As the U.S. presses its trading partners to cut ties with China, Beijing is reminding neighbors in Southeast Asia that doing Washington’s bidding will come at a cost.

On Monday, Beijing said it “resolutely opposes any party reaching a deal [with the U.S.] at the expense of China’s interest,” and threatened retaliation in the event that a country did try to sacrifice trade with China.

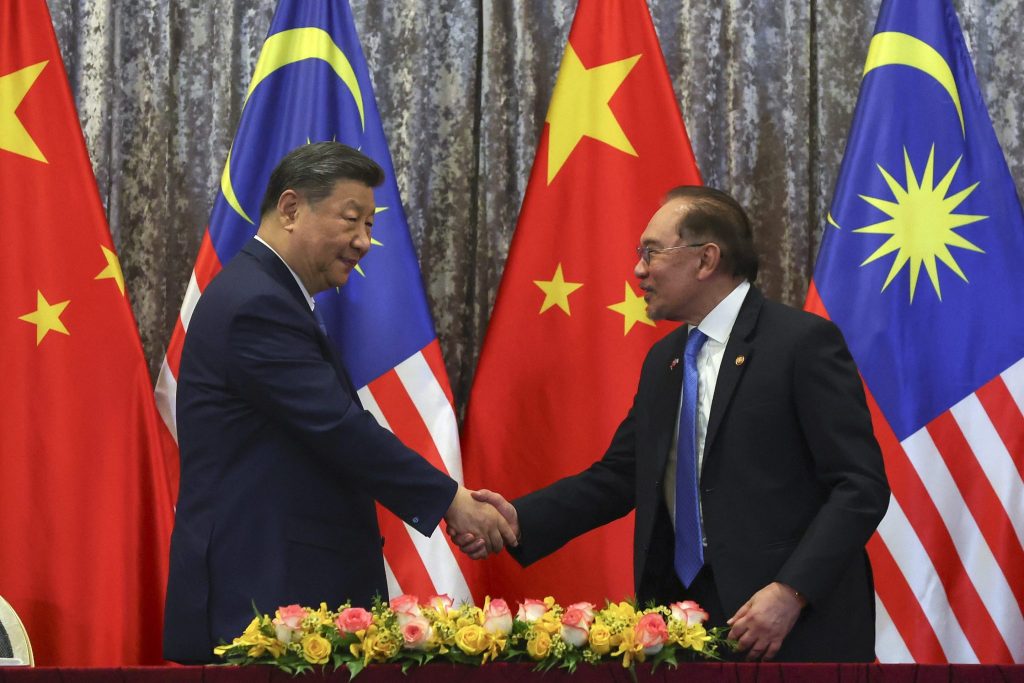

China’s warning comes after a weeklong visit by President Xi Jinping to Vietnam, Malaysia and Cambodia, against the backdrop of global trade uncertainty emanating from the White House.

Xi’s trip “was a reassurance and a warning,” says Trinh Nguyen, senior economist for emerging Asia at Natixis. She suggests the trip was a reminder to Southeast Asian economies that China wants to be seen as a responsible actor, and open to engaging with neighbors on trade.

China is trying to “remind Asia that there’s always an alternative [to the U.S.],” says Sheana Yue, a Singapore-based economist at Oxford Economics, adding that Southeast Asian economies want to be able to keep access to China’s large market.

Chinese economic heft and Trump policy uncertainty could allow Beijing to promote the “Asia moment” where the dominant global order shifts to Asia, says Alfred Wu, an associate professor at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy at the National University of Singapore.

For years, Beijing has tried to present itself as an alternative to the U.S., particularly to neighboring Southeast Asia, a large trading partner. “Over the past two years, they’re using these [ideas] to counter the dominant global order,” Wu says, noting that China has increasingly referred to these ideas since 2022.

Southeast Asia in the middle

Southeast Asian economies like Vietnam, Thailand, and Malaysia have benefited from supply chain diversification, as companies adopted a “China plus one” strategy. That helped boost their exports, particularly to the U.S.

Some of that boost has come from China. Nguyen, from Natixis, notes that Vietnam’s northern region has benefited from Chinese investment in infrastructure and manufacturing.

Yet surging exports led Trump to threaten higher tariffs on these countries, including a 46% tariff on Vietnam. The White House’s tariff calculations suggest the purpose of the “Liberation Day” taxes was to drive the U.S. trade deficit down to zero.

The U.S. has paused the implementation of these tariffs for 90 days, setting off a scramble among Southeast Asian countries to negotiate some kind of deal. Vietnam, Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, and Singapore are all engaging with the Trump administration.

The U.S. is reportedly pressuring trading partners to decouple with China, suggesting that countries control trade with the world’s second-largest economy as a condition of open, tariff-free trade with the U.S.

Vietnam is also reportedly offering to scrutinize inbound trade from China as part of a deal with the U.S.

China signed several agreements and MOUs with Southeast Asian partners during Xi’s visit. While there were few concrete details of those announcements, Yue, from Oxford Economics, thinks these agreements allow Southeast Asian economies to continue juggling relations between the world’s two largest economies.

Southeast Asian countries “still want access to the China market, and they also want the investments Chia is willing to give,” Yue explains. “But they also have to ensure they aren’t seen as too friendly to China because that’s going to complicate their negotiations with the U.S.”

Many Southeast Asian countries say they want to remain neutral between Washington and Beijing. And running afoul of China, the region’s largest trading partner, could have serious consequences.

China still supplies many of the inputs that are used in Southeast Asian manufacturing, which in turn are exported all over the world.

The country is also one of the largest sources of tourists to countries like Thailand, Malaysia, and Singapore. Beijing could potentially discourage its citizens from travelling to those countries, thus hitting their respective tourism sectors, something which has happened before.

In 2017, China barred group travel to South Korea in response to the U.S. deployment of the THAAD anti-missile system. The ban had an almost immediate effect on travel, with tourist numbers from China falling by nearly 20%. It took until 2023 for Beijing to lift the ban.

This story was originally featured on Fortune.com