For two weeks in April, the top movie in America explored what would happen if Texas and California seceded from the United States. The answer, as foreshadowed in the title Civil War, was brutal internecine violence leading to probably thousands of grisly deaths.

Director Alex Garland’s “powerful vision,” opined Variety‘s Peter Debruge, “leaves us shaken, effectively repeating the question that quelled the L.A. riots: Can we all get along?” With the country’s already deep political schisms fracturing further during this presidential election year, Rodney King’s famous question suggests a more provocative answer: Maybe we can’t all get along—and perhaps we shouldn’t have to.

In January, three real deaths became central symbols in an actual fight—so far just in court, not on a domestic battlefield—between state and federal authorities. Victerma de la Sancha Cerros, 33, and her two children, ages 10 and 8, drowned while trying to cross the Rio Grande near Eagle Pass, Texas. Such deaths may be tragically routine—895 people died along the southwestern border in 2022, according to U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP)—but the circumstances in this case were not. Instead of allowing federal Border Patrol agents to mount a rescue attempt, Texas Army National Guard troops, on the order of Gov. Greg Abbott, blocked their access to the river.

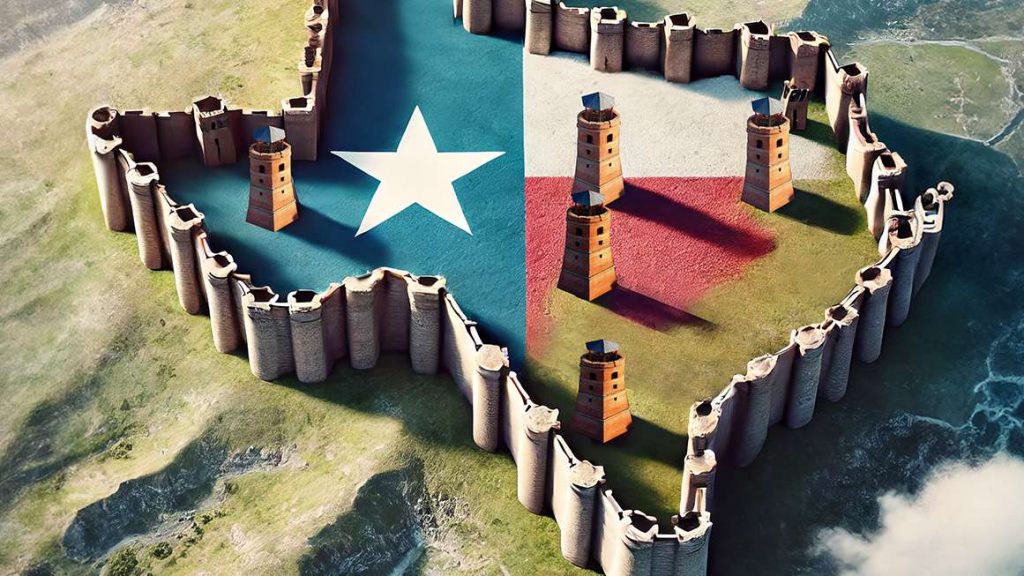

The Lone Star State has a well-earned reputation for going rogue, beginning with its decadelong prehistory as an independent republic. Abbott, frustrated with the federal government’s inability to slow the volume of illegal border crossings, launched Operation Lone Star in 2021 to nab illegal immigrants at a cost of $2 billion per year. Border crossings continued to grow after that—more than 1 million entered Texas in 2022, and then again in 2023. Abbott’s administration has since engineered a series of escalating legal and physical standoffs with the feds, who the governor accuses of deliberately evading their duty to secure the border.

Washington has responded by suing Texas over various issues, including Abbott installing floating barriers to block migrants in the Rio Grande (U.S. v. Abbott) and asserting in its S.B. 4 law the power to “regulate the entry and removal of noncitizens” (U.S. v. Texas), a task historically assigned to the federal government.

Abbott counters that it has the authority to protect state territory and keep people out, notwithstanding hoary federal laws and principles. That power, Abbott claims, is embedded in Article I, Section 10, Clause 3 of the Constitution, which provides, “no state shall, without the Consent of Congress,…engage in war, unless actually invaded, or in such imminent Danger as will not admit of delay.” The waves of undocumented immigrants and drug smugglers entering Texas from Mexico, he maintains, constitute an invasion.

Both lawsuits are still in process. In U.S. v. Abbott, regarding the river barriers, the feds had won a preliminary injunction against Texas using them in both district court and then with a three-judge panel of the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals. In July, however, an en banc panel of the 5th Circuit stayed the injunction, though the basic case still awaits trial to more fully settle the question. Judge James C. Ho, on that panel, wrote that as far as he’s concerned, if a chief executive thinks he’s being invaded, there is nothing a court can or should be able to do to gainsay him.

Courts are conflicted on that question, since Judge David Ezra of the U.S. District Court in Austin had already rejected that part of Abbott’s theory of the case. If unwanted immigrants constitute an “invasion,” he argues, then that would be an act of war justifying the suspension of habeas corpus. “It is not plausible that the Framers, so cognizant of past abuses of the writ and so careful to protect against future abuses, would have granted states the unquestioned authority to suspend the writ based on the presence of undocumented immigrants,” Ezra wrote in February, while granting a preliminary injunction blocking the enforcement of S.B. 4 in U.S. v. Texas.

“The federal government,” Abbott charged in a January statement defending his maneuvers, “has broken the compact between the United States and the States” by failing in its “constitutional duty to enforce federal laws protecting States, including immigration laws on the books right now.”

Democratic critics immediately cried foul at Abbott’s use of “compact” language in the immigration fight, noting its history as a legal rationale for Southern states to secede from the Union. Those words “sound like a call for a 21st century civil war,” former Watergate prosecutor Jill Wine-Banks warned at MSNBC.com. “The opening sentence alone…would not be out of place among the declarations of secession issued nearly 165 years ago.”

As if on cue, two weeks later, Daniel Miller, founder of the Texas Nationalist Movement (TNM), hand-delivered to Abbott’s desk a package containing 139,000 signatures of Texans calling for a statewide ballot referendum on going independent.

“This is an issue that transcends partisan divide and is, in fact, an issue of the people of Texas versus an entrenched political establishment,” Miller declared at the scene. “In this lifecycle of an independence movement, we’re outperforming Brexit, we’re outperforming Scottish independence, and we’re outperforming Catalan—and we’re outperforming everyone at every stage of the process.”

Abbott, and the Texas Republican Party, rebuffed the independence petition, barring the issue from consideration on the March primary ballot. But many Americans’ sense that this whole perpetual union thing isn’t quite working has been bubbling all over the place in this election year.

Meet the Secessionistas

Miller launched the TNM in 2005. Since then, the organization (per its website) has “spearheaded initiatives that educate the public on the benefits of self-governance, fostered community through statewide events, and advocated for legislation that aligns with our mission of independence.” The TNM currently has 210,000 Facebook followers, it runs a political action committee, and as of September its website insists the organization has over 623,000 registered supporters.

“We don’t have big Daddy Warbucks types flinging money—it’s not like that for us. We are 100 percent funded by our members and supporters,” says Miller. There are leaders at the district and local level, plus “over 5,000 statewide volunteers” who have combined to host more than 6,000 events. “Our independence movement,” he says, “is a massive operation.” So far the PAC portion of the operation has gathered only a little over $24,000 as of the end of the second quarter of this year, and by that time hadn’t spent any of it.

The TNM solicits politician signatures to the “Texas First Pledge,” which “place[s] the interests of Texas and Texans before any other nation, state, political entity, organization, or individual,” upholds Texans’ right to “alter, reform or abolish their government,” supports holding a referendum on independence, and, if such a referendum proves successful, works “toward a fair and expedient separation of Texas from the federal government.”

So far, nearly 200 candidates for state-level and (mostly) local office have signed the pledge, though the list of signatories tilts overwhelmingly toward current or former candidates instead of current officeholders.

Miller insists that if you “look at polling numbers for the issue, like a Survey USA poll in 2022, we know that a supermajority of Republicans support this issue, and we’ve got a majority of both Democrats and Republicans. We know if this gets to a vote, [independence] wins not by a little, but a lot.”

This movement for what Miller likes to call “Texit” has a legal argument resting in Article 1, Section 2 of the Texas constitution, which reads in part: “All political power is inherent in the people, and all free governments are founded on their authority, and instituted for their benefit….They have at all times the inalienable right to alter, reform or abolish their government in such manner as they may think expedient.” If you oppose giving Texans the chance to have a binding, meaningful vote on secession, Miller believes, you are un-Texan, even un-American, rejecting the core small-r republican principle that government power derives justly from the people and nowhere else.

That logic may play in Texas, but Washington, D.C., is a whole different ball game.

Secession is—of course, of course!—a settled matter nationally, a no-go. The Supreme Court’s 1869 decision in Texas v. White put paid to the idea there was some reversible voluntary component to membership in this union of states. That case involved a suit over bonds that had been issued by the government of Texas during its time in the Confederacy. The Court ruled that even in rebellion, Texas for all legal purposes remained a part of the Union and therefore was subject to its laws.

“When Texas became one of the United States, she entered into an indissoluble relation,” wrote Justice Salmon Chase. “The ordinance of secession…ratified by a majority of the citizens of Texas, and all the acts of her legislature intended to give effect to that ordinance, were absolutely null….The State did not cease to be a State, nor her citizens to be citizens of the Union….It is needless to discuss at length the question whether the right of a State to withdraw from the Union for any cause regarded by herself as sufficient is consistent with the Constitution of the United States.” Case closed.

Still, Americans have stubbornly continued to “discuss at length” the idea of secession, with varying levels of passion. To which Sanford Levinson, a constitutional scholar at the University of Texas, has a brutal realpolitik rejoinder: “It was decided in the case of Grant v. Lee.” That is to say, the military struggle between Ulysses S. and Robert E. settled the question definitively. Whether an exit from the Union actually could happen, Levinson thinks, is less a question of constitutional law and more about political power and facts on the ground at the moment.

Levinson wishes for curiosity’s sake as a political scientist—he wants those data!—that the independence referendum had made the March ballot. He sees the idea as having cultural legs, noticing the number of recent scholarly books from across the political spectrum taking seriously the idea of secession during this time of national division and occasional unrest. Many embrace the controversial originalist “compact” theory of the uniting of the states: that the Union was not necessarily meant to last forever, but rather formed of sovereign states who reserve the right to depart it if their citizens so choose.

Abbott was quick during a March 60 Minutes appearance to dispute the “false narrative” that his invocation of “compact” indicated a tilt toward Texan independence. His state GOP, on the other hand, in 2022 inserted in its platform language that “We urge the Texas Legislature to pass bill in its next session requiring a referendum in the 2023 General Election for the people of Texas to determine whether or not the State of Texas should reassert its status as an independent nation.” Despite that unambiguous platform support, Republican Party pooh-bahs have thrown up roadblock after roadblock to a vote on independence.

In December 2023, then-state GOP Chair Matt Rinaldi denied the validity of the TNM’s 139,000 referendum signatures—even though only 97,709 were needed—partly on the technical grounds that they were allegedly turned in one day late. (The ruling relied on interpreting the requirement of turning in signatures “before” the deadline as meaning the day before, as opposed to before the end of business on deadline day. The day before the deadline day was a Sunday, and the state party’s offices were closed.)

The TNM sued to get the question on the ballot, but in January the Texas Supreme Court declined to consider it. “We know the support is there,” Miller says, “but we are fighting against an entrenched establishment that does not want the issue to come to a vote.”

While Rinaldi stood by his procedural objections (which also included that the majority of names were e-signatures, and therefore invalid under his read of Texas election law, applying the same rules for candidate petitions to this issue petition; Miller insists a section of Texas business and commerce code that allows electronic signatures anywhere a signature is legally required should settle the matter), he also admitted on a Texas talk radio show in January that he thought it was a bad political look to have secession on a primary ballot in 2024. The question, he feared, would attract “people who don’t usually vote in the GOP primary…moderate voters motivated to vote against it.” Which in turn might have overshadowed or even negatively impacted other key issues, such as school choice, for a Republican Party that is trying to move further right on that and other issues where nonsecessionists might disagree with Rinaldi’s preferred positions.

There is another complication on the way to Texit: Texas has no established legal method for holding a voter referendum. The state Legislature would have to create a mechanism. Two different TNM supporters introduced such bills in 2021 and 2023, but neither got as much as a hearing, let alone a vote from the relevant committee. Neither legislator is still in the Texas House. Miller insists he’s confident that a bill will be resubmitted in the not-too-distant future, but he doesn’t want to tell the press who would introduce it or when, for fear of alerting his political enemies. In May the Texas state GOP elected a new chair and vice chair who are both signed on to the “Texas First” pledge (Rinaldi did not seek reelection), then in June, the state GOP’s new 2024 Legislative Priorities and Platform document repeated its support for holding an independence referendum.

Travis County Republican Party Chair Matt Mackowiak, who personally finds secession to be “unpatriotic and fundamentally completely unworkable,” argues that Rinaldi’s objections to the petition can be read at face value: The state chair truly believed e-signatures should not count. As for the party’s unequivocal platform boosting of an independence referendum, Mackowiak hems that while “technically everything in the platform of the Republican Party is something elected officials are duly bound to support,” one can’t assume every GOP official or officeholder has fully incorporated every sentence into their governing strategies and philosophy. Besides, calling for a referendum to be held does not obligate any Republican to actually vote in favor of secession.

Secession for Everyone

Miller says he gets contacted on a weekly basis by pro-secession activists from other states. Where does the keenest interest come from? The Live Free or Die state of New Hampshire, the statehood latecomers in Alaska, and geographically/politically polarized California. A new group inspired in part by Miller’s strategy calling itself the New Hampshire Independence Movement, or NHEXIT, announced its launch in July, run by Free State Project chair Carla Gericke. “We must take back our government and work to guarantee the protection of the rights and basic necessities of New Hampshire residents,” Gericke said in a press release announcing NHEXIT’s launch; the group is intended to “create a community of pro-independence Granite Staters, and work to secure a self-governed future for New Hampshire.”

New Hampshire already saw a bill to create a ballot measure calling for secession via constitutional amendment introduced in the 2022 legislative session; it was debated openly on the floor after a committee deemed it “inexpedient to legislate.” Thirteen representatives voted against the committee decision to sideline the proposal.

Two new secession-related bills were introduced in 2024 as well, says Matthew Santonastaso, the legislator who introduced it last time. But “secession in New Hampshire is old news now. No one cares anymore,” he said in an April phone interview. The only reason his 2022 effort was allowed to have open floor debate, Santonastaso believes, is that Democrats thought any Republican on record as supporting secession would soon be out of a job.

Democrats indeed held a hearing later in which they tried to get all 13 booted off ballots for being insurrectionists. “But the public was not phased,” Santonastato says. “They have mixed opinions, some favorable, but it didn’t hurt me at all. Nor did it benefit me much. There were not too many secession voters out there.”

Having the threat of secession available as a tool for dissident politicians and citizens can be important in and of itself, argues F.H. Buckley, a law professor at George Mason University and the author of the 2020 book American Secession: The Looming Threat of a National Breakup. A Canadian familiar with the independence politics of Quebec, Buckley believes that raising the possibility can be a significant bargaining chip, a way for states to make it very clear that serious issues need to be settled with the feds, even if actual secession is very unlikely to materialize.

It’s also possible, though, that in the current American partisan context a federal government run by one party would be highly unlikely to show any respect for the independence-threatening complaints of a state run by the other. As Buckley mused in an April phone interview, “Trump or any Republican looking at California and what the electoral map would be like without California might just say, ‘That works for me.'”

As the state-level growth of first medical and then recreational marijuana shows, states can, if they really want to, depart from federal rules without departing from the Union. And in a narrowly divided country, partisan control over the federal government can and will change hands with some frequency, rendering some secession-fueling policy disputes (such as immigration in Texas) potentially moot.

Miller for his part insists that a GOP presidential victory in 2024 would not slow the TNM’s progress. “When it was evident Trump was going to be president [in 2016], media outlets and pundits predicted it would be the death of us. We literally grew at the same rate during Trump as we did during Obama,” he says. “Texas has been very clear we want a strong border and sane immigration policy, and neither one of those will ever be provided by the federal government.”

Miller says he does not want to repeat the mistakes of Scottish independence activists, who he says saddled the question of independence with overly specific visions of what paths the newly freed political entity would pursue. Secessionists merely “start with the realization that the federal government is unfixable,” he says. “We don’t get to vote for 2 and a half million unelected bureaucrats, or unaccountable federal judges. We don’t get to vote on the senators from New York or California or Pennsylvania.”

While Miller is careful to not make his secession movement seem explicitly right-wing, many of the issues inflaming a feeling that red staters just don’t belong in a blue-dominated nation are coded as conservative. Gender transitions—or even just the display through clothing and deportment of a different gender than one’s genitals would indicate—gets some Texans hot.

While the Biden administration wants to ensure there is no discrimination in health care based on gender identification, Abbott wants anyone who has anything to do with a minor seeking any “gender-affirming care” to face criminal child abuse charges, wants to bar any Texas teacher from wearing clothes not traditionally associated with their assigned gender at birth, and cheers state universities for banning drag shows on campus. Abbott’s Texas passed a law that, while not naming drag shows explicitly, barred “sexual gesticulations using accessories or prosthetics that exaggerate male or female sexual characteristics” around kids, which many activists saw as a disguised drag show ban. That law in 2023 had its enforcement blocked by, wouldn’t you know it, a federal judge. Many Texans are not down with the Biden administration’s generally protransgender attitudes and actions—and for those who care passionately about them, these sort of culture issues can truly energize feelings of not wanting to tolerate co-nationals on the other side.

Secession and the Libertarians

Under the rebrand of “national divorce,” the concept of secession has been endorsed by a handful of congressional backbenchers, such as Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene (R–Ga.), and also the current management of the Libertarian Party.

Certain strains of American libertarianism—particularly those associated with the Mises Institute, which sponsored a prescient 1995 conference on the matter that led to the 1998 essay collection Secession, State and Liberty—have long been fascinated by secession as a tool for chipping away at massive centralized power. They offer national divorce as a comparatively painless way to resolve angry and seemingly intractable ideological and cultural disputes, allowing people to opt out of each other’s political decisions.

But this approach treats individual residents of a given state as a lumpen mass, while giving too much consideration to the alleged interests of the states that constitute the Union: those still-massive centralized powers with a monopoly on force and wealth extraction. American states are as riven internally as they are in relation to the federal government or to other states. (Indeed, some of Abbott’s border-control measures happened in a city whose own mayor was against them.) It is flatly impossible that everyone in a given state is going to affirmatively want to leave the U.S., or that the losing minority in any breakaway is going to accept forced denaturalization without some sort of a fight.

Using the crude yardstick of the 2020 presidential election, voters in 42 of the 50 states supported both major-party candidates by at least one-third. If the five states with the largest Donald Trump majorities (Wyoming, West Virginia, North Dakota, Oklahoma, and Idaho) had seceded after Joe Biden was sworn in, over a million voters combined even in these small states would be effectively disenfranchised from their home country.

Secession at the level of the state as a political unit inherently ignores the choices and interests of the individual. State-level secession doesn’t come anywhere close to solving the underlying problem of America’s political (or affective) polarization. But an important question, especially for libertarians, remains: What are the chances that a seceded state will be more free?

Consider Texas. The Lone Star State would likely aim to lower taxes, but its government may be strapped for cash once cut off from federal subsidies. A Texas Monthly report from February estimated that, after accounting for such benefits as Social Security, Medicaid, and the state university system, Texas receives net benefit from the federal government of about $45 billion a year.

Texas would be far more likely to allow parents to make choices about how their education money is spent than the U.S. writ large, even though the state has yet to pass full school choice. But Abbott’s administration also wants to restrict citizens’ online privacy, free speech on campus, and ability to move about freely without fear of being suspected of breaking a border-related law (especially for non-Anglos) much more than large-population competitors such as California and New York.

An independent Texas would have at least initial physical possession of all the choppers, tanks, and other materiel currently stored at major Army depots at Red River and Corpus Christi, though how nominal physical possessions of the federal government within Texas’ border, which also includes big chunks of the space program, will be divvied or moved is one of the many practical details no one involved in the TNM has tried to game out much in public. As Britain’s post-Brexit experience with the European Union has illustrated, being in the junior negotiating position on such massive deliberations is expensive and fraught.

A Peaceful Secession?

Would the federal government, à la 1861, simply block secession by force? Miller contends that this would be untenably impractical—and hypocritical.

U.S. foreign policy has for decades been based on the moral and aspirational notion that the right of self-determination is something “to fight and die for,” he argued in an April podcast on the Civil War movie. “For the federal government to use force to the contrary right in its own backyard…would smack of hypocrisy to the greatest degree to the international community.” A federal government that suppresses democratic independence, Miller says, is one that, according to the logic of the U.S. government from the 1990s Serbian conflict on, “deserves to be bombed.”

At minimum, a U.S.-Texas war would engender “outright disobedience from the highest levels of the military all the way down to the enlisted ranks by at least 42 percent of the military, if not all,” the TNM website asserts. “Texas might be the first to leave but, if the federal government used the military to suppress the result, it certainly would not be the last.”

Miller can reel out various polls to prove that the American people want their states to have the power to leave the Union. But American Secession author Buckley doesn’t believe those kind of polls provide much information we can rely on in any state’s possible forthcoming attempt to secede.

“It’s really easy to say you hate those people in Alabama,” or to otherwise express your pique with fellow Americans by telling a pollster that your state should have the power to leave, Buckley says. “But an actual vote on secession would be serious, it would have consequences, you would think more seriously before you agree to that.” Are we really, he asks, “going to have secession over drag queen story hour?”

The post Secession Is Back in Style in Texas appeared first on Reason.com.