Uncle Sam conducted several pointless and destructive experiments on his own people during the Cold War. The most infamous was MKUltra, the CIA’s project to develop procedures for mind control using psychedelic drugs and psychological torture. During Operation Sea-Spray, the U.S. Navy secretly sprayed San Francisco with bacteria to simulate a biological attack. San Francisco was also the site of a series of radiation experiments by the U.S. Navy.

A 2024 investigation by the San Francisco Public Press and The Guardian revealed that the city’s U.S. Naval Radiological Defense Laboratory had exposed at least 1,073 people to radiation over 24 experiments between 1946 and 1963. The tests came during a time when the effects of nuclear radiation were a pressing concern, and were conducted without ethical safeguards.

Conscripted soldiers and civilian volunteers were sent into radioactive conditions or purposely dosed with radiation without their informed consent. The lab didn’t bother following up on the long-term health effects. In fact, the government didn’t even bother holding on to its own results. The Public Press had to piece together the stories from papers in old cardboard boxes after the Navy shredded millions of pages.

The cleanup of the Radiological Defense Laboratory, which closed in 1969, has been a well-known issue in San Francisco politics. In 2013, whistleblowers brought a lawsuit against a decontamination contractor for cutting corners and faking results; in January 2025, the contractor agreed to pay a $97 million settlement. The Public Press used the Freedom of Information Act and other archives to figure out what exactly the government was doing that needed cleaning up.

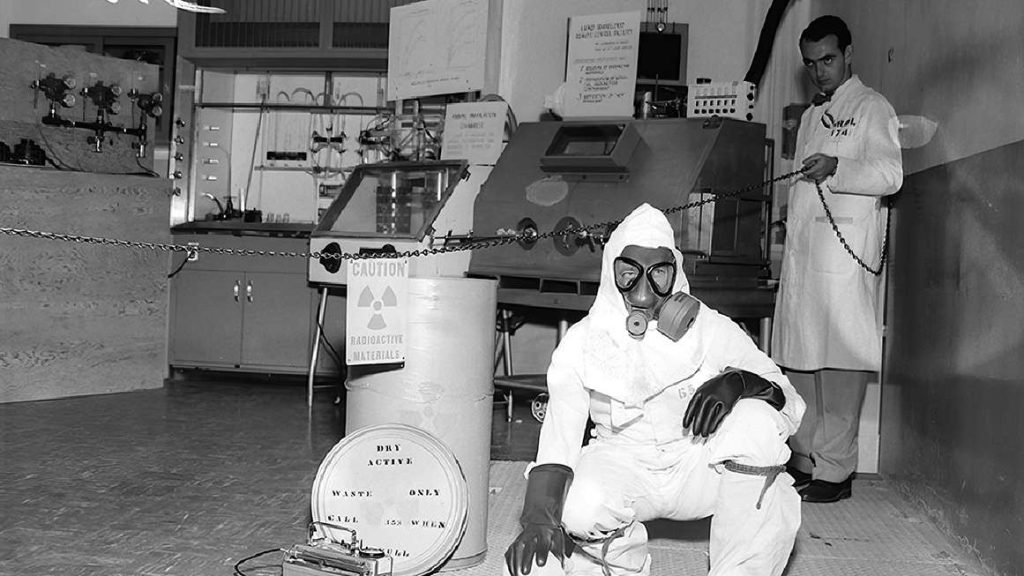

The laboratory’s work began with decontaminating ships that had been irradiated during nuclear tests. Scientists later developed “synthetic fallout”—dirt laced with radioactive isotopes to simulate the waste created by a nuclear war. They had test subjects practice cleaning it up, rub it on their skin, or crawl around in it. At least 35 men were injected with radioactive materials to see how they traveled through the body. Even the consenting volunteers were often given doses higher than the limits the scientists themselves had set.

Cpl. Eldridge Jones was an example of how much radiation the government might expose a single person to. He was deployed with the U.S. Army’s 50th Chemical Platoon to five different nuclear tests in 1955. Later, the Radiological Defense Laboratory had him shoveling synthetic fallout to test decontamination techniques. “In the military, they tell you what to do, and you do it,” he told the Public Press. Jones, who is still alive as of press time, says many of his platoonmates died young and blames his own health problems, such as impaired blood flow and partial blindness, on the experiments.

The U.S. government’s negligent curiosity about radiation poisoning was an overcorrection to its previous negligent ignorance about the subject. Robert Oppenheimer and Gen. Leslie Groves, who ran the World War II–era nuclear weapons program, were completely unconcerened by the effects of nuclear fallout, according to research by historian Sean Malloy.

U.S. military planners were told that they could send troops “immediately” into cities struck by atomic bombs, and Groves dismissed reports of radiation poisoning in Hiroshima and Nagasaki as Japanese propaganda. By November 1945, when the number of radiation victims was impossible to deny, Groves testified to the Senate that radiation poisoning is “a very pleasant way to die.”

Radiation does terrifying and gruesome things to the human body. And those things were militarily relevant because the U.S. and Soviet Union were preparing to fight each other in the postnuclear ruins of Europe. Both countries combined nuclear testing with army exercises, having soldiers march toward radioactive mushroom clouds. Scientists whose work was related to this kind of warfare could get a virtually unlimited supply of money and test subjects (willing or not) from the government.

Radiological Defense Laboratory Director Paul Tompkins was clear that the work had value only to the military, not to the public at large. “Research from the scientific viewpoint doesn’t have much to offer at the present time, but ‘basic’ data from the viewpoint of the military problems is so sparse that it is somewhat dangerous,” he wrote in a 1953 memo obtained by the Public Press.

One of his colleagues, Stanton Cohn, was more blunt in a 1982 interview with a government historian: “We could buy any piece of machinery or equipment, and you never had to justify it….We did a lot of field studies and got nothing to show for it.”

The post When the U.S. Military Gave People Radiation Poisoning appeared first on Reason.com.