Around 2 a.m. on Monday, December 6, 1875, a “posse of police” led by Captain William Douglass descended on 609 Dupont Street in San Francisco. The cops arrested Fannie Whitmore, Cora Martinez, James Dennison, and Charles Anderson, along with “two Chinamen who kept the place.”

That place, The San Francisco Examiner explained, was an “opium den,” and this was the first raid conducted under an ordinance that the city’s Board of Supervisors had enacted on November 15. The new law decreed that “no person shall, in the city and county of San Francisco, keep or maintain, or become an inmate of, or visit, or shall in any way contribute to the support of any place, house, or room, where opium is smoked, or where persons assemble for the purpose of smoking opium.”

The supervisors made that crime a misdemeanor punishable by a fine of $50 to $500—roughly 3 percent to 30 percent of a clerk’s annual salary in California at the time. Violators also could be jailed for 10 days to six months.

The four patrons and two proprietors nabbed by Douglass and his crew were convicted the same day and paid the minimum fine, so you could say they got off lightly. Then again, it must have been jarring to be hauled off to court for conduct that had been perfectly legal a few weeks before. And the sweeping scope of the city’s ban, which on its face reached not only commercial establishments but also any private residence “where opium is smoked,” was pretty startling too.

San Francisco’s ordinance applied only to opium smoking, not to oral consumption of the same drug, which had long been widely available in over-the-counter patent medicines. Nor did it cover injections of morphine, an opium derivative. That was not an oversight. The law was designed to target a habit associated with a despised minority—a habit that alarmed police, politicians, and the press precisely because it was associated with a despised minority.

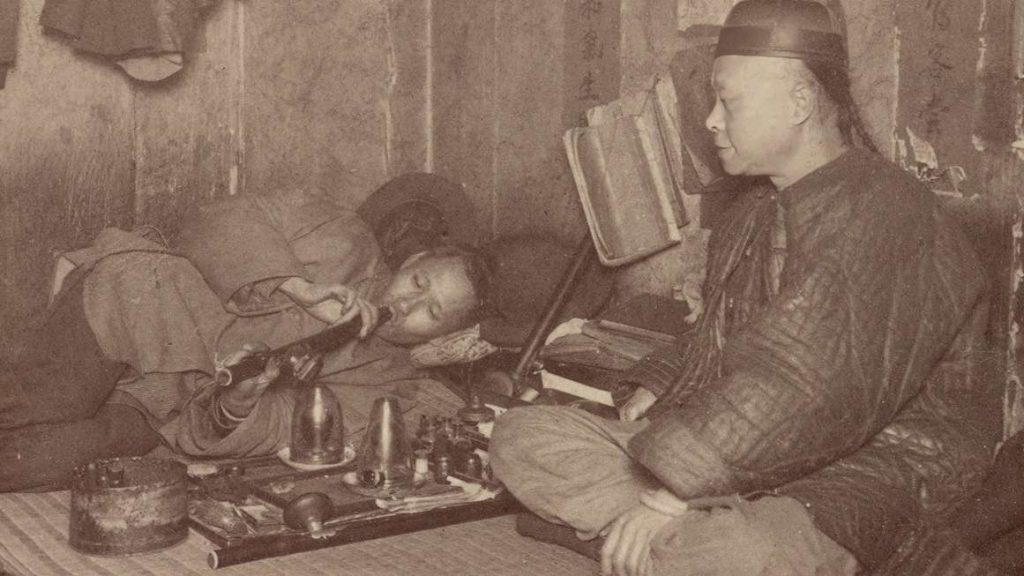

That habit, the Board of Supervisors worried, was spreading to the European-American majority. As the board’s Health and Police Committee explained, “opium-smoking establishments kept by the Chinese” were serving “white men and women.” These places were “patronized not only by the vicious and the depraved” but “are nightly resorted to by young men and women of respectable parentage and by young men engaged in respectable business avocations.”

The committee was aghast that “habitués of these infamous resorts inhale the fumes from the opium pipes until a state of stupefaction is produced.” And “unless this most dangerous species of dissipation can be stopped in its inception,” it warned, “there is great danger that it will become one of the prevalent vices of the city.” These “infamous resorts” were “an unmitigated evil,” demanding “immediate and rigid legislation.”

That “rigid legislation” was the nation’s first anti-drug law, if you don’t count the short-lived alcohol bans that 13 states enacted in the mid-19th century. It presaged many other laws, some much more draconian, that aimed to stamp out politically disfavored methods of intoxication. It also established a pattern that would be repeated with cocaine and marijuana, which likewise inspired fear at least partly because they were perceived as drugs favored by menacing out-groups.

“The most passionate support for legal prohibition of narcotics has been associated with fear of a given drug’s effect on a specific minority,” David F. Musto concluded in The American Disease, his classic 1973 drug policy history. “Certain drugs were dreaded because they seemed to undermine essential social restrictions which kept these groups under control.” As with opium smoking in San Francisco, those drugs also were dreaded as vectors of contamination that could transmit to the majority the debauchery, dissipation, and degradation that political leaders saw as characteristic of those minorities.

‘The Worst Class of People’

Testifying before the California Senate’s Special Committee on Chinese Immigration the year after Douglass’ raid, another San Francisco police officer, George W. Duffield, averred that “ninety-nine Chinamen out of one hundred smoke opium” and that “every house” had an opium den. That sounded like an excuse for cops to invade any home in Chinatown. Duffield, who described Chinese immigrants as “the worst class of people on the face of the earth,” probably would have been fine with that.

In a report submitted to the committee on behalf of the San Francisco Police Department, another officer, James R. Rogers, echoed the concerns that had driven the Board of Supervisors to action. “This habit had formerly been practiced by the Chinese almost exclusively,” he said. But in recent years, “not less than eight places have been started, furnished with opium pipes, beds for sleeping off the fumes, etc.” Although “these latter places were conducted by Chinamen,” they were “patronized by both white men and white women, who visited these dens at all hours of the day and night.”

This was a common and persistent complaint. A decade after Rogers’ testimony, state Sen. John Lenahan (D–San Francisco) warned that Chinese residents of his city, “all” of whom seemed to “indulge in the vice,” were “diligent in the induction of others into the accursed habit.” Opium dens were “everywhere,” he said, and “we are assured that white men, women, boys and girls are continually made victims of the deadly drug.”

Wasn’t San Francisco’s ban supposed to put an end to that? Despite the 1875 ordinance, Rogers reported in 1876, “the practice, deeply rooted, still continues.” And “in enforcing the law with regard to this matter,” police “have found white women and Chinamen side by side under the effects of this drug—a humiliating sight to any one who has anything left of manhood.” That comment reflected anxieties about opium-fostered race mixing, including the fear that Chinese men were using the drug to seduce or sexually enslave white women.

“Within the walls of an opium den all fiends are equal,” The San Francisco Examiner complained in 1889. “Colored men and white women lie about the floors, inhaling the fumes of the drug until, stupefied, they fall into the opium-smokers’ sleep. The majority of loose women who ply their trade on the streets in the southern section of the city have been brought to their degraded condition by the use of opium, or by association with users of it.” Five years later, the Examiner was appalled at “the horrible condition of the opium-depravity” in Salt Lake City, as illustrated by a raid in which “two white women were found lying on the floor completely under the influence of the drug, and almost in a nude state.”

In his 1890 book How the Other Half Lives, muckraking journalist Jacob Riis described a house in New York City’s “Chinese quarter” inhabited by “women, all white, girls hardly yet grown to womanhood, worshipping nothing save the pipe that has enslaved them body and soul.” Riis was disturbed by their equanimity: “Of the depth of their fall no one is more thoroughly aware than these girls themselves; no one is less concerned about it. The calmness with which they discuss it, while insisting illogically upon the fiction of a marriage that deceives no one, is disheartening.”

The American Federation of Labor (AFL), making the case against Chinese immigration in 1902, described “little girls no older than 12” who “were found in Chinese laundries under the influence of opium.” Through “some wily method,” the AFL said, “they have been induced by the Chinese to use the drug,” and “what other crimes were committed in those dark and fetid places when these little innocent victims of the Chinamen’s wiles were under the influence of the drug are almost too horrible to imagine.”

While Riis reported that “scrupulous neatness” was “the distinguishing mark of Chinatown,” the California Senate’s immigration committee said the opposite was true in San Francisco, describing Chinese homes as “filthy in the extreme.” If it weren’t for “the healthfulness of our climate,” the committee theorized, “our city populations would have long since been decimated by pestilence from these causes.”

A committee member, state Sen. Edward J. Lewis (D–Colusa), elaborated on his disgust at life in Chinatown. “We went into places so filthy and dirty that I cannot see how these people live there,” he reported. “The fumes of opium, mingled with the odor arising from filth and dirt, made rather a sickening feeling creep over us.” Since “the whole Chinese quarter is miserably filthy,” he added, “the passage of an ordinance removing them from the city, as a nuisance, would be justifiable.”

As politicians like Lewis saw it, the opium problem was inextricably intertwined with the Chinese problem. If the government could not forcibly remove these “filthy” foreigners, as Lewis seemed to prefer, it could at least make life as difficult as possible for them. As former congressman James Budd put it at an 1885 anti-Chinese meeting in Stockton, California, it was local authorities’ “duty” to make conditions so “devilishly uncomfortable” that the Chinese would be “glad to leave.”

Legislators certainly tried. San Francisco’s ban on opium dens, which cities like Stockton imitated, was just one facet of a broad, longrunning legal campaign aimed at subjugating or driving away Chinese immigrants. In addition to attempts at outright bans on Chinese immigration into California, that campaign included special taxes, discriminatory regulations, and restrictions on the right to hunt, fish, own land, vote, and testify in court.

These measures were prompted by large-scale Chinese immigration to the United States, which began during the California Gold Rush in the 1850s. The immigrants were overwhelmingly men, many of whom worked in California’s mines and, later, on the transcontinental railroad. From 1860 to 1880, the Chinese-American population rose from about 35,000 to more than 100,000. That was still less than 1 percent of the total U.S. population, but the vast majority of the immigrants settled in California, where they accounted for 9 percent of the population and perhaps a quarter of workers. Many white Californians were alarmed by this alien presence.

‘A Human Tidal Wave’

From the beginning, the influx of Chinese immigrants aroused resentment and hostility, including attacks on Chinese miners by native prospectors. In 1850, the California Legislature imposed a $20 monthly tax (about a fifth of a laborer’s wages) on foreign miners, which was later reduced but also amended so that it applied only to Chinese immigrants. Eight years later, the Legislature approved “An Act to Prevent the Further Immigration of Chinese or Mongolians to This State,” which the California Supreme Court deemed unconstitutional.

The court also rejected an 1862 law imposing a special monthly tax on residents from China who were not already subject to the miner’s tax. Legislators were explicit about their goals, calling the bill “An Act to Protect Free White Labor Against Competition With Chinese Coolie Labor, and to Discourage the Immigration of the Chinese Into the State of California.” As the justices saw it, those legislators were trying to exercise powers that the U.S. Constitution assigned to the federal government: the imposition of import duties and regulation of commerce with foreign nations.

Economic developments stoked the anti-Chinese sentiment reflected in such laws. The Gold Rush was over by the end of the 1850s, and the Pacific Railroad was completed in 1869. The “Long Depression” of the 1870s added to anxieties about economic competition from Chinese immigrants while simultaneously driving them toward trades and small businesses previously dominated by white Californians.

The complaints about Chinese competition, which were amplified by labor unions, the Workingmen’s Party of California (founded in 1877), and middle-class businessmen, turned virtues—thrift and a strong work ethic—into vices. Anti-Chinese agitators groused that the immigrants were willing to work hard for less pay because they kept their living expenses low, subsisting on meager diets and tolerating the crowded conditions decried by state legislators. Although that complaint was hard to reconcile with the portrayal of Chinese immigrants as indolent opium addicts, nativists were unfazed by the inconsistency.

On a Sunday in April 1876, the San Francisco Chronicle filled its front page with an article about the “Chinese Problem” that weaved these contradictory themes together. “Celestials,” it said, were prone to opium smoking, gambling, prostitution, and “other vices.” But they were also hardworking and entrepreneurial, creating “a human tidal wave” of “disastrous competition” for “our miners, mechanics, and even tradesmen.” They had opened laundries, cigar shops, “small ware” stores, and vegetable stands. These “peculiar people” had “quaint and curious” customs, and they were experts at “economizing space,” combining “ingenuity and industry” with “the vices and abominations of the Chinese character.” They had no “higher ambition than that of hoarding money.”

The Chronicle devoted a section of the article to “the opium dens of San Francisco,” which it said “probably number several hundred.” In contrast with the claims of cops like Duffield and politicians like Lenahan, the paper allowed that “the practice of opium-smoking among the Chinese” was “perhaps not universal” but said it nevertheless “prevails to an alarming extent.”

The article, which described opium’s subjective effects as “delicious and entrancing,” also cast doubt on the distinction that the city’s Board of Supervisors had drawn between modes of consumption. “The use of opium in this form does not appear to produce the baneful results arising from eating the drug,” it said. “Nor is there any danger of fatal result, as from overdosing with morphine.” In fact, the paper said, “opium-smoking may be regarded as simply a new—perhaps an improved—form of drunkenness.” Unlike alcohol consumption, the Chronicle reported, opium smoking “develops no fighting [or] destructive impulses,” and it is “a slower system of poisoning than the use of alcoholic stimulants.”

Despite those qualifications, the Chronicle‘s dismay at this possibly “improved” form of intoxication was unmistakable. The opium dens “patronized by the lower classes defy description,” the paper said, but gave it a go anyway: “Imagine a room less than fifteen feet square, with a ceiling about eight feet high. In this room on the four sides are arranged three tiers of bunks, the heads against the walls. Here opium-smoking accommodations are furnished for forty persons. The only method of ventilation is through the door, and this is often closed and fastened. The fumes of burning opium, the stench and impurities arising from this huddled nest of human beings, and the suffocating properties of the atmosphere, ought certainly to kill any decent human being in an hour, but it seems to have only a pickling effect on the Chinaman.”

The implication that Chinese immigrants were not decent human beings was spelled out in the same paragraph. “If anything were needed to complete the degradation of the Mongolian race,” the Chronicle said, “the besotting effects of this pernicious practice furnishes [sic] the ‘lower deep’ beyond which moral and physical debasement cannot possibly go.” Worse, that practice had attracted “American men and women,” who “not infrequently are found in a state of complete insensibility” after “pulling away together at the pipe.”

The Chronicle saw opium smoking as emblematic of a broader problem: Chinese immigrants were unassimilable. While “the emigrants to our shores from every other quarter of the globe in time become naturalized citizens,” the paper complained, “a Chinaman never takes the slightest interest in anything pertaining to the public good or the national sentiment.”

‘This Moral Crusade’

What was to be done? Rather incongruously, given its scathing criticisms, the Chronicle cautioned against “intemperate language” and “threatening conduct,” which might lead to “violence” that would discredit the anti-Chinese movement. This was a realistic concern in light of the violence California already had witnessed, including an 1871 Los Angeles riot in which hundreds of men looted Chinatown and murdered 19 residents.

“We must so conduct this moral crusade against further emigration of these hordes that the whole world will approve and applaud,” the Chronicle said. “The mechanics and laboring men of California and the Pacific coast cannot afford to admit squarely that the only question involved in this movement is one of competition and of dollars and cents. There is a moral and social aspect to the matter more important than any other.”

The “moral crusade” championed by the Chronicle soon inspired the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, the first federal law to ban immigration based on national origin. The law, which applied to “skilled and unskilled laborers,” notionally made exceptions for certain categories of visitors, but permission was difficult to obtain. Congress also made Chinese immigrants already living in the United States ineligible for citizenship and required them to obtain reentry permits when they traveled abroad. Such policies were applauded by the “Anti-Chinese Leagues” that began to proliferate across the West in the late 19th century.

Other anti-Chinese measures of this era were neutral on their face but clearly aimed at a specific ethnic group. San Francisco, for example, set a minimum space requirement of 500 cubic feet per resident for private dwellings (thereby forbidding common living conditions in Chinatown), prohibited theater performances between midnight and 6 a.m. (targeting Chinese opera), and required licenses for laundries in wooden buildings—licenses that Chinese laundry owners somehow were never able to obtain. That last ordinance passed muster with the California Supreme Court, which saw it as a valid exercise of the city’s police power. But the U.S. Supreme Court later unanimously ruled that the law’s discriminatory enforcement violated the 14th Amendment’s guarantee of equal protection.

San Francisco’s ban on opium dens fell into the same category as the housing, theater, and laundry regulations. It was ostensibly motivated by public health and safety concerns but actually designed to discomfit unwelcome foreigners. Western cities and states followed San Francisco’s example, which provoked additional court challenges.

In 1886, a federal judge in Oregon upheld a Chinese man’s conviction under a state law banning the sale of opium for nonmedical use. “Smoking opium is not our vice,” U.S. District Judge Matthew Deady wrote, “and therefore it may be that this legislation proceeds more from a desire to vex and annoy the ‘Heathen Chinee’ in this respect, than to protect the people from the evil habit. But the motives of legislators cannot be the subject of judicial investigation for the purpose of affecting the validity of their acts.”

The following year, by contrast, the California Supreme Court blocked enforcement of a Stockton ordinance that made it a crime for two or more people to gather for the purpose of smoking opium. In the majority opinion, Justice Jackson Temple remarked on the law’s intrusiveness.

“To prohibit vice is not ordinarily considered within the police power of the state,” Temple wrote. “A crime is a trespass upon some right, public or private. The object of the police power is to protect rights from the assaults of others, not to banish sin from the world or to make men moral….Such legislation is very rare in this country. There seems to be an instinctive and universal feeling that this is a dangerous province to enter upon, and that through such laws individual liberty might be very much abridged.” Concurring Justice A. Van R. Paterson likewise argued that “every man has the right to eat, drink, and smoke what he pleases in his own house without police interference.”

The court conceded that the secondary effects of personal habits such as opium smoking “may justify the [state] legislature in declaring these vices to be crimes.” But it concluded that local governments lacked such authority under California’s constitution.

State legislators would soon do what the California Supreme Court said cities could not. Six years before the justices nixed Stockton’s opium ordinance, California already had made it a misdemeanor to maintain “any place” where opium is “sold or given away to be smoked at such place.” The state criminalized all nonmedical opium sales in 1907 and made possession illegal in 1909, the same year that Congress banned the importation of opium for smoking.

‘Half-Baked Legislation’

Aside from import taxes, the Smoking Opium Exclusion Act of 1909 was the first federal law aimed at preventing deliberate consumption of a psychoactive substance. Like the San Francisco ordinance that inaugurated the anti-opium campaign, it targeted a habit that was seen as alien to American culture. While it prohibited importation of “opium prepared for smoking,” it expressly allowed importation of opium “for medicinal purposes.”

That exception covered the traditional American use of opium and its derivatives, which consumers could buy over the counter during the 19th and early 20th centuries. Patent medicines, which were promoted as remedies for a wide range of symptoms and illnesses, often included ingredients that today can be legally obtained only by prescription. Brands containing opium or morphine included Perry Davis’ Painkiller, Mrs. Winslow’s Soothing Syrup, and Ayer’s Cherry Pectoral. The prevalence of opiates in legal products sold “for medicinal purposes” was reflected in a law that Congress approved three years before it took up the Smoking Opium Exclusion Act. The Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906 required that patent medicines “bear a statement on the label” indicating the “quantity or proportion” of 10 specified drugs, including opium, morphine, heroin, cannabis, cocaine, and alcohol.

That law, which was meant to give consumers information and prevent the sale of “adulterated or misbranded or poisonous” products, did not require a doctor’s prescription to purchase remedies containing the listed drugs, although states had begun to do that. Nor did the 1906 law address the sale of opium itself. The Smoking Opium Exclusion Act aimed to fill that gap.

Sen. Henry Cabot Lodge (R–Mass.) and other supporters of the bill said its passage was urgent in light of the International Opium Commission then meeting in Shanghai. The U.S. government, which was flexing its influence by taking a leading role in international drug control, had instigated the conference and was keen to demonstrate its seriousness by enacting federal legislation. Lodge emphasized that the State Department “is extremely anxious that this legislation shall be passed as soon as possible.”

Members of Congress took heed. The Senate approved the bill that very day, and the House of Representatives followed suit less than a week later. Although legislators were united in viewing opium smoking as an evil that should be stamped out if possible, there was some disagreement about the effectiveness and constitutionality of the proposed law. But even the objections made it clear which drug users Congress had in mind.

Although “Chinamen desire opium prepared for smoking in their own country,” Rep. Sereno E. Payne (R–N.Y.) said, smokable opium “can be manufactured in this country from medicinal opium.” And “rather than not have it at all,” he added, “they would take that prepared in this country, undoubtedly.” Given that prospect, Payne was skeptical that the law would have a substantial impact on opium smoking.

Rep. Joseph H. Gaines (R–W.Va.), who called the bill “a piece of half-baked legislation,” took a similar view. “Because of the conservatism of the Chinese people,” he said, “they so much prefer to have their opium prepared in China that the high rate of duty has not stimulated the manufacture of opium in this country.” But “those who are addicted to the opium habit will secure the drug in some form, even though not the preferred form.” Instead of “protecting the morals of the country,” Gaines thought, the import ban would “stimulate the manufacture and preparation of opium for smoking in this country.”

Payne eventually came around. After conferring with the secretary of state, he said he was “very cheerfully for this bill,” having been persuaded that it would “tend in some manner to make it more difficult and therefore to suppress in part the use of smoking opium.” But Gaines, while emphasizing that he was “yielding to no man…in my hostility to the practice of opium smoking and in my hostility to the drug habit generally,” remained opposed.

“It takes plenary power to stamp out such a habit—if it can be suppressed at all—the full police power,” Gaines said. “Our federal government does not have it.” Although he thought “a prohibitive internal-revenue tax on the transportation of opium for smoking” might make the import ban more effective, he was not sanguine about the prospects of eradicating the habit through legislation. “It must occur to every man that if a thing which is so desirable to be done as stamping out the smoking of opium could be done by a simple law prohibiting the importation of opium,” he said, “that remedy would have been thought out and applied long ago.”

Most legislators were unfazed by the constitutional and practical objections to the bill. “It is a righteous measure,” declared Rep. James Robert Mann (R–Ill.). He thought the law, aimed at a drug favored by foreigners whom Congress had already deemed unfit for citizenship, was plainly “in the interest of humanity” and “one great step forward again in the civilization of the world.”

The post Anti-Chinese Xenophobia Fueled America’s First Drug War appeared first on Reason.com.