From Judge Loren L. AliKhan’s decision yesterday in Passantino v. Weissmann (D.D.C.):

The following factual allegations drawn from Mr. Passantino’s complaint, are accepted as true for the purpose of evaluating the motion before the court. Mr. Passantino has been a lawyer for more than thirty years. In 2017 and 2018, he served as a senior lawyer in the Trump administration. Since then, he has been in private practice.

Following the attack on the U.S. Capitol on January 6, 2021, the House of Representatives established a Select Committee to investigate what had happened. As part of its investigation, the Select Committee interviewed numerous witnesses, including Cassidy Hutchinson, a former special assistant to President Trump who had been serving under the direction of White House Chief of Staff Mark Meadows on January 6, 2021.

Mr. Passantino represented Ms. Hutchinson at her first three closed-door Select Committee depositions on February 23, March 7, and May 17, 2022. While the complaint does not specify exactly when this occurred, Ms. Hutchinson sent text messages to a friend expressing that she “d[idn]’t want to comply” with the Committee’s requests. In the same conversation, however, she noted that “Stefan [Passantino] want[ed] [her] to comply.”

Following the second deposition, Ms. Hutchinson felt that she had “withheld things” from the Select Committee and wanted to “go in and … elaborate … and kind of expand” on some topics. Unbeknownst to Mr. Passantino, Ms. Hutchinson asked a friend to “back channel to the committee and say that there [were] a few things that [she] want[ed] to talk about.” While Ms. Hutchinson deliberately kept this from Mr. Passantino, she explained at a future deposition that, at that time, she “wasn’t at a place where [she] wanted to terminate [her] attorney-client relationship with [Mr. Passantino].”

In early June 2022, after the third deposition, Ms. Hutchinson fired Mr. Passantino and retained Bill Jordan and Jody Hunt as her new counsel. She subsequently gave a fourth, televised deposition on June 28, which received substantial media coverage.

After her fourth deposition, Ms. Hutchinson sent a letter to the Select Committee stating that she intended to “waive [her] attorney-client privilege [with Mr. Passantino] in order to share information with the Committee that [was] relevant to [her] prior testimony.” The Select Committee accordingly scheduled her for a fifth deposition for September 14, 2022.

At her fifth deposition, Ms. Hutchinson revealed additional details about the preparation she and Mr. Passantino had done ahead of her first Select Committee deposition. Specifically, the two had met “for a couple hours” on February 16, 2022 to discuss her upcoming testimony. When Ms. Hutchinson suggested printing out a calendar so that she could “get[] the dates right” with respect to timelines of events, Mr. Passantino said “No, no, no.” He told her that the plan was “to downplay [her] role” and that “the less [she] remember[ed], the better.” Id. 30:19-31:2. When Ms. Hutchinson brought up an incident that occurred inside the Presidential limousine on January 6 (which she had been told about by a colleague), Mr. Passantino said “No, no, no, no, no. We don’t want to go there. We don’t want to talk about that.”

Mr. Passantino then told Ms. Hutchinson: “If you don’t 100 percent recall something, even if you don’t recall a date or somebody who may or may not have been in the room, [‘I don’t recall’ is] an entirely fine answer, and we want you to use that response as much as you deem necessary.” Id. 36:7-10. Ms. Hutchinson then asked, “if I do recall something but not every little detail, … can I still say I don’t recall?” to which Mr. Passantino replied, “Yes.” The morning of the first deposition, Mr. Passantino reminded Ms. Hutchinson to “[j]ust downplay [her] position,” telling her that her “go-to [response was] ‘I don’t recall.'”

At her fifth deposition, Ms. Hutchinson discussed a line of questioning from her first deposition about the January 6 incident in the Presidential limousine. She explained that, during a break after facing repeated questions on the topic, she had told Mr. Passantino in private, “I’m f*****. I just lied.” Mr. Passantino responded, “You didn’t lie…. They don’t know what you know, Cassidy. They don’t know that you can recall some of these things. So you [sic] saying ‘I don’t recall’ is an entirely acceptable response to this.” He concluded, “You’re doing exactly what you should be doing.” Ms. Hutchinson explained that, in the moment, she “[felt] like [she] couldn’t be forthcoming when [she] wanted to be.”

Ms. Hutchinson did, however, state at her fifth deposition: “I want to make this clear to [the Select Committee]: Stefan [Passantino] never told me to lie.” She recalled him saying to her: “I don’t want you to perjure yourself, but ‘I don’t recall’ isn’t perjury. They don’t know what you can and can’t recall.” She then reiterated to the Select Committee, “[H]e didn’t tell me to lie. He told me not to lie.”

At the Committee’s final public session on December 19, 2022, a Congressmember announced that they had “obtained evidence” that “one lawyer told a witness the witness could in certain circumstances tell the Committee that she didn’t recall facts when she actually did recall them.”

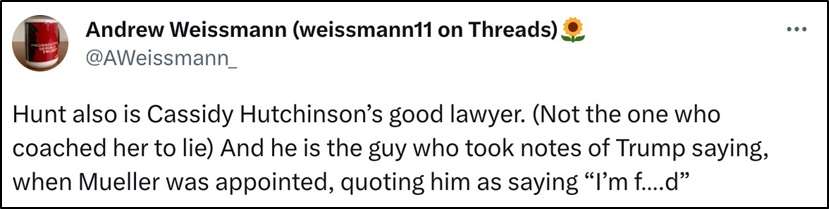

After the Committee released the transcripts from the Ms. Hutchinson’s closed-door depositions, multiple news outlets claimed that the “lawyer” referred to by the Select Committee member was Mr. Passantino. On September 15, 2023, Mr. Weissmann—a former prosecutor who now serves as a “political pundit” for MSNBC—posted the following on X (formerly known as Twitter):

Mr. Weissmann made the post in response to an alert that Mr. Hunt had been subpoenaed in an unrelated case. Mr. Weissmann had approximately 320,000 followers on X at the time.

Passantino sued for defamation (and a related tort), and the court allowed the defamation claim to go forward:

Mr. Passantino alleges that Mr. Weissmann’s post “deeply damaged [his] 30-year reputation and caused him to lose significant business and income.” Prior to the allegations surrounding his representation of Ms. Hutchinson, Mr. Passantino had “never been accused by a client, or anyone else, of unethical or illegal behavior.” …

The parties agree that this motion boils down to a core question: was Mr. Weissmann’s social media post that “[Mr. Passantino] coached [a witness] to lie” a verifiably false fact, or a subjective opinion? This is not an easy inquiry, and the answer in such cases is rarely clear cut.

{For the purposes of this motion, the parties do not dispute other possible defenses to a claim for defamation, such as whether the content of Mr. Weissmann’s post was substantially true. After this court’s resolution of the motion to dismiss, Mr. Weissmann is free to raise any such defenses not barred by the Federal Rules. See Long v. Howard Univ. (D.C. Cir. 2008) (“[A] defense can be raised [as late as] at trial so long as it was properly asserted in the answer and not thereafter affirmatively waived.”). The court is thus only deciding whether Mr. Weissmann’s statement is nonactionable as a subjective opinion.}

The first Ollman v. Evans (D.C. Cir. 1984) (en banc) factor requires the court to determine whether the challenged statement “has a precise meaning and thus is likely to give rise to clear factual implications.” The touchstone of this inquiry is whether “the average reader [could] fairly infer any specific factual content from [the statement].” As the Ollman court noted, “[a] classic example of a statement with a well-defined meaning is an accusation of a crime.” The allegedly defamatory portion of the post can be distilled into: “[Mr. Passantino] coached [Ms. Hutchinson] to lie.” …The definition of the verb “coach” is “to instruct, direct, or prompt.” While Mr. Weissmann argues that “coached” is “indefinite,” “ambiguous,” and “can ‘mean different things to different people at different times and in different situations,'” the court concludes that the word conveys a sufficiently precise meaning in the challenged social media post.

Readers of a statement do not isolate and parse individual words into all of their possible connotations. Mr. Weissmann wrote that Mr. Passantino “coached [a witness] to lie.” In that string of text, read as a whole, the clear factual implication is that Mr. Passantino “instruct[ed], direct[ed], or prompt[ed]” Ms. Hutchinson “to lie” to the Select Committee. While it is true that general statements that someone is “spreading lies” or “is a liar” are not categorically actionable in defamation, Mr. Weissmann’s post very directly claimed that Mr. Passantino had committed a specific act—encouraging or preparing a specific witness to make false statements. A reasonable reader is likely to take away a precise message from that representation.

[The second factor is the d]egree to which the statements are verifiable ….. Verifiability hinges on a deceptively difficult question: “is the statement objectively capable of proof or disproof?” In some ways, this second factor overlaps with the first because the common usage of the statement’s words will determine whether the statement—as a whole—can be proven true or false.

Mr. Weissmann advances two arguments for why the statement is not verifiable. First, he reasserts his claim that “coached” is too ambiguous of a term, and that “a statement with a number of possible meanings is by its nature unverifiable.” However, as discussed above, the phrase “coached her to lie” is sufficiently precise to “give rise to clear factual implications.” Mr. Weissmann’s ambiguity argument is therefore not persuasive.

Second, Mr. Weissmann asserts that there is no objective standard for assessing when someone has coached another to lie—at least in the absence of an explicit instruction to do so. For support, he cites various cases for the proposition that evaluating a lawyer’s performance is “not susceptible of being proved true or false.” Those cases are not particularly useful, however, because they primarily discuss the quality of an attorney’s representation, not whether the attorney committed or engaged in a particular act. There is a difference between calling an attorney’s representation “good” or “bad,” on one hand, and saying that an attorney “lied” or “told the truth,” on the other. The former is a subjective spectrum indicative of an opinion; the latter is a yes-or-no binary indicative of a fact….

As for the cases that do concern the act of witness preparation (rather than the quality of an attorney’s representation generally), an “objective standard” is only lacking if the court assumes that the term “coach” is ambiguous. If one reasonably reads “coach” to mean “instruct, direct, or prompt” in the context of Mr. Weissmann’s full social media post, then the statement is verifiable. Mr. Passantino either “coached”—that is, he “instruct[ed], direct[ed], or prompt[ed]”—Ms. Hutchinson to lie, or he didn’t. The second Ollman factor thus favors Mr. Passantino.

[The third factor is the c]ontext in which the statement occurs…. This inquiry focuses on the immediate context surrounding the challenged statement. For example, a sentence asserting a seemingly factual claim takes on an entirely different meaning if situated in a satirical newspaper column….

Here, Mr. Weissmann’s post contained only three sentences. It began by stating that “[Mr.] Hunt is Cassidy Hutchinson’s good lawyer.” Both parties agree that this is “obviously” an opinion. Then, in a parenthetical, it reads: “(Not the one who coached her to lie).” Finally, it concludes, “And [Mr. Hunt] is the guy who took notes of Trump saying, when Mueller was appointed, quoting him as saying ‘I’m f….d.'” Mr. Passantino argues that the final sentence is clearly a factual assertion, and Mr. Weissmann does not contest that characterization.

Nothing about the surrounding context suggests that the reference to Mr. Passantino’s “coach[ing]” Ms. Hutchinson “to lie” is facetious or sarcastic. It presents neutrally, nestled between a statement of opinion and a statement of fact. Mr. Weissmann contends that because the challenged statement follows a statement of opinion, it must also be an opinion, especially because it comes in the form of a parenthetical. Mr. Passantino takes the opposite view, arguing that the challenged statement must be a statement of fact because it is followed by a statement of fact. Given how short the full statement is, the court cannot divine much from the contested language’s location to determine whether it is presented as a subjective thought or a verifiable fact….

The fourth and final Ollman factor evaluates the broader social context beyond the statement and its immediate surroundings…. Starting with X, the statement’s backdrop, Mr. Weissmann asserts that it is generally considered an “informal” and “freewheeling” internet forum. [S]ome courts have held that “the fact that Defendant’s allegedly defamatory statement … appeared on Twitter conveys a strong signal to a reasonable reader that [it] was Defendant’s opinion.”

While Mr. Weissmann is correct that X is seen by many as a free market for the exchange of subjective ideas, its use is not always one-sided. Journalists and reporters use X to post news alerts and factual content…. [I]nferring that Mr. Weissmann’s statement was an opinion based solely on his use of the X platform risks overlooking “society’s expectations of journalistic conduct on [X].” That is especially so when Mr. Weismann is a public figure connected to a news organization and not a private user.

This leads to Mr. Weissmann’s status as a “political pundit.” … Mr. Passantino asserts that Mr. Weissmann’s career as a former prosecutor, his twenty-plus years of experience in the Department of Justice, and his record as an accomplished author of a book about federal prosecutions make his audience more likely to view his statements as facts. And while Mr. Weissmann currently serves as a political commentator on MSNBC, Mr. Passantino argues that that should not shield his comments from liability.

Mr. Passantino is correct that “there is no blanket immunity for statements that are ‘political’ in nature … [because] the fact that statements were made in a political context does not indiscriminately immunize every statement contained therein.” Individuals who immerse themselves in political commentary are still capable of defaming others with verifiably false assertions. And, presumably, Mr. Weissmann does not limit his social media activity strictly to offering opinions. After all, at least one-third of the social media post in question was an expression of objective fact. Clearly, then, Mr. Weissmann’s audience of followers can expect him to present some statements of fact.

At the same time, Mr. Weissmann is correct that reasonable readers know to expect subjective analysis from commentators. As a political pundit (rather than, say, a news anchor), his statements possess a general air of opinion rather than fact. “Reasonable consumers of political news and commentary understand that spokespeople are frequently (and often accurately) accused of putting a spin or gloss on the facts or taking an unnecessarily hostile stance toward the media or others.” And numerous courts have held that the average reader, viewer, or listener tempers his or her expectations of hearing factual reporting in the world of punditry….

On balance, the fourth factor weighs in Mr. Weissmann’s favor. But even so, the court concludes that the overall analysis of the Ollman factors suggests that his statement was not a subjective opinion.

Again, keep in mind that this merely resolves that the statement is a factual assertion; to prevail, plaintiff must still show that it’s false and that defendant said it with the requisite mental state.

The post MSNBC Pundit’s Tweet Accusing Lawyer of “Coach[ing a Witness] to Lie” Is a Potentially Defamatory Factual Assertion, Not an Opinion appeared first on Reason.com.