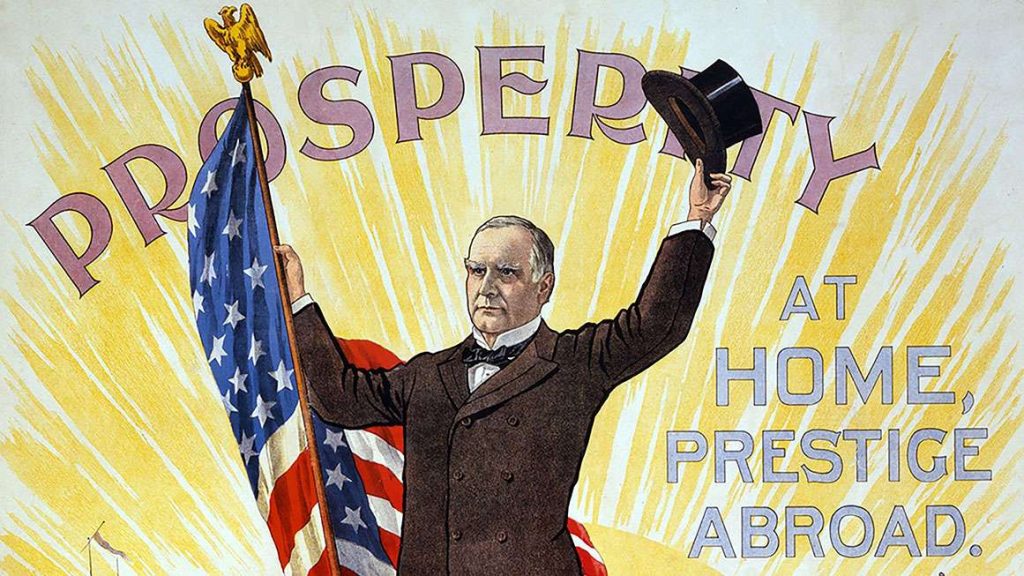

On his first day back in office, Donald Trump praised his new presidential role model, William McKinley, for having “made our country very rich through tariffs.” He then signed an executive order re-renaming the highest peak in North America “Mount McKinley.”

The 25th president, Trump wrote in the order, “heroically led our Nation to victory in the Spanish-American War. Under his leadership, the United States enjoyed rapid economic growth and prosperity, including an expansion of territorial gains for the Nation. [He] championed tariffs to protect U.S. manufacturing, boost domestic production, and drive U.S. industrialization and global reach to new heights.”

Twelve days later, Trump announced (then waffled on) blanket 25 percent tariffs on goods coming from Canada and Mexico. “Anybody that’s against Tariffs,” he contended on social media, “is only against them because these people or entities are controlled by China, or other foreign or domestic companies. Anybody that loves and believes in the United States of America is in favor of Tariffs.”

Who knew that McKinley was controlled by China?

It is true that the self-styled “tariff man”—his political opponents preferred the more derisive “Napoleon of protection”—was the biggest public face of mercantilism during America’s high-tariff era of 1870–1912. As a congressman, he wrote what came to be known as the “McKinley tariff” of 1890, and as president he signed another increase in 1897.

But a funny thing happened after the U.S. came out of the Panic (and subsequent four-year depression) of 1893: Goosed by sharp increases in domestic iron and copper production, Americans had too many goods chasing too few consumers. And McKinley himself began agitating to tear down some of those trade barriers.

“What we produce beyond our domestic consumption must have a vent abroad,” he said in September 1901 at the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, New York. “The excess must be relieved through a foreign outlet, and we should sell everywhere we can, and buy wherever the buying will enlarge our sales and productions, and thereby make a greater demand for home labor. The period of exclusiveness is past,” he continued. “The expansion of our trade and commerce is the pressing problem. Commercial wars are unprofitable….If perchance some of our tariffs are no longer needed, for revenue or to encourage and protect our industries at home, why should they not be employed to extend and promote our markets abroad?”

McKinley’s presidency was ended by an assassin’s bullet the very next day.

Even before his late-life pivot to freer trade, McKinley had long been a champion of reciprocity, i.e., the bilateral, mutually beneficial reduction of targeted, asymmetrical tariffs. Or, as he put it in his first inaugural address, “the opening up of new markets for the products of our country, by granting concessions to the products of other lands that we need and cannot produce ourselves, and which do not involve any loss of labor to our own people, but tend to increase their employment.”

In his second term, Trump has demonstrated less enthusiasm for reciprocity than he has for the other two Rs of traditional protectionism, revenue and restriction. Asked last October by Joe Rogan whether he was serious about replacing the federal income tax with tariffs, Trump said, “Yeah, sure. Why not?”—and then engaged in some historical revisionism. “Our country was the richest in the [world], relatively, in the 1880s and 1890s. A president who was assassinated named McKinley—he was the tariff king. He spoke beautifully of tariffs. And then around in the early 1900s, they switched over, stupidly, to frankly an income tax. And you know why? Because countries were putting a lot of pressure on America: ‘We don’t want to pay tariffs, please don’t.’ You know they, believe me, they control our politicians.”

Trump’s account, besides skipping over McKinley’s second-term second thoughts, vastly overstates the then-negligible foreign influence on early 20th century American politicians while ignoring the primary motivation for swapping tariffs for an income tax—what could have been called a fourth R, rent seeking.

Put plainly, the tariff system and perennial adjustments thereof was a cornucopia of corruption, putting the gilded in Gilded Age. Far from being a sophisticated manipulation of import/export duties to nurture nascent industries, the tariff schedule was a Christmas tree decorated by special interests.

“The struggle for unearned advantage at the doors of the government tramples on the rights of those who patiently rely upon assurances of American equality,” Grover Cleveland wrote in his 1892 letter accepting the Democratic Party’s nomination for president. “Every governmental concession to clamorous favorites invites corruption in political affairs by encouraging the expenditure of money to debauch suffrage in support of a policy directly favorable to private and selfish gain. This in the end must strangle patriotism and weaken popular confidence in the rectitude of republican institutions.”

Cleveland, the only Democratic president from 1870 through 1912, was also the only before Trump to serve nonconsecutive terms (1885–89, 1893–97). He was anti-corruption, anti-tariff, and anti-imperialist, correctly viewing those three stances as inextricably linked. So boggy was Washington’s swamp at the time that Cleveland’s core campaign promise of freer trade became riddled with special-interest carve-outs, to the point where the president accused his own party of “perfidy” and “dishonor,” and refused to affix his signature to the 1894 tarrif-reduction law.

It was the blatantness of the palm greasing, whether import duties were going up or down, that eventually led to shifting the federal government’s main income source away from tariffs. “The sheer extravagance of the public corruption around tariff schedule revisions,” economic historian Phillip W. Magness wrote for the Cato Institute in 2023, “came to a head in the late 19th century, eventually leading reformers to call for the abandonment of a tariff-based revenue system.”

Trump has great executive latitude to increase or enact tariffs; any tax reduction (let alone abolition), on the other hand, would have to skate through the GOP’s razor-thin margin in Congress. He is almost certain to increase protectionism over a first term that saw more than 200,000 individual tariff waivers granted to special-pleading U.S. companies.

Perhaps instead he should listen more to his hero McKinley. “Isolation is no longer possible or desirable,” the Tariff Man said the day before he was shot. “We must not repose in fancied security that we can forever sell everything and buy little or nothing.”

The post Trump Is Wrong About McKinley’s Tariff Legacy appeared first on Reason.com.