On Thursday, the Supreme Court decided that while you’re free to sell a T-shirt taking shots at a former president’s anatomy, you don’t have the right to trademark it, at least while he’s alive.

In the run-up to the 2016 presidential election, Sen. Marco Rubio (R–Fla.) accused Donald Trump of having small hands for his height, adding, “You know what they say about guys with small hands.” Days later, in a debate among the Republican candidates, Trump responded: “He referred to my hands—’if they’re small, something else must be small’—I guarantee you, there’s no problem.”

One could be forgiven for assuming this was a one-off that could not possibly one day tie up the business of the nation’s highest court. Unfortunately, that is not our reality.

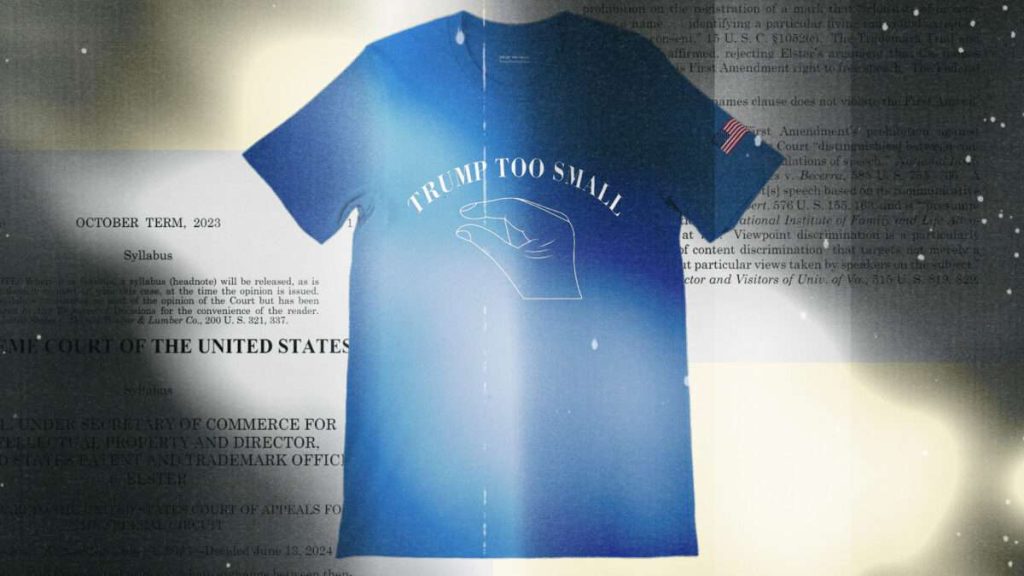

In January 2018, California attorney Steve Elster began selling T-shirts with the phrase Trump Too Small printed above an image of a hand with a thumb and forefinger pinched close together.

(Wikimedia Commons)

Elster also filed paperwork with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) for the exclusive rights to the phrase for use on shirts.

The following month, the USPTO rejected Elster’s application as a violation of Section 2(c) of the Lanham Act, which prohibits any trademark that uses “a name, portrait, or signature identifying a particular living individual.” The office found that the phrase Trump Too Small “consists of or comprises a name, portrait, or signature identifying a particular living individual” without that person’s “written consent to register the mark.” (The same law also forbids the unauthorized use of “the name, signature, or portrait of a deceased President of the United States during the life of his widow,” potentially blocking Elster’s efforts for decades.)

In an appeal, Elster claimed the logo was “core political speech about a public figure” that the average person would not likely think was “sponsored by, endorsed by, or affiliated with Donald Trump.” The office again disagreed, finding that “neither the statute nor the case law carves out a ‘First Amendment’ or a ‘political commentary’ exception to the right of privacy and publicity.”

Elster appealed the decision to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit, which decided in his favor in February 2022.

“The government does not have a privacy or publicity interest in restricting speech critical of government officials or public figures in the trademark context,” wrote Judge Timothy Dyk for the three-judge panel, “speech that is otherwise at the heart of the First Amendment.”

“As applied in this case,” Dyk concluded, the law “involves content-based discrimination that is not justified by either a compelling or substantial government interest.”

The USPTO appealed the decision to the Supreme Court, which heard the case in November. In its application, the government asked the Court to determine once and for all whether the Lanham Act’s “living individual” provision was “a condition on a government benefit or a simple restriction on speech.”

“No one doubts that political speech is ‘at the heart’ of what the First Amendment protects,” the filing stated. But the law at issue “is not a restriction on speech; it is a viewpoint-neutral condition on a government benefit”—that benefit being the singular right to sell and profit from a brand or logo.

In a joint amicus brief in favor of Elster, the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE) and the Manhattan Institute alleged that the law in question constituted “viewpoint discrimination”: Since other parts of the law already allow the government to deny false or deceptive applications, they claim, Section 2(c) merely “equip[s] named persons with the unilateral power to veto the registration of trademarks that they dislike.”

But neither the liberal nor the conservative justices found Elster’s case convincing. “He can sell as many shirts with this saying” as he wants, Justice Sonia Sotomayor noted at oral arguments, “and the government’s not telling him he can’t use the phrase.” Justice Neil Gorsuch, meanwhile, noted the “long historical tradition” of “content-based restrictions,” like the exception for living people.

In Thursday’s decision, the justices reversed the Federal Circuit’s decision and ruled in favor of the USPTO.

Justice Clarence Thomas, who delivered the majority opinion, agreed that the Lanham Act’s “names clause” was content-based but held that it is viewpoint-neutral, noting in a footnote that “the PTO has refused registration of trademarks such as ‘Welcome President Biden,’ ‘I Stump for Trump,’ and ‘Obama Pajama’—all because they contained another’s name without his consent, not because of the viewpoint conveyed.”

“The Lanham Act’s names clause has deep roots in our legal tradition,” Thomas wrote, echoing Gorsuch at oral arguments. “This history and tradition is sufficient to conclude that the names clause—a content-based, but viewpoint-neutral, trademark restriction—is compatible with the First Amendment. We need look no further in this case.”

“Our decision today is narrow,” Thomas concluded. “We do not set forth a comprehensive framework for judging whether all content-based but viewpoint-neutral trademark restrictions are constitutional. Nor do we suggest that an equivalent history and tradition is required to uphold every content-based trademark restriction.”

Instead, the Court decided simply that while Elster was free to sell T-shirts with cheeky slogans that mention Trump, he could not force the government to give him the exclusive rights to sell that shirt.

The post Supreme Court: You Can’t Trademark Your ‘Trump Too Small’ T-Shirts appeared first on Reason.com.