Let us first stipulate that Los Angeles city and county, as well as the entire Golden State, could have had the best governance in the history of human affairs, yet still there would have been property-destroying fires in Southern California this week.

When the National Weather Service issues a rare “Particularly Dangerous Situation” (PDS) fire warning for the counties south of the Tehachipis, as it did Monday afternoon, things just burn. The December 9, 2024, PDS warning preceded the Franklin Fire, which consumed 4,000 acres and destroyed 20 buildings around Malibu. A November 5 alert anticipated the next day’s Mountain Fire in Ventura County, torching 20,000 acres and 240 structures. Similar wrath followed the only two other PDS designations before this week, in October 2020 (Blue Ridge and Silverado fires, in Orange County) and later that December (the Bond fire, also in the O.C.).

From the Chumash to Raymond Chandler, Joan Didion to Mike Davis, residents of this Biblical basin have always understood the formula: Hurricane-level Santa Ana winds + extremely dry air/vegetation = brush fires. The question isn’t if, it’s how bad.

That’s where government comes in. The entities tasked by charter to protect life and property, to organize collective action in the face of community-wide challenges, should be prepared at a foundational level for the catastrophes that have cyclically and even predictably beset this mountain-ringed land since humans first started comingling with the saber-tooths: earthquakes, droughts, floods, mudslides, and fire.

Shock events, from 9/11 to the 2008 Financial Crisis to the COVID-19 pandemic, are effectively margin calls on governance; moments when citizens take a sudden, razor-keen interest in how their otherwise ignored representatives and bafflingly overlapping managerial jurisdictions anticipated, and are coping with, crisis. These are times for assessing not just individual performance, but whole systems and theories of how government should deliver on fundamental tasks.

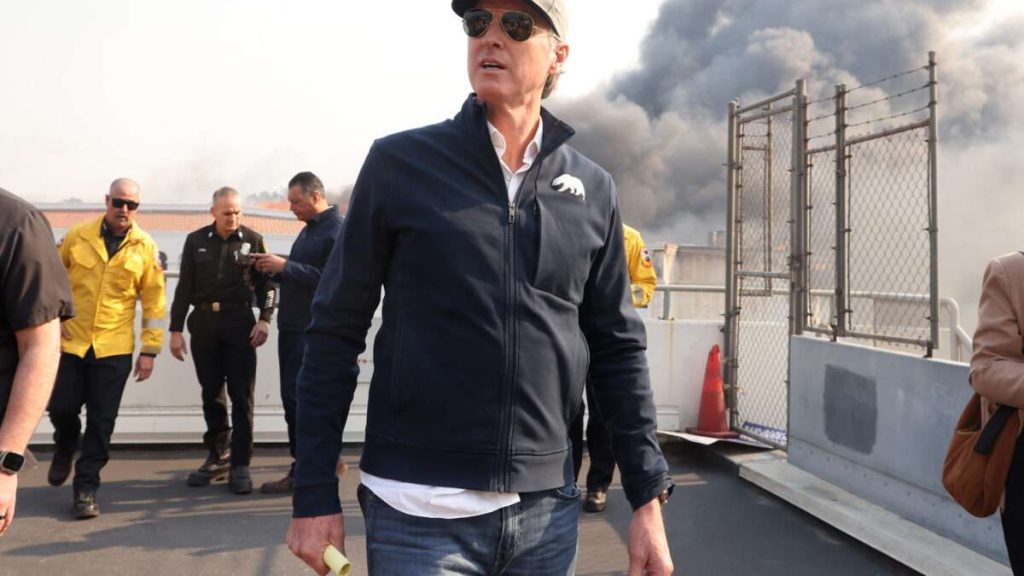

With thousands of Californians beginning to discover that their homes, businesses, and prized possessions have been incinerated, such attention is already being firehosed toward three elected officials in particular: Los Angeles Mayor Karen Bass, Gov. Gavin Newsom, and state Insurance Commissioner (yes, that’s an elected position) Richard Lara.

The results thus far, as detailed here by Reason‘s Liz Wolfe on Thursday morning, have been farcical—Bass’s 90-second brain-freeze under reportorial questioning upon belated arrival from an idiotic trip to Ghana, Newsom’s Alfred E. Neuman-esque shrug about insufficient firefighting water, and now Lara compounding California’s insurer-repelling price controls with a new moratorium on homeowner-policy cancellations and non-renewals.

Fire hydrants have sporadically run out of water, either from reservoir depletion or power shutdowns that were executed without replacement generator capacity. Blackouts still affect hundreds of thousands of residents, including many who do not live near a fire. L.A. County errantly sent out to the phones of its 10 million residents an emergency evacuation order on Thursday. Critics of governmental diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) initiatives have found examples aplenty of local fire officials prioritizing identitarian concerns.

But these are surface-level critiques compared to the systemic, long-arc government failures to do the arduous but necessary work to reduce fire risk and marshal the most precious resource in the state: water.

People gobsmacked by empty fire hydrants in Pacific Palisades have wondered, why not just stick a hose in the ocean? Well, salt water can be very damaging to equipment (including firefighting machinery) and all sorts of other things as well, so the Pacific’s bounty can only be used against conflagrations sparingly. But desalinated water sure could have come in handy this week.

How many coastal desalination plants are there between Santa Barbara and San Diego counties? Zero.

California voters in 2014 passed Proposition 1, the Water Quality, Supply, and Infrastructure Improvement Act, which authorized $7.12 billion in bond issues; it’s one of eight water-related bond-issue propositions passed so far in the 21st century. A full $2.7 billion of Prop. 1 was earmarked for “new water storage” projects, to do stuff like capture more snowmelt and rainwater in the state’s sporadic heavy-precipitation winters (such as 2022–23 and 2023–24).

So how many of those water storage projects have been built? Zero.

California, and many of its geographically smaller governing units, do a woefully insufficient (if directionally improving) job of clearing away deadwood and forest brush, as does the territory-gobbling U.S. Forest Service. Despite some recent improvements, there are still far too many non-insulated electrical lines above ground in fire country. Localized water capture in the vast, concretized floodplains between Santa Monica and Laguna Beach remains a work only beginning to progress.

These issues are devilishly hard to solve, because of engineering difficulty, competing claimants, and federal law—California’s actuarial disaster of a Fair Insurance Access Requirements (FAIR) system, after all, is a downstream product of the Housing and Urban Development Act of 1968.

But look no further than California’s 13-digit bullet train to nowhere for a reality that even Gavin Newsom supporters know in their hearts to be true: The Golden State, like so many Democratic-dominated polities, does a piss-poor job of building any damn thing, let alone projects that are both ambitious and necessary. The generalized return on taxpayer investment, compared to states like Florida, is brutal. And the modal quality of senior political leaders—from Karen Bass to Health and Human Services Secretary Xavier Becerra all the way up to Kamala Harris—is cringe-inducingly mediocre.

What is Newsom doing this week, aside from his usual mugging in front of TV cameras? Gaveling in a special legislative session he called immediately after the November election to “protect California values” against the scourge of Donald Trump.

Showily opposing MAGA has been good business for the career of Newsom and other California politicians, at least until this week. There is something about a catastrophe, and a top-of-mind reassessment of government’s role in preparing for and mitigating disaster, to potentially prioritize other values. Like competence.

The post Fires Incinerated the Facade of California Governing Competence appeared first on Reason.com.