Syrian President Ahmad al-Sharaa and Gen. Mazloum Abdi make an odd couple. Abdi is a Kurdish rebel leader whose secular army boasts all-women units and fights alongside the U.S. military. Sharaa, formerly known as Abu Mohammad al-Golani, is a former franchisee of Al Qaeda who runs the new Islamist government in Damascus.

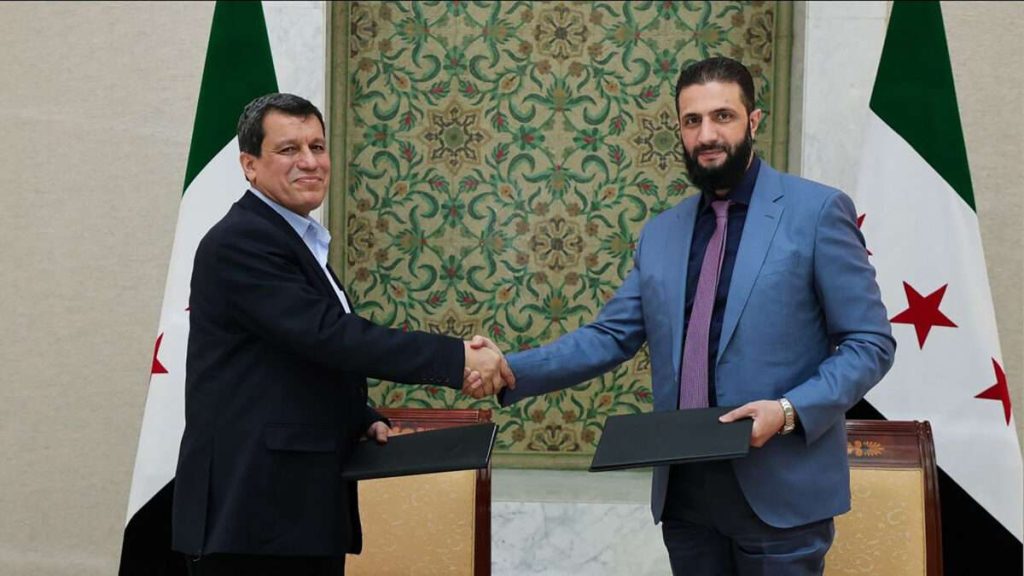

Yet the two men, both of whom traded in their military fatigues for ill-fitting suits, were shaking hands and grinning for the camera on Monday. They had an agreement—at least in principle—for Abdi’s Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) to merge into the government in exchange for Sharaa recognizing Kurds’ hard-won rights. The exact details would be hammered out by the end of 2025 by a newly formed committee.

The deal was an attempt by war-weary Syrian factions to stop their country’s violence once and for all. It was also a triumph of behind-the-scenes U.S. diplomacy. The U.S. government has been playing “a very crucial role” in the negotiations, sources told Reuters. And that role, including American mediators in the room, has been an open secret. Abdi was photographed flying to Damascus on a U.S. military helicopter, flanked by U.S. troops. Gen. Michael Kurilla, head of U.S. forces in the Middle East, had publicly visited Syria and met with SDF leaders the weekend before the meeting.

President Donald Trump has long wanted to pull U.S. troops out of Syria. But his previous attempt to do so, in October 2019, was a violent catastrophe. Turkey took Trump’s withdrawal announcement as a green light to attack the SDF, and hawks in the administration played what they openly called “shell games” to keep U.S. forces in the country anyway.

A deal between the SDF and the central government might be the best opportunity for a graceful U.S. exit. In fact, Syria TV claims that the deal between Abdi and Sharaa was inked as a direct response to Trump telling his generals to pull U.S. troops out of Syria.

“The United States welcomes the recently announced agreement between the Syrian interim authorities and the Syrian Democratic Forces to integrate the northeast into a unified Syria,” U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio said in a statement on Tuesday. “The United States reaffirms its support for a political transition that demonstrates credible, non-sectarian governance as the best path to avoid further conflict. We will continue to watch the decisions made by the interim authorities, noting with concern the recent deadly violence against minorities.”

The elephant in the room is the massacres against Alawite Muslims last weekend. (The atrocities were falsely reported as attacks on Christians by some foreign media.) The overthrown former ruler, Bashar al-Assad, belonged to the Alawite community, which makes up around 10 percent of the Syrian population. When insurgents in Alawite towns rose up against the new government, Sharaa declared war on the alleged “Assad remnants.” Sharaa’s supporters went on to murder between 420 and 1,383 civilians.

Counterintuitively, these atrocities may have presented a strong reason for both sides to avoid fighting each other. Sharaa has blamed the war crimes on rogue elements. As veteran war reporter Aris Roussinos has argued, that excuse actually bodes badly for his “prospects of stable domestic rule or widespread international legitimacy” because “Sharaa’s grip on power is surely weaker than many external observers assumed.” On the other hand, the massacres demonstrated that a conflict with Damascus could have terrible consequences for the Kurdish community as a whole.

Neither side can really afford to reignite the civil war, especially because both are also dealing with foreign threats. The Syrian government is facing a low-grade border war with Israel in the south, while the SDF is facing a low-grade border war with Turkey in the north, both of which threaten to become wider invasions.

It’s probably no coincidence that the SDF’s negotiations with Damascus lined up with a new Turkish-Kurdish peace process. Abdullah Öcalan, leader of the underground Kurdistan Workers Party and the Turkish government’s public enemy number one, issued a statement from his jail cell last month calling for Kurdish rebels to lay down their arms. After Sharaa and Abdi signed their deal, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan praised the triumph for “all our Syrian brothers and sisters.”

Thus far, Sharaa’s supporters have been celebrating the deal as a great victory. “Thank God, Syria is now united after being divided into parts. We thank the leadership and the mujahideen brothers,” a demonstrator at a pro-government rally told Agence France Presse.

So has the SDF’s leadership. Prominent Syrian Kurdish politician Salih Muslim declared in an interview with Kurdish media on Tuesday that “the Rojava Revolution has been consolidated. From now on, we are partners in everything related to this state—its administration, constitution, daily life, economy, everything.”

The devil, of course, is in the details. The agreement calls for all Syrian oilfields to be returned to the central government, but the SDF has not been keen on giving up its control over a key resource. The deal also promises to allow displaced Syrians to return home, a reference to Syrian Kurds ethnically cleansed by Turkey and Turkish-backed warlords. However, Sharaa’s government includes many of those warlords, including the infamous Abu Amsha, who was allegedly involved in massacring Alawites last weekend.

Syrian journalist Hussam Hammoud argued that the deal is actually a “dangerous development” for Syria because the “armed blocs remain intact, meaning the conditions for chaos and armed conflict still strongly persist.”

On the other hand, some SDF supporters worry that the deal doesn’t go far enough to preserve the independence of their militias. A big open question is what will happen to the famous Kurdish female guerrillas when the SDF merges into the Syrian army. Rihan Loqo, spokeswoman for the Kurdish feminist organization Kongra Star, argued that “women’s rights should have been guaranteed” in the deal because of the ongoing “attack against the identity of women, their achievements, their existence and culture” in Syria.

The Syriac Union Party, meanwhile, stated that Abdi and Sharaa’s deal “is incomplete and does not reflect the aspirations and rights of the Syriac-Assyrian component,” referring to the Aramaic-speaking Christian community. The agreement speaks about guaranteeing the rights of Kurds—most of whom are Muslim—but doesn’t mention the non-Muslim, non-Kurdish minorities that fought under the SDF flag.

The first conflict between Damascus and the SDF began on Thursday, when Sharaa signed a “temporary” constitution that is supposed to govern the country until elections are held. (Although it mentions freedom of religion and separation of powers in theory, the constitution also calls Islam “the main source of legislation” and replaces parliament with a council handpicked by Sharaa.) The SDF’s political branch stated that it “completely rejected” Sharaa’s declaration, which “reproduced authoritarianism in a new form,” and argued that the Syrian constitution “must be the result of genuine national consensus, not a project imposed by one party.”

Still, the great achievement of the Sharaa-Abdi deal is putting these issues back into the hands of Syrians themselves. Although the U.S. military hasn’t left yet, and doesn’t seem to be doing so immediately, Trump made his general policy on Syrian politics clear last year: “THE UNITED STATES SHOULD HAVE NOTHING TO DO WITH IT. THIS IS NOT OUR FIGHT. LET IT PLAY OUT. DO NOT GET INVOLVED!”

The post Has Trump Cut a Deal To Get U.S. Troops Out of Syria? appeared first on Reason.com.