Next week the Supreme Court will hear oral argument in Glossip v. Oklahoma. Death row inmate Glossip claims that the prosecutors at his murder trial withheld evidence from him. In a curious twist, the State of Oklahoma has reversed its long-held position supporting Glossip’s conviction and now joins Glossip. I have filed an amicus brief for the murder victim’s family, presenting important facts about the case the parties have concealed from the Court. In this three-part series, I review the true facts of the case. Working together, Glossip and Oklahoma have concocted a phantom denial of evidence. In fact, the prosecutors never withheld any evidence from the defense. The Supreme Court should rapidly affirm the lower court’s decision upholding Glossip’s conviction and death sentence—and help bring the victim’s family closer to closure after more than two decades of litigation.

In this first post, I demonstrate that the alleged violation of Brady v. Maryland (requiring the State to provide exculpatory evidence to a defendant) simply never happened. The evidence that Glossip alleges prosecutors withheld was, in fact, fully known to the defense, as my amicus brief explains. Tomorrow, in the second post, I will review Glossip’s and Oklahoma’s (non)responses to this decisive point. Their silence in briefing before the Court is powerful support for my position. Finally, in the last post, I draw some broader conclusions about non-adversarial litigation such as this one. This case presents a cautionary tale about the dangers of courts simply accepting an elected prosecutor’s confession of “error,” which may be politically motivated.

The story begins on January 7, 1997, when authorities found the slain body of Barry Van Treese in a motel located in Oklahoma City that he owned. Van Treese had been missing for several hours that day. The subsequent search for Van Treese consumed everyone associated with the motel … everyone, that is, except Richard Glossip.

Glossip managed the motel and had allowed it to fall into disrepair in the latter months of 1996. Additionally, Van Treese and his wife, Donna, suspected that Glossip was embezzling money. Van Treese had planned on confronting Glossip about these issues on January 6, 1997. But Glossip said that encounter never happened. Instead, Glossip maintained that Van Treese was his normal self on that day.

As police were searching for Van Treese the next day, suspicion quickly fell on Glossip, who provided conflicting statements and sent investigators on false leads. Later, a friend of Glossip’s—Justin Sneed—would confess that he (Sneed) had murdered Van Treese and that Glossip had commissioned him to commit the murder. In 1998, a jury convicted Glossip and he was sentenced to death. After reversal of that conviction for ineffective assistance of counsel, in 2004 a jury again found Glossip guilty and he was sentenced to death based on testimony from Sneed and other witnesses. The judge who presided over the trial found Sneed “to be a credible witness on the stand,” as quoted at p. 46 of the 2022 State’s Submission to Parole Board. At sentencing, another judge echoed this conclusion, saying to Glossip: “I would say that after observing the witnesses and hearing the testimony I have absolute confidence in the decision the jury reached, both to convict you, to find the aggravators and to impose the sentence of death,” as quoted at p. 48 of the same 2022 submission.

In 2007, the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals (“OCCA”) affirmed Glossip’s conviction and sentence, rejecting Glossip’s claim that the evidence only proved his was an accessory after the fact. In the years since, courts have rejected multiple challenges by Glossip to his conviction and death sentence.

Nearly two decades later, Oklahoma was preparing to execute Glossip when a new Attorney General, Gentner Drummond, was elected. Shortly after assuming office in January 2023, and apparently sensing political opportunity, the new Attorney General hastily commissioned an “independent” review of Glossip’s conviction. Conveniently, General Drummond hired Rex Duncan, his lifelong friend and a political supporter who possessed limited experience in capital litigation. Duncan suddenly discovered “new” evidence the prosecution had purportedly concealed from the defense.

As the tale is told in Glossip’s and Oklahoma’s briefs before the Supreme Court, the trial prosecutors withheld from Glossip’s defense team information about Sneed’s lithium usage and related psychiatric care. This story rests on an interpretation of notes the prosecutors took during a pretrial interview of Sneed. Specifically, General Drummond asserts that the handwritten notes indicated that Sneed told the prosecutors “that he was ‘on lithium’ not by mistake, but in connection with a ‘Dr. Trumpet.'”

Before the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals (the “OCCA”), Oklahoma’s highest court on criminal issues, five judges considered General Drummond’s confession of error and were unimpressed. In April 2023, in a detailed opinion, the OCCA unanimously concluded that the Attorney General’s concession was “not based in law or fact.”

In May 2023, Glossip sought certiorari, supported by Attorney General Drummond. The Court re-listed Glossip’s petition twelve times through the end of 2023.

In January 2024, the Supreme Court granted certiorari to review questions relating to the Court’s jurisdiction and the implications of “the State’s suppression” of Sneed’s “admission he was under the care of a psychiatrist ….” Because no one was defending the OCCA’s judgment below, the Court appointed Chris Michel, a very capable appellate lawyer in Washington, D.C., to defend it as Court-appointed amicus.

The Supreme Court lacks jurisdiction in this case, for the reasons explained in briefs by the Court-appointed amicus, Utah and six other states, and the Criminal Justice Legal Foundation. But more important, Glossip’s conviction should be affirmed because the prosecutors never suppressed anything.

Here’s what really happened during the prosecutors’ interview of Sneed two decades ago: On October 22, 2003, before Glossip’s retrial, prosecutors Connie Smothermon and Gary Ackley interviewed Sneed, with Sneed’s counsel present. Smothermon and Ackley both took notes. Read in context, the notes show that Sneed told the group that members of Glossip’s defense team had previously visited him (Sneed) and questioned him about being “on lithium?” and a “Dr[.] Trumpet?” Smothermon and Ackley simply took notes recording what Sneed recounted about questions from Glossip’s own defense team!

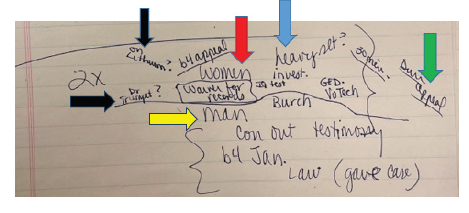

Turning first to Smothermon’s notes, General Drummond argues that the prosecutor had “taken handwritten notes confirming her knowledge of Sneed’s diagnosis and treatment”—e.g., treatment for a psychiatric condition by lithium by a Dr. Trumpet. But General Drummond fails to quote Smothermon’s notes accurately, much less discuss their context or meaning in any detail. Smothermon’s note regarding lithium contains a question mark—e.g., her note reads, “on lithium?” And her related note about “Dr[.] Trumpet” likewise contains a question mark. You can see the notes in question in the image below—with “on lithium?” and “Dr[.] Trumpet?” flagged with black arrows:

Stepping back to examine the surrounding context of these two notes reveals that Smothermon was simply recording Sneed recounting what Glossip’s defense team was

questioning him (Sneed) about—hence, the two question marks reflecting questions being asked. Smothermon’s adjoining notes reflect two visits (“2X”) by defense representatives—with notes about the two visits separated by a curving line.

Turning to the first visit, as shown by the note flagged with a red arrow above, Sneed’s visitors were “women.” As shown by the notes flagged with a blue arrow, that visit involved an investigator (“invest.”) who may have been heavy set (“heavy set?”). As shown by the notes flagged by the green arrow, the defense representatives may have been involved in Glossip’s earlier direct “appeal.” And, finally, as shown by the notes flagged by the two black arrows, the women questioned Sneed about (1) whether he was “on lithium?” and (2) a “Dr[.] Trumpet?”—i.e., questioned by the women representing Glossip. Thus, read in context, the key words in Smothermon’s notes reveal that Sneed was recounting not what Smothermon had independently learned (much less confirmed) but rather what questions Glossip’s defense team was asking Sneed.

While General Drummond fleetingly (and inaccurately) discusses Smothermon’s notes, he fails to substantively discuss the notes taken by the prosecutor seated next to Smothermon during the interview, Gary Ackley. Ackley’s contemporaneous notes interlock with Smothermon’s and confirm that the prosecutors were merely recording Sneed recounting two meetings with the defense team.

At the top part of his notes, Ackley wrote that the witness (i.e., “W” or Sneed) was “visited by 2 women who said they rep Glossip – heavy 1 ‘Inv’ & 1 ‘Atty’ – Appellate?” This important sentence in Ackley’s notes is flagged by the red arrow below:

Ackley’s notes further indicate, as flagged by the blue arrow above, that the two women who “said they rep[resented] Glossip” were “1 ‘Inv’ & 1 ‘Atty’ – Appellate?”—that is, the women who visited Sneed were an investigator and an (appellate?) attorney representing Glossip. Ackley’s notes reflect, as flagged by the black arrow above, that it was these two women who asked Sneed about lithium (“Li”). And, as flagged by the green arrow above, Sneed indicated to Glossip’s defense representatives that the lithium was being prescribed in connection with a “tooth pulled.” Further, as flagged by the orange arrow, the women asked Sneed about “Nurse’s cart record discrepancies v. W’s [i.e., Sneed’s] jail permanent record”—i.e., issues about Sneed’s medical history. And Glossip’s defense team also asked Sneed about an “IQ test” and “GED, etc.”

That Ackley’s notes correspond so closely with Smothermon’s notes begs the question why General Drummond fails to discuss what Ackley recorded in his notes—and has even failed to include all of Ackley’s notes before the OCCA and the Supreme Court. General Drummond’s (and Glossip’s) omission of Ackley’s notes is deceptive. The text of Ackley’s notes leave no doubt that Sneed was being asked about lithium and a possible doctor by women representing Glossip.

Thus, during their October 22, 2003, pretrial interview, Smothermon and Ackley simply recorded Sneed recounting a first interview by two women representing Glossip. Did such an interview by the defense team take place? It clearly did.

In earlier litigation before the OCCA, the Oklahoma Attorney General’s Office filed a sixty-two-page opposition to Glossip’s Fourth Successive Petition for Post-Conviction Release. That opposition explained that on April 16, 2001, before Sneed’s first conviction had been reversed, Glossip’s post-conviction attorney, Ms. Wyndi Hobbs, visited Sneed in prison. Hobbs was with an investigator named Ms. Lisa Cooper. During the meeting, attorney Hobbs told Sneed that it looked like Glossip would get a new trial and that there was a good chance that Sneed would be called to testify again. Hobbs indicated that she was going to “set up a second meeting and take [Sneed] an affidavit to review and sign.” Apparently, Sneed “signed releases for juvenile, jail, prison and criminal records.”

These references in the record establish that Glossip’s defense team met with Sneed—i.e., a meeting with two women (attorney Wyndi Hobbs and investigator Lisa Cooper). That such a meeting occurred reinforces the conclusion that Smothermon’s and Ackley’s notes simply reflect Sneed recounting defense team questions.

Of course, if the prosecutor’s notes merely record Sneed recounting questioning from the defense team, the notes could not reflect information withheld from the defense. The notes would reflect information about the defense. No Brady violation could even possibly exist. Glossip and the Oklahoma A.G. have simply concocted a phantom constitutional claim lacking any basis. And they have subjected the victim’s family to additional, frivolous litigation on top of two decades of earlier litigation.

So do Glossip and Oklahoma have any response to these damning arguments? Their (non)response is the subject of tomorrow’s post.

The post Glossip v. Oklahoma: The Story Behind How a Death Row Inmate and the Oklahoma A.G. Concocted a Phantom “Brady Violation” and Got Supreme Court Review (Part I) appeared first on Reason.com.