Colon cancer is the third most commonly diagnosed cancer worldwide and the second leading cause of cancer-related death.1 In the United States, it is increasingly affecting adults under 50. Each year, more than 150,000 people are diagnosed, and over 50,000 lose their lives to the disease.2

Although improvements in screening and treatment have helped detect cancer earlier and extend survival, the risk of recurrence remains a serious concern, even after surgery and chemotherapy. In response, researchers have turned their attention to supportive care strategies that promote long-term health and reduce the chance of relapse.

Among these, physical activity has consistently drawn interest for its protective benefits. A new study published in the New England Journal of Medicine adds to this growing body of evidence, suggesting that structured exercise offers therapeutic value when integrated into cancer care.3

Structured Exercise Improves Survival After Colon Cancer Treatment

The featured study, called the CHALLENGE trial, is a major international study that aims to determine whether structured exercise could help people who had been treated for stage 2 or 3 colon cancer stay cancer-free longer and live longer overall. Nearly 900 participants took part, all of whom had completed surgery and chemotherapy.4

• Participants were randomized into two groups — One group received general health education materials encouraging physical activity. The other group received those same materials along with a personalized, three-year exercise program. This program included regular coaching sessions that helped participants gradually increase their activity, focusing on moderate, consistent movement like brisk walking or light jogging.

• The exercise targets were designed to be achievable — The weekly goal was 20 metabolic equivalent tasks (MET)-hours per week, a standard measure of energy expenditure. This is equivalent to five one-hour brisk walks or about two hours of jogging. The program emphasized gradual increases, long-term adherence, and a sustainable, individualized approach rather than intensity or uniform prescriptions.

• Activity levels rose significantly in the exercise group — At baseline, both groups averaged around 10 MET-hours per week. Over time, the exercise group averaged 20 MET-hours, while the education group increased only slightly to about 15.

The exercise group also showed improvements in cardiorespiratory fitness and physical function. Musculoskeletal complaints, such as soreness or mild strains, were reported in 18.5% of the exercise group, compared to 11.5% in the education group, and were generally manageable.

• Exercise improved disease-free survival — After nearly eight years of follow-up, those in the exercise group had a significantly better chance of staying cancer-free. After a follow-up of 7.9 years, five-year disease-free survival was 80.3% in the exercise group compared to 73.9% in the education group. This equates to a 28% relative reduction in risk.

• Overall survival also improved significantly — At eight years, overall survival reached 90.3% in the exercise group and 83.2% in the education group. This represents a 37% relative reduction in the risk of death. The magnitude of this effect is comparable to some conventional cancer therapies, highlighting the clinical value of structured physical activity in recovery.

• Exercise is a beneficial part of standard post-treatment cancer care — According to the study co-chair, Janette Vardy, a Professor at the Faculty of Medicine in Health at the University of Sydney:

“Based on our results, what we should definitely see is that a structured exercise program should be being offered to people at the latest for when they finish their chemotherapy. This shows that exercise isn’t just beneficial, it can be lifesaving.

Something as simple as physical activity can significantly improve life expectancy and long-term outcomes for people with colon cancer. Our findings will change the way we treat colon cancer.”5

Earlier Research Provides More Insight Into the Mechanisms of Exercise

The New England Journal of Medicine study is not the first to link physical activity with better colon cancer outcomes. A separate review, published in Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology, also found that consistent physical activity is associated with improved survival and lower recurrence in people diagnosed with colon cancer. The review outlined several biological mechanisms that may explain how exercise affects tumor progression and patient outcomes:6

• Shear pressure from increased blood flow may disrupt tumor processes — Exercise increases cardiac output and blood velocity, creating mechanical forces (shear pressure) along the vascular walls. These forces influence how cancer cells interact with blood vessels and impact the progression or spread of colon cancer.

• Exercise modifies the systemic milieu — Regular physical activity alters the body’s internal hormonal and metabolic environment. These changes, referred to as shifts in the systemic milieu, help reduce factors that support tumor growth and progression.

• Immune function is enhanced by physical activity — The review identified immune activation as a possible mechanism. Exercise improves immune surveillance and supports the body’s ability to detect and respond to cancer cells.

• Extracellular vesicles may mediate signaling effects — Physical activity prompts the release of extracellular vesicles from skeletal muscles. These vesicles contain proteins, microRNAs, and other molecules that influence tumor biology, including inflammation, angiogenesis, and cell signaling.

The cumulative epidemiological and mechanistic evidence strongly supports the integration of structured movement into post-treatment care for colon cancer. For a deeper look at another factor influencing colon cancer development and progression, read “Gut Bacteria’s Hidden Role in Colon Cancer Risk.”

Strength Training Also Helps Reduce Cancer Risk

Another study adds further weight to the case for exercise as a tool in cancer prevention and long-term health, this time with a focus on muscle-strengthening activities. Published in the British Journal of Sports Medicine,7 this large systematic review and meta-analysis examined 16 prospective cohort studies involving more than half a million participants, most of whom were tracked for 10 to 25 years.

• Strength training lowered the risk of several major diseases — Resistance-based activities were associated with a 10% to 17% lower risk of death from any cause, along with significantly lower incidence of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, lung cancer, and all cancers combined. These effects were independent of whether the person also did aerobic exercise, highlighting a distinct physiological role for strength work in chronic disease prevention.

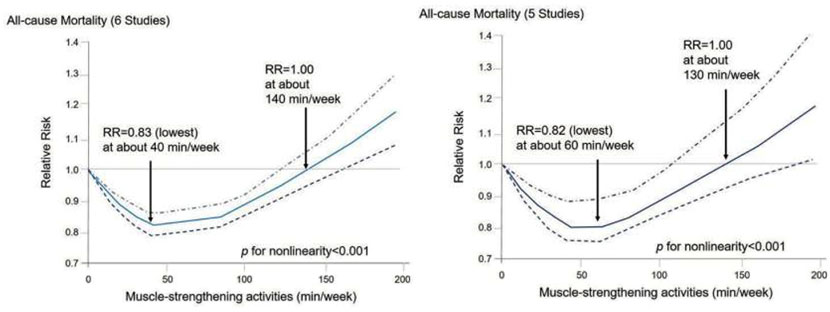

• Optimal benefit was seen at moderate weekly doses — The analysis showed the most benefit from 30 to 60 minutes per week of strength training. Relative risk for all-cause mortality reached its lowest point around 40 minutes weekly, while cardiovascular disease saw the steepest drop near 60 minutes.

Beyond those ranges, the protective effect flattened or reversed slightly, which the authors interpret as a possible stress threshold or overuse effect in some populations. For most adults, this translates to two 20- to 30-minute sessions per week.

• Combining strength and cardio amplified results — Participants who did both muscle-strengthening and aerobic activities experienced even greater benefits. The combination was linked to a 40% lower risk of all-cause mortality, a 46% lower risk of cardiovascular death, and a 28% lower risk of dying from cancer.

• Underlying mechanisms likely involve muscle-driven metabolic regulation — Strength training increases or maintains lean muscle mass, which in turn improves insulin sensitivity, glucose metabolism, and systemic inflammation — factors linked to cancer and metabolic disease risk. The review highlights that skeletal muscle plays a direct role in metabolic control, making it a relevant tissue in cancer biology and immune function.

This study provides strong evidence that strength training isn’t just about musculoskeletal benefits. It plays a broader role in metabolic and cardiovascular health, and offers protective effects against cancer when practiced in moderation.

What’s the Sweet Spot for Exercise Volume?

A comprehensive meta-analysis published in Missouri Medicine explored how different types and volumes of physical activity influence overall health and life expectancy to better understand which patterns of movement offer the greatest protection.8

• Moderate activity was consistently beneficial with no upper limit — Moderate physical activity, such as walking, gardening, housework, or recreational cycling, was associated with steady, continuous reductions in cardiovascular and all-cause mortality. In other words, the more people engaged in these moderate forms of movement, the greater the benefit, with no sign of harm even at high volumes.

In addition, activities done for fun, like team sports, racquet games, or active play, had surprisingly strong links to long-term health. These forms of movement tend to be social, enjoyable, and easier to sustain. They may not always feel like workouts, but they still offer protective effects for the heart and brain.

• Vigorous exercises delivered benefits up to a point — The benefits of vigorous activities like running or high-intensity interval training began to level off around 75 minutes per week.

Pushing beyond that threshold didn’t offer more protection, and for some people, especially those in midlife, it slightly increased cardiovascular risks like atrial fibrillation. The takeaway is not to avoid vigorous activity, but to recognize that moderation matters, even when you’re training hard.

• Strength training followed a different pattern entirely — When practiced in balanced doses, strength training supports muscle mass, bone density, metabolism, insulin sensitivity, and even mood and cognitive function. But when overdone, it can backfire.

The graph below from the meta-analysis shows the J-shaped dose-response for strength training activities and all-cause mortality. As you can see, the benefit maxes out right around 40 to 60 minutes a week. Beyond that, you’re losing benefit:

Once you get 130 to 140 minutes of strength training per week, your longevity benefit becomes the same as if you weren’t doing anything. Moreover, if you train for three to four hours a week, you actually end up with worse long-term survival than people who don’t strength train.

Ultimately, the Missouri study confirms that more is not always better. For a closer look at how to get that balance right, read “Nailing the Sweet Spots for Exercise Volume.”

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) About Exercise and Colon Cancer

Q: How common is colon cancer?

A: Colon cancer is the third most commonly diagnosed cancer worldwide and the second leading cause of cancer-related death. In the United States alone, more than 150,000 people are diagnosed each year, and over 50,000 die from the disease. Cases are also rising in adults under 50.

Q: Can exercise lower the risk of colon cancer coming back after treatment?

A: Yes, emerging research strongly supports this idea. The CHALLENGE trial, a large international study published in the New England Journal of Medicine, found that colon cancer survivors who followed a structured three-year exercise program had significantly lower recurrence rates and higher overall survival compared to those who received standard health education.

Q: What kind of exercise is best for colon cancer recovery?

A: Moderate-intensity aerobic activity, such as brisk walking or light jogging, was the focus of the CHALLENGE trial. Participants who consistently met the weekly goal of 20 MET-hours (roughly five one-hour brisk walks) experienced the greatest benefit. The program emphasized consistency, gradual progression, and long-term adherence rather than intensity.

Q: Is combining cardio and strength training better than doing one type of exercise?

A: Yes. Research shows that combining aerobic and strength training results in greater reductions in mortality than doing either alone. People who regularly did both types of activity had a 28% lower risk of cancer-related death, a 46% lower risk of cardiovascular death, and a 40% lower risk of death from any cause.

Q: What are the biological reasons exercise helps fight colon cancer?

A: Exercise affects cancer biology in several ways. It improves insulin sensitivity and lowers inflammation, both of which are associated with reduced tumor growth. It increases blood flow and vascular shear stress, which may disrupt cancer cell circulation. Physical activity also boosts immune system function and prompts the release of extracellular vesicles that influence tumor signaling.