Wander through the streets of Seville or Porto, and you’ll find yourself immersed in a world of color and intricate patterns. Elaborately painted tiles, called azulejos, adorn churches, palaces, train stations, and sidewalks.

These tiles are more than mere decoration—they’re storytellers, chronicling centuries of cultural exchange, artistic innovation, and political power in Iberia. Some whisper tales of ancient civilizations; others speak of grand adventures. Above all, azulejos reveal the story of a region that has long been at the forefront of globalization.

The story of azulejos begins with the Muslim conquest of the peninsula. In the year 711, the Moors swept into the Iberian Peninsula from North Africa, bringing advanced ceramic techniques from the Muslim world. Their hallmark was the art of zellij, an Islamic mosaic style made from hand-chiseled tiles arranged in intricate geometric patterns. Symmetry and abstraction dominated these designs, with motifs inspired by plants, calligraphy, and geometry—a reflection of the prohibition against depicting living creatures in Islamic art. The result was stunning: Walls and courtyards shimmered with patterns inspired by nature and mathematics.

For nearly 800 years, Moorish rule brought cultural and technological advancements to cities such as Córdoba and Granada. They became hubs of tile-making innovation, with artisans developing precise interlocking designs, vibrant glazing techniques, and kilns capable of producing durable ceramics. The Alhambra palace in Granada stands as a monument to this era. Its designs were a political statement—symbols of power and authority that reflected the wealth, sophistication, and influence of the rulers who commissioned them. It was during this time that the term azulejo (derived from the Arabic al-azulayj meaning “small polished stone”) came into use.

By the late 1400s, the tides had turned. The Catholic monarchs reclaimed the peninsula, driving out the Moors and reasserting Christian dominance. But the allure of Moorish architecture was too strong to resist. Instead of erasing the Islamic aesthetic, the new rulers embraced it, commissioning Muslim artisans to craft tiles for their churches, palaces, civic buildings, and homes. This fusion of cultures gave rise to the Mudéjar style, which merged intricate Islamic techniques with Christian themes.

Seville’s Real Alcázar is one of the finest examples of this phenomenon. Originally a Moorish fort, it was transformed into a palace for Christian rulers after the Reconquista. Inside, the tilework tells the story of adaptation, harmoniously blending Islamic techniques with Christian iconography.

In the 16th century, with Christopher Columbus’ voyages opening the Americas to Europe, Seville became a gateway for transatlantic trade. Among other new influences to the Iberian Peninsula were Italian merchants, who brought with them the technique of maiolica—a method of painting on tin-glazed pottery that allowed for more vibrant, detailed designs. This method revolutionized azulejo production, allowing artisans to depict more complex narratives on the tiles.

The tiles didn’t just remain in Europe—they traveled with explorers, adorning homes and official buildings in colonies from Cuba to Peru. In these distant lands, azulejos were reshaped by local tastes, carrying the marks of globalization long before the term existed.

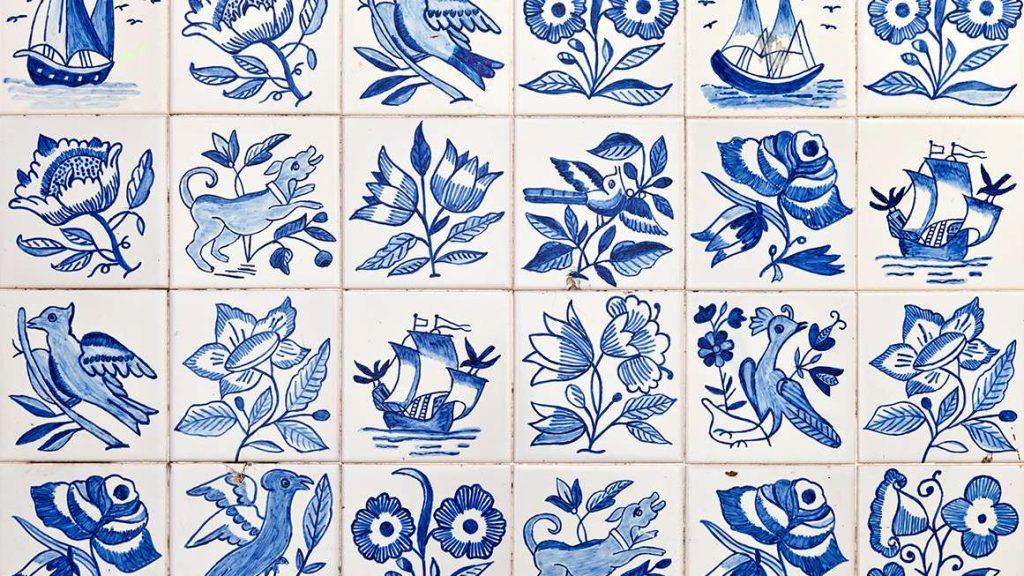

While azulejos gained prominence in Spain, they became a defining feature of Portuguese identity. After visiting Seville in 1498, King Manuel I fell in love with the geometric-patterned tiles. The king brought tiles back to decorate his palace in Sintra, which still houses one of Europe’s largest collections of Mudéjar tiles. The Portuguese soon innovated beyond Spanish influences, creating grand murals that celebrated the country’s maritime power and its pivotal role in global trade. By the 17th century, Portugal’s maritime trade with China and the Dutch introduced new artistic inspirations, creating the iconic blue-and-white azulejos.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, advancements in industrial technology changed everything. Factories in Lisbon and Aveiro began mass-producing azulejos, using molds and machine-printed patterns to reduce costs. What had once been a luxury reserved for churches and palaces became a common feature in middle-class homes and train stations. Tiles became an everyday staple but they continued to carry their cultural heritage, preserving centuries of artistic tradition in their designs.

Azulejosare more than art—they are history embedded in ceramics. They remind us that globalization isn’t a modern phenomenon; it’s been shaping art, politics, and culture for centuries. Whether you’re tracing the geometric patterns of the Moorish zellij in Granada, strolling through the tiled courtyards of Seville, or marveling at Lisbon’s murals in train stations, each azulejo is a testament to the enduring connections between past and present, local and global.

The post These Ceramic Tiles in Spain and Portugal Tell the Story of Globalization appeared first on Reason.com.