Unlike most sectors, edtech has been booming over the last few months. Flashcards startup Quizlet is now a unicorn, digital textbook company Top Hat is finding unprecedented surges in usage and student success business Edsights raised nearly $2 million from high-profile investors, all from inbound interest. Investors are so confident that homeschooling might become a trend that they just invested $3.7 million in Primer, which creates a “full-stack infrastructure” to help parents get started.

But as tired parents juggle work, family and sanity all day, nearly every day, they say edtech is not a remedy for all education gaps right now.

Parents across all income groups are struggling with homeschooling.

“Our mental health is like whack-a-mole,” said Lisa Walker, the vice president of brand and corporate marketing at Fuze. Walker, who lives in Boston but has relocated to Vermont for the pandemic, has two kids, ages 10 and 13. “One person is having a good day. One person is having a bad day, and we’re just going throughout the family to see who needs help.”

Socioeconomically disadvantaged families have it even worse because resources are strapped and parents often have to work multiple jobs to afford food to put on the table.

One major issue for parents is balancing a decrease in live learning with an uptick in “do it at your own pace” learning.

Walker says she is frustrated by the limited amount of live interaction that her 10-year-old has with teachers and classmates each day. Once the one hour of live learning is done, the rest of the school day looks like him sitting in front of a computer. Think pre-recorded videos, followed up by an online quiz, capped with doing homework on a Google doc.

Asynchronous learning is complicated because, while it is not interactive, it is more inclusive of all socioeconomic backgrounds, Walker said. If all learning material is pre-recorded, households that have more kids than computers are less stressed to make the 8 a.m. science class, and can fit in lessons by taking turns.

“Even though I know there’s a lot of video fatigue out there, I would love there to be more live learning,” Walker said. “Tech is both part of the problem and part of the solution.”

TraLiza King, a single mother living in Atlanta who works full time as a senior tax manager for PWC, points out the downside of live video instruction when it comes to working with younger children.

One challenge is overseeing her four-year-old’s Zoom calls. King needs to be available to help her daughter, Zoe, use the platform, which isn’t intuitive for kids at that age. She helps Zoe log on and off and mute when appropriate so instruction can go on interrupted, ironically enough.

Her 18-year-old college freshman could supervise the four-year-old’s learning, but King doesn’t want her older daughter to feel responsible for teaching. It leaves King to play the role of Zoom tech support, and teacher, in addition to mom and full-time employee.

“This has been a double-edged sword; there’s beauty in it that I get to see what my girls are learning and be a part of their everyday,” she said. “But I am not a preschool teacher.”

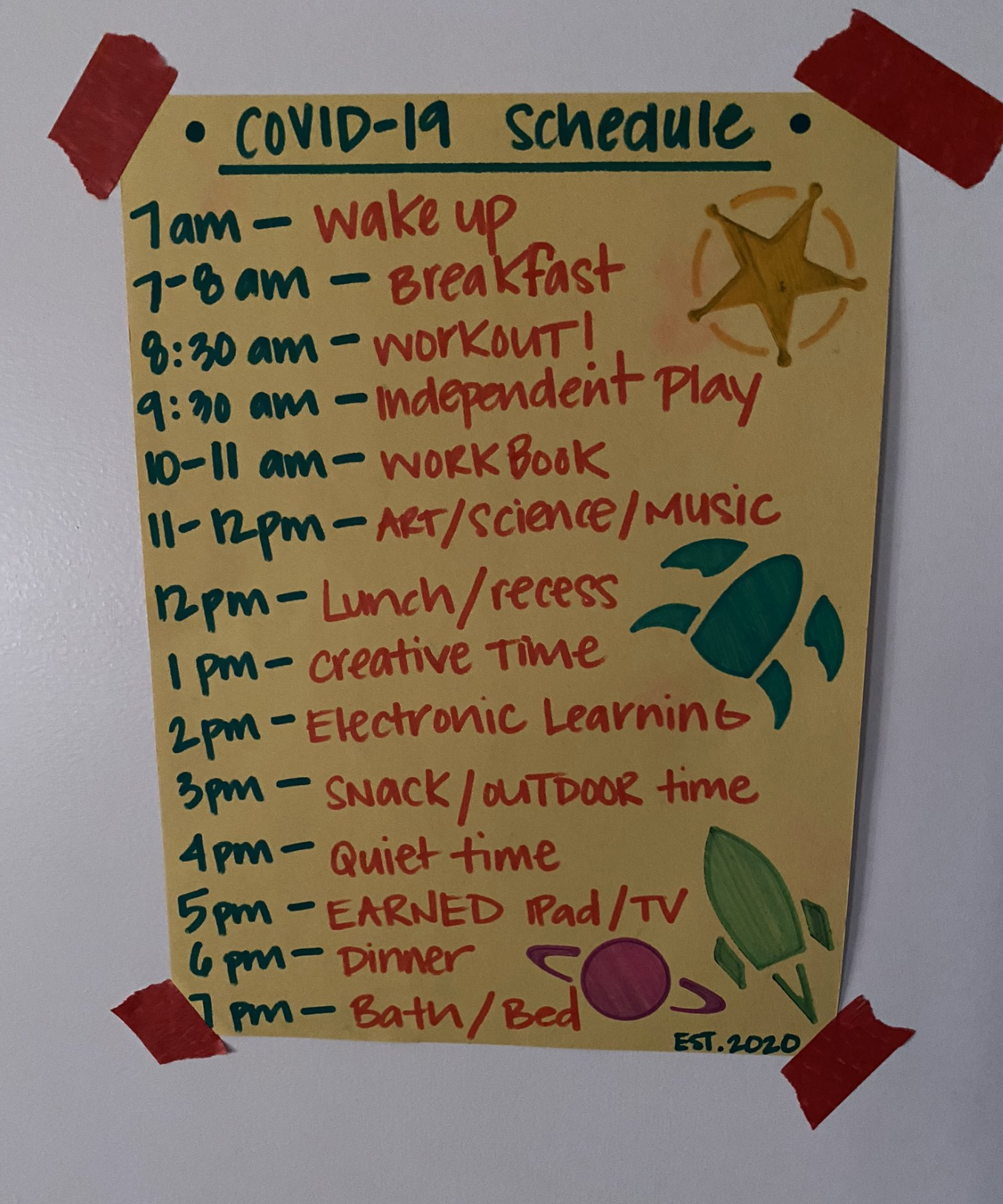

Some parents are finding success in pretending it is business as normal. The moment that Roger Roman, the founder of Los Angeles-based Rythm Labs, and his wife saw that there was a shutdown, they scrambled to create a schedule for the children. Breakfast at 6 a.m., physical education right after, and then workbook time and homework time. If their five-year-old checks all the boxes, he can “earn” 30 minutes of screen time.

The Roman family’s schedule for their child.

Technology definitely helps. Roman says he relies on a few apps like Khan Academy Kids and Leapfrog to give him some time to take work calls or meetings. But he says those have been more like supplements instead of replacements. In fact, he says one big solution he found is a bit more low-tech.

“Printers have been a godsend,” he said

The kids being at home has also given the Roman family an opportunity to address the racial violence and police brutality in our country. The existing school curriculums around history have been scrutinized for lacking a comprehensive and accurate account of slavery and Black leaders. Now, with parents at home, those disparities are even more clear. Depending on the household, the gaps around education on slavery can either inspire a difficult conversation on inequality in the country, or leave the talk tabled for schools to reopen.

Roman says he doesn’t remember a time where he wasn’t aware of racism and injustice, and assumes the same will be true for his sons.

What’s next for remote learning?

In light of the struggles parents and educators alike are seeing with the current set of online learning tools and their inability to inspire young learners, new edtech startups are thinking about how the future of remote learning might look.

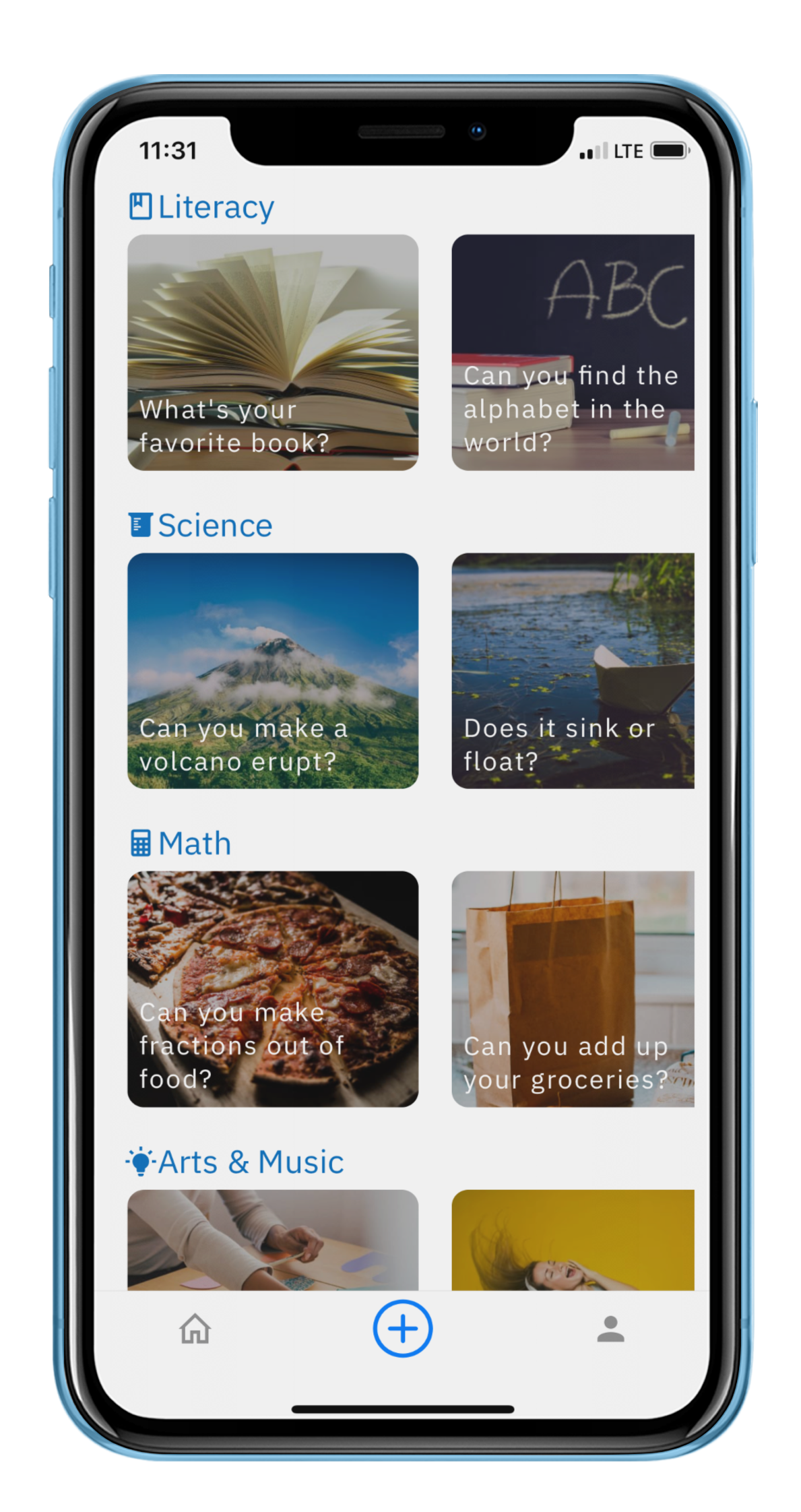

Zak Ringelstein, the co-founder of Zigazoo, is launching a platform he describes as a “TikTok for kids.” The app is for children from preschool to middle school, and invites users to post short-form videos in response to project-based prompts. Exercises could look like science experiments — like building a baking soda volcano or recreating the solar system from household items — and the app is controlled by parents.

The first users are Ringlestein’s kids. He says they became disengaged with learning when it was just blind staring at screens, leading him to conclude that interaction is key. Down the road, Zigazoo plans to forge partnerships with entertainment companies to have characters act as “brand ambassadors” and feature in the short-form video content. Think “Sesame Street” characters starting a TikTok trend to help kids learn what photosynthesis is all about.

A preview of Zigazoo, a “TikTok for kids” and its video-based prompts“As an educator, I’ve been surprised at how little content exists for parents that is not just entertaining but is actually educational,” he said.

Lingumi is a platform that teaches toddlers critical skills, like learning English. The company began because preschool classes are packed with so many students that teachers can’t give one on one feedback during the “sponge-like years.” Lingumi uses another startup, SoapBox, and its voice tech to listen and understand children, assess how they are pronouncing words and judge fluency.

“Edtech products were designed to work in the classroom and a teacher was supposed to be in the mix somewhere,” said Dr. Patricia Scanlon, the CEO of SoapBox. “Now, the teacher can’t be with the kids individually and this is a technology that gives updates on children’s progress.”

Another app, Make Music Count, was started by Marcus Blackwell to help students use a digital keyboard to solve math equations. It serves 50,000 students in more than 200 schools, and recently landed a partnership with Cartoon Network and Motown records to use content as lessons for followers. If you log onto the app, you are presented with a math problem that, once solved, tells you which key to play. Once you solve all the math problems in the set, the keys you played line up to play popular songs from artists like Ariana Grande and Rihanna.

The app is using a well-known strategy called gamification to engage its younger users. Gamification of learning has long been effective in engaging and contextualizing studies for students, especially younger ones. Add a sense of accomplishment, like a song or a final product, and kids get the positive feedback they’re looking for. The strategy is found in the underpinnings of some of the most successful education companies we see today, from Quizlet to Duolingo.

But in Make Music Count’s case, it’s forgoing gamification’s usual trappings, like points, badges and other in-app rewards to instead deliver something far more fun than virtual items: music that kids enjoy and often seek out on their own.

Gamification, much like technology more broadly, is not all-encompassing of the deeply personal and hands-on aspects of school. Yet that is what parents need right now. We’re left with a reminder that technology can only help so much in a remote-only world, and that education has always been more than just comprehension and test-taking.

The missing piece to edtech: School isn’t just learning, it’s childcare

At the end of the day, if the future of work is remote, parents will need more support with childcare assistants. Some startups trying to help that include Cleo, a parenting benefits startup that recently partnered with on-demand childcare service UrbanSitter.

“As working moms desperate for a solution to the crisis facing parents today, we were focused on developing a solution that didn’t just work for our members and enterprise clients, but also one that we’d use ourselves. After experimenting and trying everything from virtual care to scheduling shifts to looking for new caregivers ourselves, we realized the only solution that would work for families would require a new model of childcare designed for the unique issues COVID-19 has created,” Cleo CEO Sarahjane Sacchetti told TechCrunch in May.

Sara Mauskopf, the co-founder of childcare marketplace Winnie, said that tech companies trying to help remote learning need to remember that “it’s not just the education aspect that has to be solved for.”

“School is a form of childcare,” she said.

“The thing that irks me is that I see these tweets all the time that ‘more people are going to homeschool than ever before,” Mauskopf said. “But no one is going to feed my toddler mac and cheese or change their diaper.”

Powered by WPeMatico