Initiatives related to ranked choice voting in political primaries and general elections were on the ballots in eight states and the District of Columbia. On the ballots were also an initiative that would repeal ranked choice voting (RCV) and restore plurality elections in Alaska, and to prohibit ranked choice voting in Missouri.

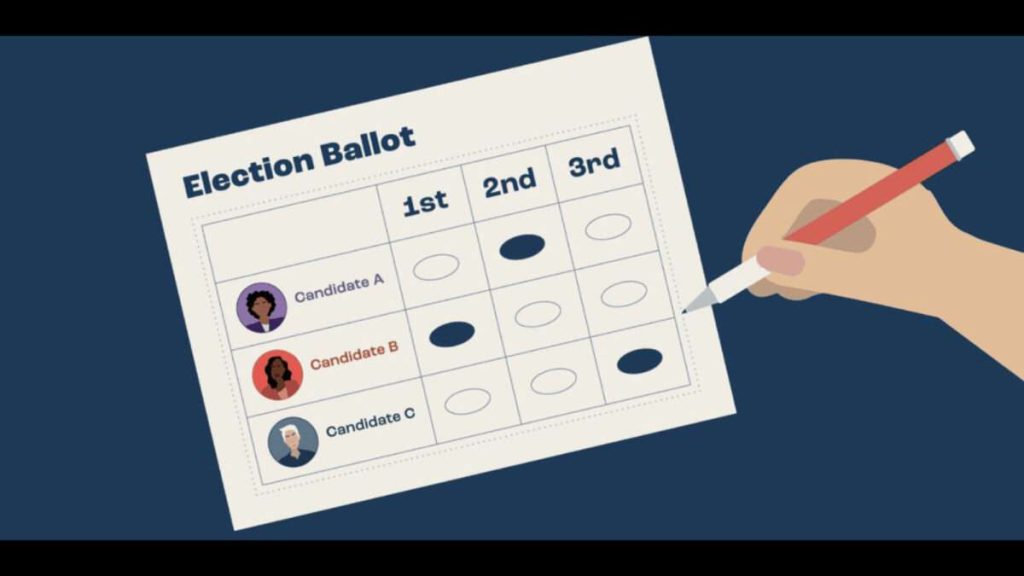

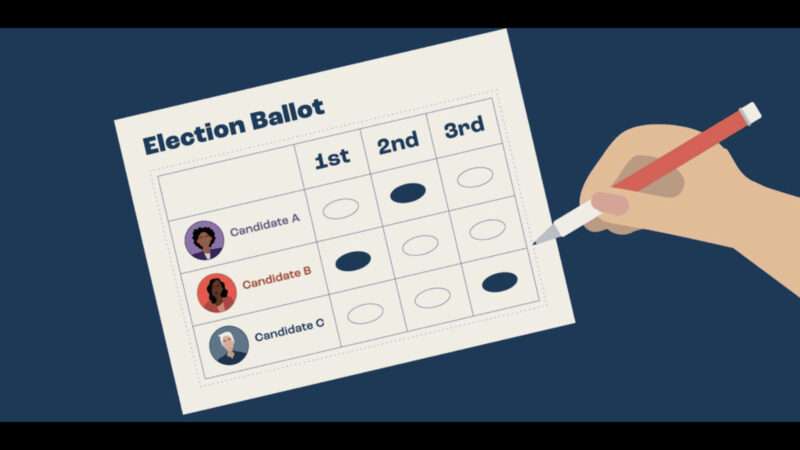

RCV lets voters rank candidates for political office by preference instead of choosing just one. If no candidate gets a majority of first-choice votes, the candidate with the fewest votes is eliminated. Voters who picked the eliminated candidate as their top choice have their votes transferred to their next preference. This process repeats, eliminating the lowest-ranked candidates and redistributing votes, until one candidate achieves a majority.

First-past-the-post plurality party primaries exacerbate political polarization because candidates are generally chosen by each party’s base consisting of relatively few but highly ideological voters. This setup pushes candidates to adopt more extreme positions to gain favor with primary voters.

Proponents of RCV argue that it helps ensure the winner has broad support and allows voters to express multiple preferences, creating a more representative outcome in multicandidate races.

Cato Institute scholar Walter Olson argued in 2021 that RCV “should hold a lot of attraction, I believe, for those of us with libertarian views.” Why? Because libertarians, he observes, “tend to be aware that the so-called political spectrum does a poor job of capturing important facts about candidates; the ones we recognize as best (or worst) on matters of liberty and the rule of law do not necessarily line up neatly along a party spectrum. For libertarians, as for other groups, RCV respects and incorporates the complexity of actual voter preferences.”

Federal courts have consistently ruled that RCV does not violate federal constitutional and statutory requirements with respect to freedom of speech, freedom of association, and equal protection under the law. Specifically, courts have found that RCV in primaries and general elections does not violate political parties’ free speech rights because it neither limits parties’ ability to express their positions nor restricts their freedom to support chosen candidates. RCV simply changes the mechanics of how votes are counted without suppressing party messaging or candidate competition.

While not all the votes have yet been counted, ranked choice voting appears to have been strongly rejected by voters in nine states. Only voters in Washington, D.C., chose to adopt RCV.

Let’s take a look at the results.

Arizona Propositions 133 and 140: The first would amend the constitution to require partisan primaries and the second would amend it to permit the adoption of ranked choice voting in elections: Both were rejected (by 59 percent to 41 percent and 58 percent to 42 percent, respectively). Basically maintaining the state’s current semi-closed primary system.

Colorado Proposition 131. Top-four ranked choice voting in primary elections and RCV for both federal and state general elections: rejected by 55 percent to 45 percent.

Idaho Proposition 1. Top-four ranked choice voting in primary elections and RCV for both federal and state general elections: rejected by 69 percent to 31 percent.

Montana Constitutional Amendment 126. Top-four ranked choice voting in primary elections for both federal and state general elections: rejected by 52 percent to 48 percent.

Montana Constitutional Amendment 127. Requires a majority vote to win state and federal general elections: rejected by 61 percent to 39 percent.

Nevada Question 3. Top-five ranked choice voting in primaries and RCV for both federal and state general elections: rejected by 54 percent to 46 percent. Note that a ranked choice voting amendment to the state constitution passed with 53 percent of the vote in 2022. (Amendments must be passed in two successive state general elections.)

Oregon Measure 117. Ranked choice voting in primary and general elections for federal and state executive offices beginning in 2028: rejected by 60 percent to 40 percent.

South Dakota Constitutional Amendment H. Replace partisan primaries with top-two primaries for state and federal elections: rejected by 66 percent to 34 percent.

Washington, D.C. Initiative 83. Semi-open primaries and ranked choice voting for all elections, beginning in 2026: adopted by 73 percent to 27 percent.

What about the initiatives that would repeal and prohibit ranked choice voting?

Alaska Ballot Measure 2. Repeal top-four ranked choice voting in primaries and general elections: too close to call now but it’s 51 percent to 49 percent for repeal. Note that RCV squeaked through in 2020 with 50.55 percent vote in favor.

Missouri Amendment 7. Prohibit ranked choice voting and require plurality primary elections: prohibit wins 69 percent to 32 percent.

The post Ranked Choice Voting Initiatives Massively Fail appeared first on Reason.com.