By the time Arthur Terminiello arrived at Chicago’s West End Woman’s Club on a Thursday evening in February 1946, a hostile crowd that would swell to 1,000 or so protesters had already gathered outside the auditorium. They were outraged by the event at which Terminiello was scheduled to speak: a Christian Veterans of America meeting organized by the evangelist Gerald L.K. Smith, a flagrantly antisemitic populist and spectacularly unsuccessful presidential candidate who had founded the America First Party three years earlier.

Picketers blocked access to the building, repeatedly tried to force their way in, and castigated those who dared to enter, calling them “Nazis,” “Hitlers,” and “damned fascists.” An overmatched contingent of about 70 police officers escorted speakers and attendees into the building while vainly trying to maintain order. Angry protesters tore people’s clothing and hurled vegetables, rocks, bottles, and stench bombs, breaking more than two dozen windows and injuring three officers.

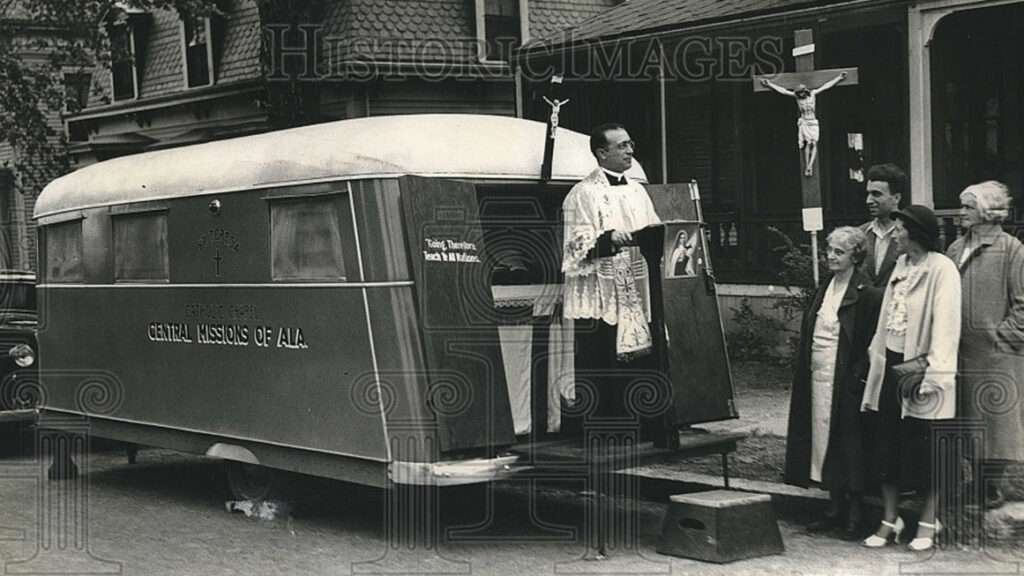

The riot resulted in 19 arrests, though most of the charges were later dismissed. One charge that stuck: Terminiello, a suspended Catholic priest from Alabama who was advertised as “the Father Coughlin of the South,” was charged with “breach of the peace”—a species of “disorderly conduct.” A municipal court jury convicted him of that offense two months later, and he was fined $100, equivalent to about $1,700 today. Terminiello, who argued that he was being punished for constitutionally protected speech, unsuccessfully challenged his conviction in the First District Appellate Court and the Illinois Supreme Court.

Terminiello had more luck with the U.S. Supreme Court, which in May 1949 ruled that the Chicago ordinance under which he had been convicted, as construed by the trial court, was inconsistent with the First Amendment. Municipal Court Judge John McCormick had instructed the jury that “misbehavior may constitute a breach of the peace if it stirs the public to anger, invites dispute, brings about a condition of unrest, or creates a disturbance, or if it molests the inhabitants in the enjoyment of peace and quiet by arousing alarm.” That construction, the Supreme Court said, was plainly at odds with freedom of speech.

“A function of free speech under our system of government is to invite dispute,” Justice William O. Douglas wrote for the majority in Terminiello v. Chicago. “It may indeed best serve its high purpose when it induces a condition of unrest, creates dissatisfaction with conditions as they are, or even stirs people to anger. Speech is often provocative and challenging. It may strike at prejudices and preconceptions and have profound unsettling effects as it presses for acceptance of an idea. That is why freedom of speech, though not absolute, is nevertheless protected against censorship or punishment, unless shown likely to produce a clear and present danger of a serious substantive evil that rises far above public inconvenience, annoyance, or unrest. There is no room under our Constitution for a more restrictive view.”

Douglas’ ringing defense of free speech against the heckler’s veto still echoes today. His observations are relevant when student protesters disrupt speeches by people whose views they abhor or when such events are canceled by university administrators worried about the unrest they might provoke. Douglas’ insistence that speech must be tolerated even if it results in bitter disagreement is likewise salient when issues such as police brutality, immigration, and Israel’s war with Hamas provoke protests and counter-protests in the streets or on campuses. But Terminiello is also remembered for a dissent that took a less accommodating view of free speech.

Justice Robert H. Jackson, who had previously served as solicitor general, attorney general, and the chief U.S. prosecutor at the Nuremberg trials of Nazi war criminals, thought Douglas and the four colleagues who joined his opinion were out of their minds. Like many Americans today, Jackson perceived a country on the precipice of chaos, with right-wing and left-wing extremists staging deliberately provocative demonstrations aimed at overturning democracy. Drawing an analogy to the violent clashes that set the stage for Adolf Hitler’s ascendance, he argued that the majority’s understanding of the First Amendment was a potentially lethal threat to democracy, freedom, and peaceful coexistence.

“This Court has gone far toward accepting the doctrine that civil liberty means the removal of all restraints from these crowds and that all local attempts to maintain order are impairments of the liberty of the citizen,” Jackson complained. “The choice is not between order and liberty. It is between liberty with order and anarchy without either. There is danger that, if the Court does not temper its doctrinaire logic with a little practical wisdom, it will convert the constitutional Bill of Rights into a suicide pact.”

In the decades since, that formulation has taken on a life of its own, cited as a justification for expanding government power and restricting individual freedom in situations far afield from the original case. The continuing influence of the “suicide pact” meme in legal and political debates is remarkable for two reasons. First, Jackson was expressing a view that the Supreme Court has emphatically and repeatedly rejected. Second, his concluding admonition was a rhetorical flourish, not a logical argument. Confusing the two invites shortcuts that sacrifice liberty on the altar of order.

‘Slimy Scum’

The size of Terminiello’s audience rivaled that of the mob outside. “Persons desiring to hear defendant speak filled the 800-seat auditorium to capacity,” the Illinois Supreme Court noted, while “others stood in the rear and about 250 were turned away.” Some people who were unsympathetic to Terminiello’s message gained entry via admission cards they had obtained from acquaintances—a fact to which he alluded at the beginning of his speech.

“I suppose there are some of the scum got in by mistake, so I want to tell a story about the scum,” Terminiello said. “Nothing that I would say can begin to express the contempt I have for that howling mob on the outside…and nothing I could say tonight could begin to express the contempt I have for the slimy scum that got in by mistake.”

Terminiello warned that “the tide is changing, and if you and I turn and run from that tide, we will all be drowned in this tidal wave of communism which is going over the world.” In Russia, he said, “from 8 to 15 million people were murdered in cold blood by their own countrymen, and millions more through Eastern Europe at the close of the war are being murdered by these murderous Russians, hurt, being raped, and sent into slavery. That is what they want for you, that howling mob outside.”

Terminiello’s animosity was not limited to Russians. He averred that Henry Morgenthau, who as secretary of the treasury during the Roosevelt administration was the first Jew in the presidential line of succession, had a “plan for the starvation of little babies and pregnant women in Germany.” He also claimed that Jewish military doctors serving in Europe made it a practice to amputate the arms of German men “so they never could carry a gun” and that Jewish nurses would “inject diseases in them.”

Terminiello called upon his audience to oppose “every attempt to shed American blood to promote Zionism in America.” He inveighed against “atheistic, communistic Jewish or Zionist Jews.” (The Jewish Jews are the worst!) “We must not lock ourselves up in an upper room for fear of the Jews,” Terminiello declared. He clarified that he was referring to “the Communistic Zionistic Jew, and those are not American Jews.” Then he added: “We don’t want them here; we want them to go back where they came from.”

Wrapping up his speech, Terminiello delivered a mixed message about how his audience should deal with the protesters outside. “They are being led,” he said. “There will be violence. That is why I say to you, men, don’t do it. Walk out of here dignified. The police will protect you. We will not be tolerant of that mob out there. We are not going to be tolerant any longer. We are strong enough. We are not going to be tolerant of their smears any longer. We are going to stand up and dare them to smear us. We are not going to be tolerant any longer of their pagan eye-for-an-eye philosophy.”

During Terminiello’s trial, the reaction to his speech was a matter of dispute. Testimony by defense witnesses, the Chicago Tribune reported, “tended to show that no remark made by [the speakers] caused any disturbance or commotion in the hall, but that all the riotous disorder occurred outside the hall and was incited by hundreds of pickets.” As the Illinois Supreme Court later put it, those witnesses “testified that the audience was quiet, attentive and orderly at all times.” The city’s witnesses told a different story.

‘Dirty Kikes’

Terminiello’s chief accuser was Ira Latimer, who at the time was a Communist but later turned against the party and its ideology, eventually serving as executive vice president of the American Federation of Small Businesses. In 1946, Latimer was executive secretary of the Chicago Civil Liberties Committee, which seemed like a misnomer given his role in the case against Terminiello. After unsuccessfully seeking a permit to hold a protest outside the auditorium during Smith’s rally, Latimer attended the event, using tickets he said he had received in the mail. He was so disturbed by what he heard, he said, that he filed a complaint against Terminiello.

“The comments from the audience when the statement was made about the non-Christian doctors and nurses were ‘Ah’ and ‘Oh’ and other expressions of anger,” Latimer testified. “A man in back of us said that the Jews and niggers and Catholics would have to be gotten rid of….There were howls, hoots, cries, and shouts at various points in the speech….They were not calm. They were disturbed and angry.”

Other witnesses backed up that account. “When Terminiello said there was no crime too great for the Jews to commit,” reported Lucille McVicker Lipman, a self-described Quaker of Irish heritage, “the woman next to me said, ‘Yes, the Jews are all killers, murderers. If we don’t kill them first, they will kill us.'” When Terminiello talked about amputations by Jewish doctors and injections of syphilis by Jewish nurses, Lipman testified, “The people around me said ‘Oh, isn’t that terrible’ and ‘That is a terrible thing’ and ‘Oh’ and ‘Ah.'” On cross-examination, Lipman recalled that she was “very much riled up at all the lies that were told.” Although “nothing that Father Terminiello said caused me to do anything violent or against the law,” she said, “I felt like it.”

When Terminiello “said that the Zionistic Jews are threatening to undermine our country and should all be sent back to Russia where they came from,” testified another witness, a Jewish man named Michael Karel, “everybody started to holler, ‘Yes, send the Jews back to Russia. Kill the Jews….Dirty kikes.'” When Terminiello talked about amputations, Karel reported, “Right next to me several women hollered, ‘They ought to do that to the Jews. They ought to cripple them.'” When Terminiello described Morgenthau’s purported plan to starve German children, Karel testified, “The audience said ‘They ought to starve the Jews’ and ‘They ought to kill Morgenthau.'”

According to Karel, not everyone believed what Terminiello was saying. At one point, he recalled, one member of the audience stood up and shouted, “You are a God damned liar.”

Terminiello’s speech, in other words, made people angry, either at the Jews or at Terminiello himself. Was that properly treated as a legal offense?

A.A. Pantelis, the city attorney who made the case against Terminiello, thought so. “Freedom of speech must have due regard for the feelings of others,” he argued. “Free speech does not mean you can go out and lie about people, or call people names, or call people ‘scum.’ Terminiello’s speech that night was nothing but abuse, misstatements, vilification, and slander.”

The Illinois Supreme Court agreed. It said Terminiello’s “epithets directed to certain members of the audience” (i.e., “the slimy scum that got in by mistake”) were “derisive, fighting words likely to cause a breach of the peace by the addressee, words whose publication constitutes a breach of the peace by the speaker.” When an audience member called Terminiello “a God damned liar,” the court added, that represented “an actual breach of the peace within the auditorium.” Lipman’s report that she “was very wrought up and felt like committing violence” was “further evidence” of Terminiello’s guilt. As for “the majority of the audience,” Terminiello’s “provocative and inflammatory utterances instilled in them the fear of revolution, domination and murder by what he described as the criminal Jewish element in America and, more particularly, by the mob outside the auditorium.”

The evidence, the court concluded, “amply supports plaintiff’s assertion that Terminiello aroused his audience to a feverish feeling of anger and hatred.” It rejected “the false impression that great constitutional questions are involved and sacred constitutional rights are jeopardized.” Chicago’s ordinance “is a common one and does not violate constitutional rights,” the court said. “Freedom of speech is not license. The constitution does not absolve one from punishment for the unlawful nature and consequences of his speech.”

Fighting Words

Jackson took a similar view of the matter. He conceded that the First Amendment protects controversial speech, even by enemies of liberal democracy. But he said that does not absolve speakers of the legal responsibility to avoid inflaming their opponents in situations where a violent response is likely. “The local court that tried Terminiello was not indulging in theory,” he wrote. “It was dealing with a riot and with a speech that provoked a hostile mob and incited a friendly one, and threatened violence between the two.”

Just seven years earlier in Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire, Jackson noted, the Supreme Court had recognized a First Amendment exception for “fighting words”—”those which by their very utterance inflict injury or tend to incite an immediate breach of the peace.” That unanimous decision, which was joined by Douglas and three of the four justices who agreed with him in Terminiello, involved a Jehovah’s Witness, Walter Chaplinsky, who attracted a hostile crowd while passing out literature and condemning the “racket” of organized religion on a sidewalk in Rochester, New Hampshire.

When a heckler tried to punch Chaplinsky, the town marshal, James Bowering Jr., warned the preacher that he was asking for trouble, then left the scene. After several men assaulted Chaplinsky, a traffic officer, rather than trying to disperse the crowd, took him into custody and began escorting him to the police station. On the way, as the officer and several members of the crowd insulted Chaplinsky and his religion, Chaplinsky again encountered Bowering, who reiterated his earlier warning and, according to Chaplinsky, cursed at him. In response, Chaplinsky condemned Bowering as a “damned racketeer” and “damned fascist.”

Chaplinsky was convicted of violating a New Hampshire statute that made it illegal to address another person in public with “any offensive, derisive or annoying word” or “call him by any offensive or derisive name.” The trial judge read that law as applying only to words tending to cause a breach of the peace. So construed, the Supreme Court said, the law was consistent with the First Amendment.

The Illinois Supreme Court’s ruling against Terminiello invoked Chaplinsky, and the “fighting words” doctrine figured prominently in the arguments before the U.S. Supreme Court. But the Court’s decision dodged that issue, instead emphasizing the breadth of McCormick’s jury instruction. Jackson and the other dissenters objected to that maneuver, noting that Terminiello had not challenged the instruction and that the Illinois appeals courts had not considered the issue.

In hindsight, Terminiello may have been the beginning of the end for the “fighting words” doctrine, which the Supreme Court declined to apply in that case and never again invoked to uphold a prosecution. But as Belmont University law professor David Hudson noted in a 2022 essay on the 80th anniversary of Chaplinsky, “the concept remains part of First Amendment law and has been used by many lower courts to uphold convictions for breach of the peace or disorderly conduct.”

By contrast, the Supreme Court has explicitly repudiated the “clear and present danger” test to which Douglas alluded in Terminiello. A unanimous Court applied that test in the 1919 case Schenck v. United States, which upheld the Espionage Act convictions of two Socialist Party leaders who had distributed antidraft flyers during World War I. The justices ditched the “clear and present danger” standard half a century later in Brandenburg v. Ohio, which involved racist and antisemitic public remarks by a Ku Klux Klan leader who raised the possibility of “revengeance.”

In that case, the Court unanimously overturned Clarence Brandenburg’s conviction for violating an Ohio statute that made it illegal to advocate “crime, sabotage, violence, or unlawful methods of terrorism as a means of accomplishing industrial or political reform.” Under Brandenburg, even advocacy of illegal conduct is constitutionally protected unless it is both “directed” at inciting “imminent lawless action” and “likely” to do so.

Even under the pre-Brandenburg test, Douglas did not think Terminiello’s conduct posed a “clear and present danger.” It is not hard to see why. Although Jackson cited the violent protest that accompanied Terminiello’s speech as a reason to punish him, the riot was already underway before he opened his mouth. Jackson himself made that point during oral argument in the case. “The disorder started before the speech was made,” he noted. “Does a man have to cancel a speech because he anticipates antagonism?” Jackson pressed the point. “Was there any greater disorder after the speech than before?” he asked Chicago’s lawyer, L. Louis Karton. “No,” Karton conceded.

The rioters, in other words, were reacting to a speech that had not happened yet, a speech they probably could not hear even after Terminiello got started. Yet if there had been no riot, it seems clear, Terminiello would not have been arrested for delivering hateful remarks inside a private auditorium to people who voluntarily came to hear him.

Even as he issued a warrant for Terminiello’s arrest, Municipal Judge Samuel Heller remarked on the Chicago Police Department’s failure to maintain order. “This is a hell of a way to protect the city,” he said. “I’m one of the suckers who have to pay taxes.”

The “anarchy” that Jackson feared does not flow inexorably from speech that “stirs the public to anger, invites dispute, brings about a condition of unrest, or creates a disturbance.” It happens only when people respond to words with violence. People who act on that impulse should be punished. They should not be rewarded by restrictions on the speech that offends them.

‘Justice Jackson’s Well-Known Words’

Although Jackson lost that battle, his “suicide pact” formulation proved enduringly appealing. Chief Justice Fred Vinson, one of the Terminiello dissenters, cited Jackson’s warning the following year in American Communications Association v. Douds, which upheld the Taft-Hartley Act’s requirement that union leaders file affidavits with the National Labor Relations Board affirming they were not members of the Communist Party and did not support the violent overthrow of the U.S. government.

The phrase came up again in the 1963 case Kennedy v. Mendoza-Martinez. “While the Constitution protects against invasions of individual rights, it is not a suicide pact,” Justice Arthur Goldberg wrote in the majority opinion. Unlike Vinson, he did not cite Jackson, and he did not rule in the government’s favor. Although “the powers of Congress to require military service for the common defense are broad and far-reaching,” he concluded, a law that stripped draft evaders of their citizenship went too far. Goldberg used “suicide pact” in similar fashion the following year in Aptheker v. Secretary of State, quoting himself in a decision that rejected a law barring Communist Party members from obtaining U.S. passports.

Chief Justice Warren Burger, in yet another passport case, joined Goldberg in attributing the “suicide pact” line to Goldberg rather than Jackson. But Burger’s majority opinion in the 1981 case Haig v. Agee, which said it was OK to revoke the passport of a former CIA agent who had started spilling secrets, was more in the spirit of Jackson’s pro-government Terminiello dissent.

Justice Stephen Breyer’s dissent in the 2017 case Ziglar v. Abbasi restored credit for the line to Jackson but used it the way Goldberg had, defending constitutional rights while acknowledging their limits. The majority rejected damage claims by illegal immigrants who said they had been mistreated when they were detained in the wake of the September 11 attacks by Al Qaeda. “In Justice Jackson’s well-known words,” Breyer wrote, “the Constitution is not ‘a suicide pact.'” He nevertheless thought the plaintiffs should be allowed to pursue their claims.

As that case reflects, the post-9/11 war on terror prompted a proliferation of “suicide pact” references. Politicians and commentators invoked the phrase in defense of policies such as expanded surveillance, speech restrictions, the detention of American citizens as “enemy combatants,” trial by military tribunals, and torture. The prolific legal scholar Richard Posner, then a judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 7th Circuit, published a whole book on this theme in 2006. In Not a Suicide Pact, Posner advocated “a more flexible, practical approach” to constitutional interpretation that allows restrictions on civil liberties in response to the “sui generis” threat posed by international terrorism.

Jackson’s warning also has figured in the gun control debate. “The Constitution’s a sacred document, but it is not a suicide pact,” Sen. Lindsey Graham (R–S.C.) said in 2016, voicing support for banning gun possession by people on “no fly” lists. “This is not hard for me. Due process is important, but at the end of the day, we are at war.” Three years later, Graham used a similar line in defense of “red flag” laws, which authorize court orders that suspend the gun rights of people deemed a threat to themselves or others. “The Second Amendment’s important to me,” he told The State, “but it’s not a suicide pact.”

After the 2022 mass shooting at an elementary school in Uvalde, Texas, Rep. Mary Gay Scanlon (D–Pa.) was one of many legislators who reupped Democratic demands for new gun restrictions. “The Second Amendment is not unlimited,” she said, “and it is not a suicide pact.” Calling for stricter gun control in 2023, California Gov. Gavin Newsom worried that “the Second Amendment is becoming a suicide pact.” That same year, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit quoted Jackson’s Terminiello dissent while rejecting a challenge to the Trump administration’s unilateral ban on bump stocks. Defending federal gun charges against Hunter Biden in 2024, Special Counsel David Weiss agreed with Graham, Scanlon, Newsom, and the D.C. Circuit that “the Second Amendment…is not a suicide pact.”

‘Jackson Had the Answer’

Other examples show how versatile Jackson’s line can be. In a 1996 CNN debate, conservative lawyer Bruce Fein defended indefinite civil commitment of sex offenders after they have completed their sentences. “I think Justice Robert Jackson had the answer,” he said. “The Bill of Rights is not a suicide pact.” The U.S. Court of Appeals for the 3rd Circuit alluded to Jackson’s point in a 2011 case involving a deadly police shooting, saying “police officers do not enter into a suicide pact when they take an oath to uphold the Constitution.”

The debate over COVID-19 policies inspired similar rhetoric. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit invoked Jackson’s Terminiello dissent when it rejected a challenge to California’s ban on in-person religious services in 2020. So did two Rutgers University policy fellows when they defended New Jersey’s similar restrictions in a Newark Star-Ledger op-ed piece later that year, arguing that the government “can restrict behavior to serve the common good.” In 2021, a CNN opinion piece urged mandatory COVID-19 vaccination, saying “the Constitution is not a suicide pact guaranteeing a right to harm others.”

Sometimes the cliché comes up in situations closer to the original context. In 1990, New Criterion publisher Samuel Lipman defended obscenity charges against a Cincinnati art museum that had exhibited Robert Mapplethorpe’s photographs. “At the Supreme Court,” Lipman said on The MacNeil/Lehrer NewsHour, “I would hope that the justices responsible would perhaps take into account Justice Jackson’s decision [sic] in the Terminiello case that the Bill of Rights is not a suicide pact, that there are some things which governments must do to survive and societies must do to protect themselves.”

In 1997, George Hacker, director of alcohol policy studies at the Center for Science in the Public Interest, portrayed the wine industry’s attempts to publicize research on the potential health benefits of moderate drinking as a similarly grave threat. “The First Amendment is not a suicide pact,” Hacker told the San Francisco Chronicle. “It’s not appropriate for the wine industry to play surgeon general in this country, using half-truths and misleading information.”

In a 1999 Washington Times opinion piece, conservative commentator David Stolinsky objected to the Supreme Court’s conclusion that flag burning is a form of constitutionally protected expression. “As has been said, the Constitution is not a suicide pact,” Stolinsky wrote. “It does not require that we remove all respect for national traditions and symbols from our public life.”

Three years later, New York Times columnist Nicholas Kristof recommended censorship of books that include recipes for biological or chemical weapons. “Do we as a nation really want to permit books that facilitate terrorism and mass murder?” Kristof wrote. “As Justice Arthur Goldberg declared in a 1963 Supreme Court case, the Constitution ‘is not a suicide pact.'”

In a 2023 Time essay, University of Michigan law professor Barbara McQuade defended a gag order against Donald Trump in his federal election interference case. She closed by citing Goldberg’s opinion in Aptheker: “As the Supreme Court has said, the Constitution is not a suicide pact.” In a 2024 New York Times essay, Columbia law professor Tim Wu warned that “the First Amendment is spinning out of control.” He bemoaned Supreme Court decisions extending constitutional protection to speech “regardless of its value,” including “outright lies,” and to opinions expressed by people organized as corporations. To reinforce his complaint, Wu quoted Jackson’s Terminiello dissent.

A Trump Card

In retrospect, Jackson’s fear that stopping Chicago from fining Terminiello was the first step on the road to national suicide seems overwrought. It is even harder to take seriously the idea that tolerating Mapplethorpe’s photographs, pro-wine propaganda, flag burning, or speech that offends Wu could spell the end of the republic.

These purported exercises in suicide prevention are naked attempts to justify censorship by absurdly inflating a supposed danger and appealing to the authority of a renowned jurist. And even when speech restrictions might be justified, as with the gag order against Trump, a persuasive defense requires reasoned argument, as opposed to intimations of imminent doom. Inveighing against suicide pacts adds nothing to the logical or legal case for any particular policy.

That goes double when the conversation extends to subjects that have nothing to do with Terminiello. It goes without saying, for example, that efforts to prevent terrorism are aimed at saving lives. The same is true of disease control policies and gun regulations. That obvious observation tells us nothing about the effectiveness, let alone the constitutionality, of any specific measure.

The logical irrelevance of Jackson’s admonition is plain in cases where courts duly note it but then proceed to reject its pro-government implications, as Goldberg did in Mendoza-Martinez and Aptheker. Even Posner, who favored a “flexible” approach to civil liberties in the war on terror, did not view the imperative to avoid suicide pacts as an open-ended license for all interventions aimed at protecting public safety. In 1999, he authored a 7th Circuit opinion that rejected anticrime checkpoints in Indianapolis, deeming them inconsistent with the Fourth Amendment. “The Constitution is not a suicide pact,” he wrote. “But no such urgency has been shown here.”

Usually, however, people who say “the Constitution is not a suicide pact” view that statement as a trump card. This policy might be unconstitutional, they implicitly concede, but we should pursue it anyway because the stakes are too high to follow “doctrinaire logic” rather than “practical wisdom.” That way of thinking is tantamount to saying that civil liberties should be respected only when it’s convenient, which would be suicide of a different sort.

The post ‘The Constitution Is Not a Suicide Pact’ appeared first on Reason.com.