“I see no reason,” the late Sen. Harry Reid (D–Nev.) once declared on the Senate floor, “why those in this country who enjoy drinking tea need someone else to tell them what tastes good.”

Yet for nearly 100 years that is exactly what the government did, thanks to one of the strangest agencies ever to be a part of the federal bureaucracy.

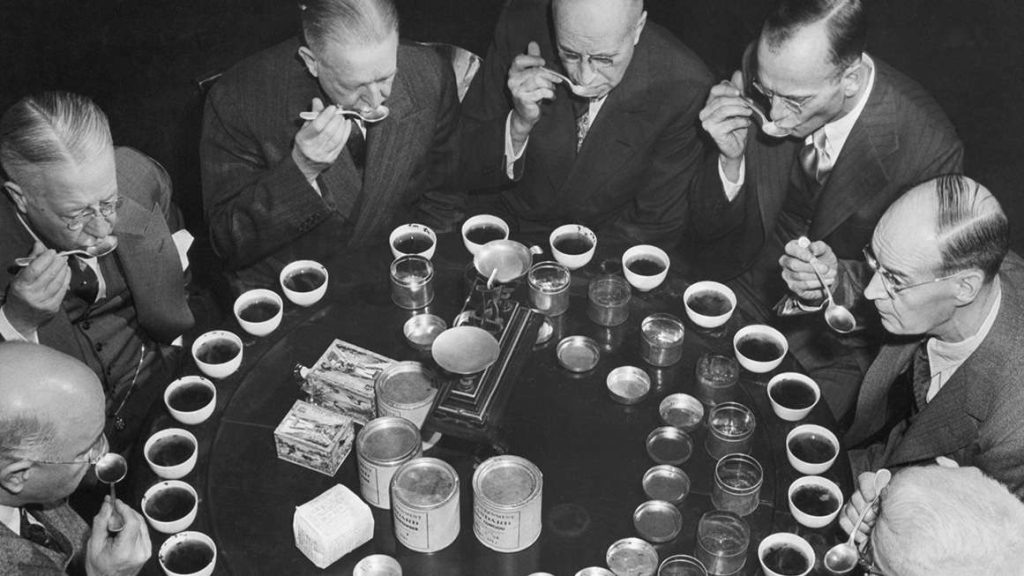

In addition to the usual beverage regulations aimed at ensuring proper storage and safe handling, imported tea was required for decades to pass a literal taste test before it could be sold in the United States. The task fell to a group of Food and Drug Administration (FDA) appointees, who would gather annually in a converted Navy warehouse in Brooklyn to smell, slosh, sip, and spit the various oolongs, greens, and Earl Greys that tea merchants sought to sell to Americans.

This was the federal Board of Tea Experts.

The board’s members would taste dozens of teas over the course of several days. The process was more an art than a science. According to a 1989 Washington Post profile, there was no uniform method for tasting. Some board members worked in silence while others slurped their tea or gargled it loudly. Some preferred to taste the tea hot; others let it cool first. The warehouse where they gathered was outfitted with pictures of old-timey sailing ships, a kitchen sink, several kettles for boiling water, boxes upon boxes of tea, and large windows. The board’s then-leader Robert H. Dick told the Post thatto properly inspect the tea, “I have to have a north light.”

When Reid voiced his objection to the tea board in 1995, the agency had already survived two decades’ worth of efforts to shut it down. Congress finally ended the board’s oversight of tea imports a year later, but the federal Board of Tea Experts technically still existed for another 27 years. It was officially terminated on September 19, 2023.

The bizarre history and surprising longevity of the federal tea-tasting board is something of a mixed bag for anyone who wants to see more federal programs iced for good.

On one hand: The board was eventually shut down.

On the other: If it takes nearly 50 years to get rid of something as useless and insignificant as the Board of Tea Experts, what hope can there possibly be to do away with larger governmental entities backed by more powerful special interests? Hardly an election season goes by without some (usually Republican) presidential hopefuls promising to abolish this department or that agency—the Department of Education and the Environmental Protection Agency are perennial favorites. Are those efforts doomed before they begin? Will those promises always be empty?

The weird tale of the Board of Tea Experts holds a variety of lessons for anyone interested in shrinking the size and scope of government. It’s a warning about the stickiness of bad ideas, about an inertia that can limit even the smallest attempts at trimming the state.

“This is the reason people are upset about government,” Reid said in that 1995 Senate floor speech. “What an absolute waste of taxpayers’ money is it to have them spend $200,000 a year swishing tea around in their mouths.”

A Tea Board Is Born

Anthropologists believe human beings were drinking tea before recorded history. In China, where tea was first cultivated, accounts of the drink’s benefits for keeping healthy and staying awake date back at least as far as the Shang dynasty (founded around 1700 B.C.); physical evidence of tea consumption and the tea trade goes back well over 2,000 years.

The relationship between tea and the state is ancient too. According to one Chinese legend, the drink was invented when leaves were accidentally blown into a cup belonging to Emperor Shennong, who was fond of sipping boiled water. The resulting brew tasted good, and presumably gave the mythic ruler one of humanity’s first caffeine highs.

Tea made its way to Europe (and then the Americas) in the 1600s. A 1657 listing from a London coffee shop offered tea for sale starting at 16 shillings per pound—roughly $190 per pound today. Governments all over the world tried to subsidize and monopolize the tea trade at various times, and many collected bountiful revenue from their citizens’ and colonists’ addictions.

In the New World, that quest for revenue helped spark a history-altering backlash. The uprising in Boston Harbor on the night of December 16, 1773, wasn’t the first tax revolt in American history, and it wouldn’t be the last. But it remains the most memorable, and a crucial part of the country’s founding mythology. The lingering cultural memory of the Boston Tea Party might have even played an indirect role in the creation of the federal Board of Tea Experts more than a century later.

“Since the British drank a lot of tea, they would pick the best teas, and then a lot of times when they had something they didn’t want, that was left over, or maybe even damaged or something, they would fill the order from the United States with some of that tea,” Dick, whose tenure on the Board of Tea Experts lasted from 1947 until 1996, explained in a 1984 interview published as part of an internal history of the FDA.

Worried that British tea exporters were taking advantage of their less sophisticated American customers, Congress passed the Tea Importation Act of 1897. The act created a new federal commission charged with ensuring the quality of the nation’s tea supplies. But from the start, the board’s standards seem to have been quite open to interpretation. When the Tea Importation Act was first passed, it merely said “that the tea should be rejected if it was unfit,” Dick explained in that interview. “Well, unfit meant different things to different people.”

Over time, tasting standards for different types of tea were put into place. Imported tea had to match the federally approved flavor profiles to be legally sold, with the tasters responsible for setting the standards. After the FDA was created in 1906, the tea-tasting board was rolled into the new agency, which would eventually grow to regulate cosmetics, pharmaceuticals, and, of course, food. But the Board of Tea Experts remained a unique element of the FDA’s sprawling portfolio. “Tea is the only food or beverage for which the [FDA] samples every lot upon entry for comparison to a standard recommended by a federal board,” noted a 1996 analysis from the House of Representatives.

As the Post detailed in its 1989 profile, the annual gathering of the tea-tasters was not meant to identify the best teas or set particularly high standards for what would be allowed into the country. Rather, “the task is to select the worst that are still drinkable” and then use those standards as the basis for what would be permitted to enter the country for the rest of the year. At the height of its vague yet absolute powers, the tea board employed testers based in Boston, New York, and San Francisco; their job was to translate the board’s standards into practice. A separate but related entity, the Board of Tea Appeals, provided due process for anyone wronged by the tea-tasters’ opinions.

Even with some standards in place, bureaucratic laziness sometimes prevailed. At one point, Dick recalls being told by a then-senior member of the board that “you don’t need to look at all of those teas because you can look at the prices and you can tell which is the good tea and which is the bad tea.” Too bad consumers couldn’t be trusted to do the same.

If the board was protecting consumers, it doesn’t seem to have been protecting them from much—the board rejected less than 1 percent of the teas submitted for approval each year. But Dick argued the mere threatof rejection was a protection.

“If you eliminate the Tea Act then you’ve got a case of where somebody is going to take chances,” Dick said in 1984. “If they have a poor tea, they don’t know whether it will be rejected or not, and they don’t know whether it would be sampled or not, and they may be tempted to ship it. So, it would make a difference.”

There is a long history of domestic industries using made-up or exaggerated concerns about consumer safety to seek political power, then using that power to limit competition or create cartels. It’s tempting to project that narrative onto the history of the Board of Tea Experts.

But there’s a problem with that theory, says Ryan Young, a senior economist at the pro-market Competitive Enterprise Institute. There was not much of a domestic tea production industry in the 1890s. Even today, the vast majority of tea consumed in the United States comes from abroad, primarily India and China.

There may have been legitimate reasons to worry about the quality of tea being imported into the U.S. at the time the board was created, says Young. But it was private industry, not government, that solved it.

“Back then, groceries were often sold out of crates and barrels, often with no way to know who the producer was or where the product came from,” he says. “Brands are an extremely important self-regulation device in markets. They improve trust and accountability, whereas anonymous producers can get away with all sorts of shenanigans.”

By the middle of the 20th century, private self-regulation had solved the problem that the Board of Tea Experts was supposed to fix.

But government programs don’t just go away when they become obsolete.

Alexander J. Grille, chairman of the Board of Tea Experts, 1961 (Getty)

The Long, Slow Death of the Tea Board

Can drinking tea help you live longer? Some studies suggest as much. Research published in Advances in Nutrition in 2020 found that regular consumption of tea is correlated with a lower risk of death from various cardiovascular issues, including strokes. The study’s authors attributed tea drinkers’ longer life spans to “flavonoids”—a pigment found in many tea leaves that is thought to be a powerful antioxidant.

I know of no peer-reviewed study suggesting government bureaucracies tasked with tea tasting have longer than average life spans. But the available evidence suggests that, indeed, they are quite difficult to kill.

“These tea-tasting people are just like lizards,” Sen. Reid declared in 1995, comparing the board to critters he said he’d catch as a kid, ones whose tails would grow back even after they were yanked off. “You grab them and jerk something off and they are right back.”

By then, the Board of Tea Experts had survived more than a quarter-century with a target on its back.

The first attempt to eliminate the tea board occurred in 1970, when the Nixon administration tried to redirect the board’s budget of $125,000 (almost $1 million today) to other parts of the FDA. Nixon was looking for an easy public relations coup, according to a contemporary New York Times report. Killing off the tea-tasting board would be a symbol of the federal government’s commitment to belt tightening, or so he thought.

The tea industry fought for the board’s survival, arguing that the president had no power to drain the board’s budget unless Congress first repealed the 1897 law that authorized it. With Congress apparently uninterested, Nixon quietly surrendered.

The attempt at least provided one lasting moment of hilarity. While digging through boxes of documents at the Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum in 2021, Ashton Merck, a postdoctoral researcher at North Carolina State University, came across a letter ostensibly mailed from a dormitory at the University of California, Berkeley. The letter writer claimed to represent a group of individuals who were “appalled at [Nixon’s] proposal to eliminate one of the few remaining bastions of tradition and culture in this country” and the planned liquidation of Dick’s job as the only full-time employee of the board.

The name of this alleged group taking the time to bend the ear of the most powerful man in the world? “The Committee To Keep Dick Tasting.”

In the ensuing years, the tea-tasting board routinely turned up on lists put together by groups like Taxpayers for Common Sense as a target for federal budgetary pruning. Presidents Jimmy Carter and Ronald Reagan both made half-hearted attempts to kill the board, without success.

In the ’90s, Congress finally organized a serious revolt against the board’s existence. Reid, an unexpected advocate for shrinking government, took on the role of Sam Adams. In a 1993 speech supporting his bill to cut off funding for the tea-tasting board’s expense reimbursements, including a $50 per diem for each member, Reid reached for the obvious metaphor. A “congressional tea party” was necessary, he said, to “dump the tea experts overboard.”

The bill passed. But even after losing their per diems and expenses, the board simply poured another cup.

Two years later, Reid aimed to bag the board for good. Working across the aisle with Sen. Hank Brown (R–Colo.), Reid pushed through a proposal to cut off all taxpayer funding for the board’s staff. But that provision was struck from the final version of the bill during a conference committee meeting, following what The Washington Post termed “last-minute lobbying” from the industry.

“It’s a sign of how difficult it is in Washington,” Brown told The New York Times in September 1995. “Defeating some of this nonsense is going to be a long tough job. The tea board is quite resilient.”

At that point, Reid boiled over. No longer content merely to pull the metaphorical tails off the tea bureaucrats, Reid and Rep. Scott Klug (R–Wis.) drafted bills to repeal the Tea Importation Act of 1897 and abolish the Board of Tea Experts for good. The bill passed both chambers of Congress unanimously and was signed into law by President Bill Clinton on April 9, 1996.

The Board of Tea Experts had boiled its last kettle. Or so it appeared. Technically, the tea-tasting board outlived the man who played the biggest role in killing it. Reid died in late 2021, after a long Senate career that culminated in an eight-year stint as majority leader (during which time he battled a congressional Tea Party of a different kind).

Fifteen months after Reid passed away, the federal Board of Tea Experts was finally gone for good—after existing in a sort of limbo for more than two decades in which it had no members and no budget. Its obituary: a brief September 2023 notice in the Federal Register, which records the doings of the executive branch agencies, announcing that the FDA was removing “the Board of Tea Experts from the Agency’s list of standing advisory committees” in accordance with the law passed by Congress in 1996—yes, 27 years prior.

Time To Kill

A lot of things happened in American politics during the two and a half decades that the Board of Tea Experts existed in a sort of bureaucratic limbo. One of the more amusing moments took place on a debate stage in Michigan on November 9, 2011, where Gov. Rick Perry of Texas had a political moment for ages.

“And I will tell you, it’s three agencies of government when I get there that are gone: Commerce, Education, and the, uh, what’s the third one there? Let’s see,” the presidential hopeful said, awkwardly trying to recall what he wanted to tell you.

This was near the peak of the GOP’s Tea Party era—a small-government populist movement that recalled that other, more famous story about the intersection of tea and American politics—and the candidates vying for a chance to challenge President Barack Obama were competing to see who could make the most aggressive promise to slash government.

“You can’t name the third one?” asked moderator John Harwood, incredulously. The crowd laughed. Other candidates shouted suggestions. But it was hopeless. “The third one. I can’t. Sorry,” Perry concluded, before meekly adding, “Oops.”

Perry’s campaign limped along a little while after the remark, but for all intents and purposes, that was the moment it ended. It was a moment that mattered not only because of the comedy of a polished politician coming unglued on national television, but because it highlighted the humongous gap between Perry’s campaign-trail blather and the reality of governing. How could anyone believe he had a workable plan to close entire federal departments when he couldn’t even remember his own talking points?

A few years later, then-President Donald Trump appointed Perry to run the Department of Energy—the same department Perry couldn’t remember he wanted to abolish.

With the annual federal budget deficit now nearing $2 trillion and the national debt reaching unsustainable levels, it’s important for politicians to have big goals for cutting government. But ambition means nothing if not backed up with a practical plan of action. That’s the difference between Nixon’s failed attempt at killing the Board of Tea Experts as a public relations maneuver and Reid’s serious, yearslong effort that finally buried it.

Trying to tear down old programs that no longer make sense—if they ever did—also cuts against the natural tendency of most politicians.

“Every new president and committee chair wants to make a mark, and so they push to create new programs of their design,” says Chris Edwards, a budget policy expert at the Cato Institute. “They don’t bother trying to repeal the related old and outdated programs because that would use major political capital they would rather use creating new programs.”

The Board of Tea Experts is not the only federal agency or program to be successfully closed or privatized. Edwards points to the Office of Technology Assessment, an internal congressional study committee that produced reports on a wide range of scientific and technological issues for about 20 years before being shuttered in 1995 for being duplicative and unnecessary.

But the vast majority of the traffic is moving in the opposite direction. According to Downsizing the Federal Government, a Cato-affiliated project that Edwards runs to track the sprawling size of the federal government, there were 2,418 grant or subsidy programs on the books this year, more than double the number that existed in 1990.

That’s why the best time to plan to close regulatory bodies and other government agencies isn’t when they become obviously unnecessary—it’s when they are created.

At first, every government agency has some reason for existing, even if it’s not a good one. Even the Board of Tea Experts, which was rooted in those late–19th century worries about Americans being served subpar tea. Once it’s created, regulators and their rules warp markets and create constituencies that benefit from preventing change—including the regulators themselves.

In the mid-1980s, Dick was arguing for the tea board’s continued relevance by pointing to potential consumer harms that were no longer realistic in a world with grocery stores and extensive private quality-control operations. Nearly 30 years after the Board of Tea Experts was effectively shuttered, there’s no indication that Americans are drinking worse tea—because the board and its standards weren’t accomplishing anything the market hadn’t already sorted out decades ago. And, of course, the FDA still holds the power to regulate tea (as it regulates all food and drink in the United States), even in the absence of a special board tasked with sipping each imported batch.

Is there a way to ensure programs and agencies that have outlived their usefulness are actually shut down? Young of the Competitive Enterprise Institute points to Texas. The state’s Sunset Advisory Commission, which periodically reviews government agencies and recommends to the state Legislature when one is no longer serving a purpose, claims to have played a role in abolishing 41 agencies, consolidating another 51, and saving taxpayers more than $1 billion.

With mandatory sunsets, Young says, “ineffective or unneeded agencies can still shut down, even if Congress can’t muster up the courage for a vote.”

Absent some kind of institutional reform, federal programs only seem to end up on the chopping block when they make an enemy of someone in a powerful position. Without Reid, the Board of Tea Experts might very well be holding its annual tasting session right now.

When any changes do happen on their own, they tend to be incredibly slow.

In October, the Prune Administrative Committee—a federal entity that oversees the “handling of dried prunes”—took the first step toward abolishing itself after an internal review found that the costs of the board’s regulations “outweigh the benefits to industry members.”

But it isn’t going away for good just yet. No, the committee will continue to exist for at least another seven years, during which time it will issue no rules or regulations. If America survives that wild experiment with ungoverned dried plums, the committee and its parent, the U.S. Department of Agriculture, will decide whether to make the arrangement permanent.

“Inertia might be the strongest force in all of politics,” says Young. “If it takes 50 years of reform efforts to close down a tea-tasting board, then larger reforms are doomed without some kind of institution-level change

More Wasteful Than the Tea Board?

The Board of Tea Experts was a uniquely silly and superfluous part of the federal bureaucracy. No other product has ever been subjected to literal taste testing by federal officials before it could be legally sold.

Sadly, it is not the only silly or superfluous part of the government. A comprehensive list of pointless and wasteful government programs would be too long to print, but here are six others begging to meet the same fate as the tea board.

(Photos: iStock)

Popcorn Board: Created by Congress to “develop new markets for popcorn and popcorn products.” The board funds itself by charging fees to popcorn producers—fees that presumably are passed along to popcorn eaters. Maybe that’s why it’s so expensive at the movie theater? Similar user fee–funded boards include the National Fluid Milk Processor Promotion Board, the National Mango Board, the National Potato Promotion Board, and the National Watermelon Promotion Board.

Mushroom Council: They say no one wants to see how the sausage of government gets made, but what about the shit it’s grown in? A part of the Department of Agriculture (USDA), the Mushroom Council is supposed to “maintain and expand existing mushroom markets and uses.” Imported mushrooms are taxed 0.0055 cents per pound to pay for that critical work.

Denali Commission: Created in 1998 to fund infrastructure projects in Alaska, the Denali Commission was targeted for elimination by both Barack Obama and Donald Trump—but Congress keeps funding it anyway. Mike Marsh, the commission’s inspector general, wrote in 2013 that the agency is “a congressional experiment that hasn’t worked out in practice” and urged Congress to “put its money elsewhere.” In FY 2023, the Denali Commission had a budget of $13.8 million.

Christmas Tree Promotion Board: A 12-member board (one for each day of Christmas?) created in 2011 to “expand the market and uses of fresh-cut Christmas trees” and funded with a new fee of 15 cents on all real Christmas trees sold in the country. Nothing says “Merry Christmas!” like a new tax on the people who are already using your product. Interestingly, this was not created by an act of Congress but by the USDA’s Agricultural Marketing Service, which Congress authorized in 1996 and gave the ability to create new boards and agencies like this one. Oh, administrative state, how lovely are thy line items.

Corporation for Travel Promotion: Established in 2010, this 11-member board within the Department of Commerce is charged with “providing useful information to those interested in traveling to the United States,” as if there weren’t already dozens of websites and tour books doing the same thing. It’s now known as Brand USA. Foreigners seeking visas to enter the United States pay a $4 fee to fund the corporation, even though they likely don’t need to be convinced to visit.

Rural Utilities Service: The Rural Electrification Administration was created as part of the New Deal in 1936 to expand the nation’s power grids and phone lines to far-flung homes and communities. These days it’s pretty difficult to find homes that lack electricity or phone service, but the administration is still around (though it was renamed in 1994). This tiny corner of the USDA—yep, it’s not even part of the Energy Department—cost taxpayers $154 million this year.

The post After a Century, the Federal Tea Board Is Finally Dead appeared first on Reason.com.