In yesterday’s post, I discussed Glossip v. Oklahoma—a case that the Supreme Court will hear next Wednesday about allegations that prosecutors withheld evidence in a death penalty trial. In that post, I reviewed my amicus brief for the murder victim’s family, which contains extensive documentation proving that the prosecutors never withheld any evidence. In this second post, I discuss Glossip’s and Oklahoma’s (non)responses to the facts that I presented. The parties’ failure to respond confirms that their Brady claim is concocted and that they are forcing the victim’s family to endure frivolous litigation. Tomorrow, in my third and final post, I will explain why courts should be cautious before accepting an apparently politically motivated confession of “error” from a prosecutor.

In Glossip, the underlying question before the Supreme Court concerns whether state prosecutors withheld evidence from Glossip’s defense team before his 2004 trial. In that trial, Glossip was found guilty of commissioning his friend, Justin Sneed, to murder Barry Van Treese. Glossip was sentenced to death. Now, nearly two decades later, Glossip argues that newly released notes from the prosecutors show that they withheld information about Sneed’s lithium usage and treatment by a psychiatrist. And, curiously, Oklahoma Attorney General Gertner Drummond agrees. Drummond has joined Glossip in asking the Supreme Court to overturn the conviction and capital sentence.

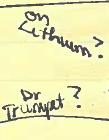

As I reviewed yesterday, Glossip’s and General Drummond’s argument rests primarily on four handwritten words in prosecutor Smothermon’s notes:

According to Glossip and General Drummond, these few words “confirm” Smothermon’s knowledge of Sneed’s treatment for a psychiatric condition by lithium by a “Dr. Trumpet” (later claimed to be a Dr. Trombka). But stepping back and reading the notes in context reveals a much different interpetation. Here are Smothermon’s notes surrounding the four words in question:

In yesterday’s post, I explained that looking at all of her notes reveals that Sneed was merely recounting what the defense team was questioning him about—not what the prosecutors had discovered. The defense team interview is reflected in the reference to “2x” (two interviews), including one by “women” that was “b4 [the] appeal” who were an “invest[igator]” and a person involved in the “appeal.”

To the extent any question remains, the corresponding notes from the other prosecutor at the interview (Gary Ackley) show even more directly that Sneed was simply recounting a defense interview. The first line of Ackley’s notes from the Sneed interview reads “W was visited by 2 women who said they rep[resented] Glossip—heavy—1 “inv” & 1 “Atty” Appellate?” Read for yourself:

As I pointed out yesterday, if the prosecutors’ notes record what happened during a defense interview, obviously no Brady violation could exist. Because the prosecutors were simply recording what a state’s witness recounted about questions asked of him by the defense team, the notes cannot contain information withheld from the defense.

In today’s post, I review Glossip’s and General Drummond’s failure to respond to these facts. As with yesterday’s post, today’s post summarizes my amicus brief and also additional factual material contained in an appendix to my brief (linked here as a single document).

Glossip and General Drummond contend that the four words in the notes mean that the prosecutors possessed information that they should have disclosed to the defense. My contrary interpretation prompts the obvious question of what do the prosecutors say their own notes mean. The authors’ explanation of what their own handwriting means would seem to be at least relevant to the discussion. But, surprisingly, General Drummond has not even asked the prosecutors what their notes mean.

Here’s the story of behind Drummond’s remarkable lack of curiosity:

Shortly after assuming office in January 2023, and perhaps sensing political advantage, General Drummond ordered an investigation into Glossip’s conviction by an allegedly “independent” investigator, Rex Duncan. Duncan, its turned out, was a lifelong friend and political supporter of Drummond. General Drummond paid Duncan handsomely to produce a report on the case. But Duncan’s report relied almost completely on an earlier report from the anti-death penalty law firm, Reed Smith. Duncan actually cut and pasted sections from the Reed Smith report directly into his.

In preparing his report, Duncan interviewed Smothermon twice. But Duncan never substantively explored what her notes meant. First, on March 15, 2023, Duncan spoke to Smothermon for about thirty minutes. During that interview, Duncan did not ask Smothermon about the notes in question, as confirmed by an email Smothermon immediately sent to the Attorney General’s Office.

Second, on the next day, March 16, 2023, Duncan briefly called Smothermon back. During that three-minute call, Duncan conveyed an interpretation of the notes provided by Reed Smith. Duncan asked Smothermon about a reference in her notes to a “Dr. Trumpet.” Smothermon then asked to see the note in question, which she had written about two decades earlier. Duncan responded there was “no need” and quickly ended the call. The entire call took about only three minutes. Smothermon then sent another contemporaneous email to the A.G.’s Office, memorializing that this call was abbreviated and non-substantive.

Since then, General Drummond has been asked (at least) three times to talk to Smothermon and Ackley about what their notes really mean—but he has obstinately refused. First, in May 2023, prosecutors at an Oklahoma District Attorney’s Association (ODDA) meeting asked General Drummond personally to talk to the two prosecutors about their notes. ODDA prosecutors told Drummond that because he had never spoken with Smothermon or Ackley, he could not know what their notes meant. Drummond reportedly responded: “I accept that criticism.” Drummond was also told that if he spoke with Smothermon, he would learned that her notes were about what Sneed remembered about his meetings with defense attorneys. Drummond did not respond to this concern.

Second, on behalf of my pro bono clients (the Van Treese family), in a telephone call with General Drummond on May 24, 2023, and a follow-up letter the next day, I said that Drummond should talk to Smothermon and Ackley about the true meaning of their notes. See May 25, 2023 Letter at 2 (“I believe that if you talk to the prosecutors who took the notes (Connie Smothermon and Gary Ackley), you will be able to quickly confirm that the notes recount what the defense knew—not what prosecutors knew.”). Drummond’s response to me (contained in the link above) ducked the subject. In the sixteen months since, Drummond has not followed up my suggestion that he go to the source of the notes.

And third, Smothermon herself has contacted the Attorney General’s Office and asked the Office to review the notes with her. General Drummond’s Office has declined.

In sum, despite repeated requests, the General Drummond has not discussed with the prosecutors their notes, much less attempted to discuss what is apparent from their face—e.g., that the notes merely describe what happened when Sneed was “visited by 2 women who said that they rep[resented] Glossip.” Against this backdrop, the reasonable conclusion is that Drummond is not seeking to determine what the prosecutors’ notes really mean. Instead, he remains willfully blind to the facts.

After I filed my amicus brief pointing all this out to the Supreme Court, General Drummond filed a reply brief. But he did not respond specifically to my arguments, including my detailed examination of the text of the notes in question. Instead, all that Drummond said was that my brief “offer[ed] alternative explanations for the notes by reference to extra-record materials.” (Okla. Reply at 9)

General Drummond’s reply is deceptive. First, as explained this post above and in my post yesterday, my brief offered an “alternative explanation” to Drummond’s reading of prosecutor Smothermon’s notes based on the notes’ text. For example, the notes refer to “on lithium?” and “Dr[.] Trumpet?” Drummond omits the two question marks from his brief, which obviously suggest lack of certainty and point to Sneed being asked questions. Drummond also fails to explain who the “women” in the notes might be … other than the two women on the defense team who I have identified. And clearly these notes are in the record—they are the very notes that Drummond claims constitute grounds for reversal.

Second, General Drummond never discusses the parallel, confirming notes taken by prosecutor Ackley, who was seated next to prosecutor Smothermon during the Sneed interview. Drummond does not deny that the notes I presented to the Supreme Court are, in fact, Ackley’s notes. Instead, Drummond apparently takes the position that Ackley’s notes are “extra-record materials”—a convenient omission from the record, because it was Drummond himself chose to leave them out! And in any event, when it is now clear that Ackley’s notes are highly relevant to the issue pending before the Court, why doesn’t Drummond admit that he possesses in his Office’s files parallel notes fully confirming my interpretation of Smothermon’s notes?

It turns out that General Drummond has included at least part of Ackley’s notes in the record. (JA939, discussed in my brief at 11 n.6). Accordingly, it is appropriate for the Supreme Court to look at the rest of Ackley’s notes under the doctrine of completeness, recognized in both federal law (Federal Rule of Evidence 106) and state law (Okla. Stat. tit. 12 § 1207).

In addition to ignoring the notes’ text, General Drummond fails to discuss what the prosecutors themselves say their handwritten notes mean. Drummond seem to think it is enough to say that the prosecutors’ interpretation is “extra-record”—which is just another way of saying that he has contrived to remain willfully blind to avoid learning what the two prosecutors say their own scrawled notes mean. The Supreme Court has granted certiorari to review Glossip’s and General Drummond’s claim that the prosecutors’ notes reflect information that the prosecutors knew and intentionally withhold from the defense. It is extremely odd to have an entire case move forward without Drummond and Glossip even telling the Court what the prosecutors themselves say their writing means.

As recounted in my amicus brief, the prosecutors say that their notes mean exactly what their text indicates. Smothermon says her notes recorded that Sneed was recounting what defense team members were asking him:

Sneed answered “2X” to my question of whether anyone else had spoken to him which was my usual question at the conclusion of an interview with an in-custody witness. Sneed told us … [t]he first visit was from two women before his appeal (of his first conviction). One he described as heavyset investigator. They asked him to sign a waiver for records—IQ test, GED, VoTech, and asked him questions about lithium and Dr. Trumpet. The question marks after those two words indicate that the women asked him those questions.

And Ackley likewise says that his notes reflect Sneed was recounting a defense interview:

[My] notes reflect that Sneed (W-witness) was visited by 2 women who said they represented Glossip, one was heavy, an investigator and one was an attorney. I noted appellate as a thought to the identity of the visitors. Sneed said the visit lasted about 30-40 minutes. They asked Sneed to sign a waiver so they could review his records regarding IQ tests, GED, etc. With an arrow, I noted Sneed said “on lithium when administered” regarding the visitor’s questions about IQ testing.

In sum, General Drummond is asking the Supreme Court to reverse a murder conviction and death sentence based on an interpretation of four words in one prosecutor’s notes. But Drummond ignores the true facts of the case established by surrounding context.

Glossip also had the opportunity to reply to my interpreation of the notes. But, like Drummond, Glossip fails to engage on the key facts. Notably, Glossip never denies the critical point (discussed in my post yesterday) that on April 16, 2001, two women on his defense team interviewed Sneed. If so, it would appear that Glossip has an ethical obligation to tell the Supreme Court what information his defense team learned through that interview and related investigation. And yet one can read Glossip’s brief without finding any discussion of his own defense team’s interview of Sneed—an interview in which the defense team asked Sneed about lithium and Dr. Trumpet.

In his reply brief, Glossip briefly refers to my presentation of Smothermon’s interpretation of her own notes. Glossip disparages her interpretation “as unsworn hearsay manufactured for an amicus brief.” (Glossip Reply. at 5). But why hasn’t Glossip (or General Drummond) asked her to explain her notes. Glossip briefly refers to the interview of Smothermon by Rex Duncan (discussed above). But it is apparently undisputed that, during that inconclusive three-minute interview, Smothermon asked to see her notes to interpret them, and Duncan replied there was “no need.“

Glossip’s team has also recently interviewed Ackley. But that interview apparently steered clear of the fact that Ackley was just memorializing Sneed’s recounting defense team questioning. As with General Drummond, Glossip entirely ignores the fact that co-prosecutor Ackley’s notes interlock with Smothermon’s and make clear that Sneed was recounting being “visited by 2 women who said they rep[resented] Glossip”—i.e., what the defense team knew.

In addition, the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals declined to order an evidentiary hearing on what the prosecutors’ notes mean. In rejecting Glossip’s claims, the OCCA held:

This Court has thoroughly examined Glossip’s case from the initial direct appeal to this date. We have examined the trial transcripts, briefs, and every allegation Glossip has made since his conviction. Glossip has exhausted every avenue and we have found no legal or factual ground which would require relief in this case. Glossip’s application for post-conviction relief is denied. We find, therefore, that neither an evidentiary hearing nor discovery is warranted in this case.

In his certiorari petition to the U.S. Supreme Court, Glossip declined to challenge the OCCA’s decision not to order an evidentiary hearing. Of course, in any evidentiary hearing about the notes, Glossip would have to explain exactly what his defense team knew about Sneed before the trial—a subject that he has avoided discussing.

In sum, Glossip is asking the Supreme Court to overturn his death sentence based on a concocted interpretation of the prosecutors’ notes that ignores their plain meaning. It is gobsmacking that he has gotten so far with so little. And, as a result of Glossip extending his frivolous litigation, the victim’s family continues to wait for his sentence to be carried out … 10,128 days after Glossip commissioned the murder of Barry Van Treese.

In tomorrow’s final post, I discuss how courts should handle non-adversarial litigation, such as this one—where Glossip and General Drummond are working hand-in-hand to keep the Supreme Court from learning the truth.

The post Glossip v. Oklahoma: The Story Behind How a Death Row Inmate and the Oklahoma A.G. Concocted a Phantom “Brady Violation” and Got Supreme Court Review (Part II) appeared first on Reason.com.