the ages.