I recently posted a long critique of the Fifth Circuit’s ruling last week in United States v. Jamarr Smith, and specifically the court’s ruling that Google’s geolocation database is too big to search with a search warrant. It remains to be seen what might happen with the case. Just today, DOJ filed an unopposed motion asking for 60 days to file a petition for rehearing. Also, the court has withheld issuance of the mandate on the request of at least one judge.

With that pending, I’m delighted to feature a debate of sorts over the merits of the ruling. Jennifer Granick and Brett Max Kaufman, lawyers for the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) who are both very active litigating in this area, wrote to me today with an ACLU response defending the Fifth Circuit’s ruling and asking if I might publish it here at the Volokh Conspiracy. Jennifer and Brett are both outstanding lawyers, and I’m delighted to host a debate on this question. With their permission, I am posting their response to my post, followed by my reply below that.

Here is their response, published in full:

The Fifth Circuit’s Supposedly “Bananas” Ruling that Geofence Searches are Unconstitutional Is Correct

Jennifer S. Granick & Brett Max Kaufman, American Civil Liberties Union

Last week, the federal Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals issued a unanimous opinion that “geofence warrants”—which sweep through hundreds of millions of account holders’ location data in the hopes of ensnaring people who are estimated to have been near the scene of a crime—violate the Fourth Amendment. In a blog post on this site, Orin Kerr criticized the court’s holding as “bananas.” But if this kind of ruling is bananas, we’ll happily take more of them by the bunch.

The Fifth Circuit’s decision, in a case titled United States v. Smith, is a reasonable response to the Golden Age of Surveillance ushered in by companies’ unprecedented capture of previously ephemeral and unknowable facts about us. The Fifth Circuit held that police may not trawl through a database of hundreds of millions of people’s sensitive location histories in the hopes that they will be able to find people who were, according to Google’s computers, in the vicinity of a crime at some point in the past. The government uses this technique, geofence searching, with increasing frequency. It pulls out of the cloud people whose phones are estimated to have been near the scene of a crime—even if the person was actually somewhere else. It looks not just for suspects, but also witnesses, ensnaring a subset of individuals destined for further law enforcement scrutiny.

The Fifth Circuit held that such an overbroad search is akin to the kinds of “general warrants” that the Fourth Amendment was intended to prohibit. As a result, no warrant can make this novel surveillance technique legal.

Considering the analog equivalents of this kind of dragnet helps explain why: For example, police might know that some bank customers store stolen jewelry in safe deposit boxes. If they have probable cause, police can get a warrant to look in a particular suspect’s box. But they cannot get a warrant to look in all the boxes—that would be a grossly overbroad search, impacting the privacy rights of many people as to whom there is no probable cause. (In one recent case, the government actually tried something similar, but the Ninth Circuit rejected the attempt.)

Likewise, police might know that some people sell drugs out of their homes in a certain neighborhood. If they have a target (whether an address or a person), they can get a warrant to search a house. But they may not search all the homes in the neighborhood based only on the knowledge that illegal drugs were sold in the area.

Kerr raises four main objections to the court’s reasoning in Smith.

First, Kerr says that Smith is inconsistent with United States v. Karo, a 1980s case in which the Supreme Court held that law enforcement needed to get a warrant to track a radio-tracking beeper, which the government had placed inside a can of chemicals to be picked up by a suspect, into a private area like a home or locker. The government contended that that it needn’t get any warrant at all to conduct this kind of surveillance, because the Fourth Amendment’s particularity requirement was a poor fit for a situation in which police could never name in advance where the beeper might go. The Supreme Court swatted away that argument by explaining that it was sufficient for particularity purposes to specify the “object into which the beeper is to be placed, the circumstances that led agents to wish to install the beeper, and the length of time for which beeper surveillance is requested.”

If police can get a warrant for that kind of tracking, Kerr suggests, surely they can get one for geofence searches, too. The Karo Court, he says, rejected an argument that beeper searches could never meet the particularity requirement—and that rejection should apply to geofence searches, too.

But the argument Karo rejected was the government’s, and it was aimed at persuading the Court that particularity requirement was such a bad fit that the Fourth Amendment shouldn’t regulate its beeper surveillance at all. Rather than permit unsupervised, warrantless beeper surveillance, the Court “articulated a way to draft warrants to allow the surveillance.” But that is far cry from the argument the Fifth Circuit was evaluating in Smith—an argument from the defendants that geofence searches are so broadly invasive that they are akin to the long-reviled general searches banned by the Fourth Amendment entirely.

Not even the government, in its opposition brief on appeal, thought Karo was relevant enough to the geofence warrant issue to cite it even once.

Karo‘s facts are not analogous to geofence searches. While the final destination of a beeper tracker is unknown, police are tracking a particular object in real time. The government has possession of the object and installs a beeper. Only a few people subsequently will take possession of the object and it will only travel to a few places, as the police follow it. The police know what the object is, why it is relevant to the crime under investigation, who is likely to take possession of it, and for what criminal purpose.

But the Google location history database at issue in Smith contains location data from “592 million individual accounts”. With geofence searches, all the police know is that a crime took place in the past, and where. Google’s location history database is entirely comprised of constitutionally protected intimate location information, enabling comprehensive and retroactive surveillance of hundreds of millions of people. When the government searches the location database, it is searching through all of that information, after the fact. The people affected are all the people in the database, not just those whose information is a potential match.

Further, what the government learns is much more extensive than the location of a Karo-style beeper. When conducting a geofence search, the government doesn’t even know whether the suspect’s data will actually be found in the database—not that the government cares, since they are often not only looking for suspects, but for witnesses, too. The search will almost certainly rope in people who were not near the crime or merely passing by, due to the imprecision of some of the location data that Google collects. The government obtains information potentially revealing personal activities, habits, and associations about any number of people—suspicious or not. The breadth and technology involved in geofence-type database searches make them a whole new ballgame, worlds away from planting and tracking a beeper placed in a can of chemicals intended for use in drug trafficking.

Second, Kerr maintains that that the Fifth Circuit opinion clashes with United States v. Carpenter. In Carpenter, the Supreme Court held that police need a warrant to seek an identified suspect’s cell phone location history. Of course, like geofence data, cell phone location data resides in a company’s giant database. Kerr takes this to mean that any search through a massive database of location data must be permissible with a warrant. But there is very little in common between the targeted query pulling up one suspect’s records in Carpenter, and the dragnet search for anyone whose phone was in or near a 24-acre area in Smith. Police can ask an email provider to turn over a particular person’s messages with a valid warrant, but that doesn’t mean police can direct the company to search through every email of every user in the hope of finding someone who was discussing a crime. And of course Carpenter did not address, let alone reject, a general warrant argument like the one at issue in Smith. To the contrary, the Court took pains to remind us that “The Founding generation crafted the Fourth Amendment as a response to the reviled ‘general warrants’ and ‘writs of assistance’ of the colonial era, which allowed British officers to rummage through homes in an unrestrained search for evidence of criminal activity.”

Third, Kerr argues that whether the identity of a suspect is known at the time of a search is constitutionally irrelevant. That is generally true—some valid warrants are of course intended to gather evidence to identify a suspect. But that doesn’t mean that all such searches are constitutional. In each of the hypothetical examples Kerr gives, there is a target—an account controlled by an unknown user.

In any case, the lack of a known suspect in a particular case is not what the Fifth Circuit complained about. Rather, the Fifth Circuit was describing the geofence search technique itself as an inherently suspicionless dragnet where police never have a target:

In other words, law enforcement cannot obtain its requested location data unless Google searches through the entirety of its Sensorvault—all 592 million individual accounts—for all of their locations at a given point in time. Moreover, this search is occurring while law enforcement officials have no idea who they are looking for, or whether the search will even turn up a result. Indeed, the quintessential problem with these warrants is that they never include a specific user to be identified, only a temporal and geographic location where any given user may turn up post-search.

That observation seems plainly correct to us.

Fourth, Kerr’s last point is that the Smith decision may have implications for surveillance conducted by national security agencies, which regularly search through gigantic repositories and streams of data that include the private information of Americans. He predicts that we will soon read in the paper that the opinion has interfered with some presumably worthwhile national security surveillance program as a roomful of very worried national security lawyers, presumably with furrowed brows, struggle to figure out how to comply.

We have a prediction, too. We may see an unnamed national security official cited in a news story, lamenting the possible interruption to some purportedly essential surveillance program because of Smith. No one will tell us what the program supposedly is, or how exactly some limitations on the ability of law enforcement to search huge databases of private information without individualized suspicion interferes with the nation’s security, but that is what the anonymous source will suggest.

Don’t believe it. National security lawyers excel at exploiting legal loopholes to justify secret programs and insulate them from judicial scrutiny. We find it extraordinarily hard to believe that they will read the Fifth Circuit’s opinion in an unnecessarily overbroad and self-defeating fashion to require the executive branch to shut down one of its ongoing national security surveillance programs. Instead, as they usually do, the lawyers will find a way to justify the program to themselves, even if only by saying that the Fourth Amendment applies differently to foreign intelligence surveillance than to criminal investigations. Nonetheless, advocates of Big Surveillance will still repeat the leaked, manufactured concern about national security to ensure it hangs over courts’ future efforts to consider and apply constitutional protections to the hundreds of millions of individuals whose private lives are exhaustively documented in ones and zeros in gigantic corporate for-profit databases.

When it comes to national security surveillance, the government’s litigation tactics are designed to prevent courts from reaching incredibly important Fourth Amendment questions, like the one in Smith, on the merits. In criminal cases, for example, the government has a long track record of improperly withholding notice of foreign intelligence surveillance from defendants. In civil challenges to national security surveillance, the government has aggressively relied on the standing and state secrets doctrines to seek dismissal at the earliest stages of litigation.

Following the Supreme Court’s lead in cases like Riley and Carpenter, courts around the country have been striving to adapt constitutional privacy protections to novel surveillance enabled by advanced digital technologies. Things like conversations, reading, and travel used to be ephemeral, and were not recorded, and all-access has never been the rule. But now, law enforcement feels entitled to access all these new repositories of private information however it can. While it may be the job of government lawyers to push for access, it’s the role of the Constitution and the courts to push back. That’s what we see the Fifth Circuit doing in Smith.

Thanks very much to Jennifer Granick & Brett Max Kaufman for their response on these issues. Here’s my reply, taking the order of the four points I made in my initial post. (Because the reply to me was written in the authors’ official capacities as ACLU attorneys, I will respond to them a bit formally as “the ACLU,” instead to Jennifer and Brett.)

(1) On the Importance of United States v. Karo

First, the ACLU notes that the government did not raise Karo in its brief:

Not even the government, in its opposition brief on appeal, thought Karo was relevant enough to the geofence warrant issue to cite it even once.

It’s true that the government doesn’t cite Karo. But that brings up a very interesting aspect of the litigation more broadly: Reviewing the briefs filed in the case, I don’t think either side really briefed the question that the panel ruled on—whether the Google file was too big to be searched. Reading the defendant’s initial brief, the statement of issues announces that it will argue that geofence warrants are unconstitutional categorically (p.2). But the brief never actually develops that argument, as far as I can tell. It states the argument at the. top of page 35, and hints at it in footnote 8. But it mostly argues other issues, such as that this particular geofence warrant was too broad. The reply brief is similar. It alludes to such an argument in passing (p.4), but it doesn’t make it. No amicus briefs were filed in the case, either. From what I can tell, there was no serious briefing on the warrant issue that was resolved by the Fifth Circuit’s opinion.

Indeed, after now listening to the oral argument, I don’t think I hear the argument being made by Smith’s counsel there, either. At about the 8-minute mark, Judge Ho asks defense counsel to say specifically why this was a general warrant. Smith’s counsel does not respond that this was a general warrant because the Sensorvault database was too big, Instead, counsel makes a different argument, that the warrant sought too much data to be seized and handed over to much the government.

I should be clear that the issue of Sensorvault being too large to be searched does get discussed during the oral argument. Judge Ho raises and presses this claim during the questioning of the government, starting at about the 17:45 minute mark. And at the 23 minute mark, Judge Ho describes that claim as what, in his words, “I think” is the argument defense counsel is making. But unless I’m missing it, that’s the first time it is discussed, at least more than in passing. In the rebuttal, defense counsel again focuses on the scope of what the government was looking for, not raising the size of Sensorvault or argues that the file was too large to search. As far as I can tell, the only time defense counsel talks about that is in the last minute of the argument, when Judge Ho asks counsel to respond to the government’s responses to Judge Ho’s earlier questions on that.

So it’s true that the government did not cite Karo. But Karo is important as a response to a “no warrant can be issued” argument, and that’s not an argument that appears to have seriously briefed by either of the litigants.

Back to the ACLU post.

ACLU next argues that Karo is distinguishable. The key difference, the ACLU claims, is that the geofence warrant can yield a lot more personal information than the tracking beeper did in Karo. Assuming this is true, though, I don’t know how it’s relevant to whether a warrant can be obtained. The arguments the ACLU is making are arguments about why the data should be protected under the Fourth Amendment in the first place. Assuming the panel was correct on that, those points are justifications to require a warrant, not a reason to refuse to allow a warrant.

But what about the idea that the search here is just too invasive? It seems important to note that warrant clause does not impose a general requirement that searches be narrow. As Justice Scalia stressed for the Supreme Court (overturning 9-0 a Judge Reinhardt decision from the Ninth Circuit) in United States v. Grubbs, particularity requires two specific things:

The Fourth Amendment, however, does not set forth some general “particularity requirement.” It specifies only two matters that must be “particularly describ[ed]” in the warrant: “the place to be searched” and “the persons or things to be seized.” We have previously rejected efforts to expand the scope of this provision to embrace unenumerated matters.

That posed a big problem in Karo, because there really was no known “place” where the search was occurring. But in this case, everyone knows that the warrant is being sent to Google, and that it is conducting the search there, albeit of a particular very large database. So if anything, I would think the place problem was greater in Karo than it was here.

(2) Comparisons to Email Searches and the Relevance of Carpenter

The ACLU also argues that searching through Sensorvault is very different from a traditional kind of Internet warrant search, such as for an individual email account. They write:

Police can ask an email provider to turn over a particular person’s messages with a valid warrant, but that doesn’t mean police can direct the company to search through every email of every user in the hope of finding someone who was discussing a crime.

This mixes apples and oranges, it seems to me. It treats an argument about the place to be searched (the database) as if it were an argument about the things to be seized (any discussions of a crime). Here’s the more relevant question: If an email provider set up all of its emails in a single database, with the different emails together, could it search for the emails of a particular account holder?

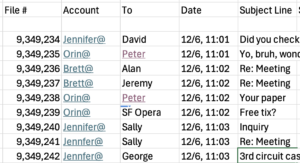

Let’s think this through. Imagine a provider that has all of its emails of all of its customers in a single huge database file containing emails from all users. Let’s say there are one million customers, with a billion emails total stored in that one database. Here’s a made-up snapshot, below, of part of what the file might look like, showing you just part of a few of the billion entries in the database. The left column is the file number, from one to a billion. The next column is the account name, next the to address, then the date, then the subject line. Imagine other columns to the right, just out of view, with main text, attachments, and the like:

Imagine the government came to the provider with a warrant for emails in Orin’s inbox that were delivered on December 6th between 11:01 and 11:03. Because all of the provider’s emails are in a single massive database file, the provider would get those specific Orin emails by doing a search through the entire file of one billion emails for those matching the query Account=”Orin@” and Date=”12/6 at 11:01 to 11:03″.

Is that a particular warrant that satisfies the Fourth Amendment? I would think so. But under the Fifth Circuit’s reasoning—reasoning that I gather the ACLU agrees with—I think that would be an illegal general warrant, as it would mean searching through a million people’s emails for those responsive files. Think about it: It’s like rummaging through one million homes, the argument would run, with an entire city’s worth of private virtual homes being scanned through and closely scrutinized by powerful supercomputers for a match with the relevant criteria— the specific account name (Orin) and time (12/6, from 11:01 to 11:03).

But I confess I don’t get this. As a practical matter, when the searching criteria is sufficiently narrow and specific, a non-response is the same as a non-search. If a particular email was Brett’s, or Jennifer’s, why should the fact that it was technically scanned by in a query looking for Orin’s messages matter? More broadly, why should it matter whether the provider happens to store its database as a single database, or as multiple databases, or as lots and lots of small databases? I don’t think the Fourth Amendment regulates database administration.

Also, allow me a super-minor, technical, bordering on hopelessly-pedantic point: Although Sensorvault has files belong to an estimated 592 million people globally, I gather that the great majority of those people are non-U.S. persons who have no Fourth Amendment rights under United States v. Verdugo-Urquidez (1990). If about 1/3 of Google users opted into Location History, and if we say (to guess) that 80% of people in the United States have some kind of Google account, we’re probably in the ballpark of more like 90-100 million people who have the capacity to have Fourth Amendment rights who have their data in the database (and would therefore have rights against geofencing if the Fifth Circuit was right, and the Fourth Circuit was wrong, on the search question). Obviously, that’s still an enormously large, super big, way huge database. And maybe, depending on your theory of virtual place, including data of people with no Fourth Amendment rights still makes your constitutional “place” bigger. But I gather the 592 million figure is global users, not those with Fourth Amendment rights. (Hey, I told you it was a technical and bordering on hopelessly-pedantic point. I mean, you were warned. Okay, moving on.)

The ACLU also notes that no one argued in Carpenter that no warrant could actually be obtained for large databases. I mean, yes, that’s technically true. But if you think back to cases like Carpenter and Riley v. California, the availability of warrants to get the information was absolutely crucial to both of them. The Court adopted the pro-privacy position in those cases because the pro-privacy position enabled warrants.

To my mind, this raises the question of whether the ACLU’s position against warrants is short-sighted. Granted, I’m not in the position of giving advice to the ACLU. But it seems to me that there’s a crucial tension between warrants-are-needed arguments and even-a-warrant-isn’t-enough arguments in Fourth Amendment law. Historically, allowing warrants has been key to expanding what is covered by the Fourth Amendment. The switch from Olmstead in 1928 to Berger and Katz in 1967, changing from a rule that wiretapping is not a search to wiretapping being a search, is an interesting example. Wiretapping is a way to obtain mere evidence— the words of those engaged in crime. But in the window from 1921 until early 1967, in Warden v. Hayden, the Supreme Court said warrants for mere evidence were not allowed. This is conjecture, but I think that partially explained the switch from Olmstead to Berger and Katz: Wiretapping was not a search at a time when no warrant could be obtained to engage in wiretapping, and then was treated as a search very soon after changing the warrant rules in Warden v. Hayden to allow mere evidence warrants.

There’s a tension there, I think. The more you argue that a warrant cannot be used to conduct a kind of surveillance, the harder it becomes to argue that a warrant is needed to conduct that kind of surveillance in the first place. As a practical matter, the privacy-maximizing position may be pro-warrant.

(3) The Fact That There Is Never A Known Target.

The ACLU also suggests that geofence warrants are unique because there is never a target. It quotes the Fifth Circuit’s passage where it says the following:

Indeed, the quintessential problem with these warrants is that they never include a specific user to be identified, only a temporal and geographic location where any given user may turn up post-search.

But that’s how a lot of warrants work. This is nothing new. The Supreme Court emphasized this in Zurcher v. Stanford Daily:

Search warrants are not directed at persons; they authorize the search of places, and the seizure of things, and as a constitutional matter they need not even name the person from whom the things will be seized.. . . The critical element in a reasonable search is not that the owner of the property is suspected of crime but that there is reasonable cause to believe that the specific “things” to be searched for and seized are located on the property to which entry is sought.

So, for example, you can have a warrant to go seize drugs in a house, even if you don’t know who owns the house, who put the drugs there, or where the people are. To be sure, arrest warrants are about people. But search warants are about places.

(4) The Scope of the Ruling.

Finally, in response to my last point, about the extraordinary significance and scope of the ruling, the ACLU suggests that sneaky government lawyers, especially in the national security arena, will fake concern with the case but get around Smith somehow, even possibly by engaging in sneaky tactics or even wrongdoing to do it. I served as a lawyer at the U.S. Department of Justice myself, and that is not at all my experience with lawyers in the executive branch generally, or at DOJ specifically. But even among those who think that is how government lawyers work, note that the ACLU does not seem to contest that the reasoning of the Fifth Circuit’s decision would, if taken seriously, have tremendously far-reaching effects. We disagree only on whether that is a bug or a feature.

The post The ACLU’s Response to My Post on the Fifth Circuit’s <i>Smith</i> Ruling—And My Reply to the ACLU appeared first on Reason.com.