The same federal guidelines that once told Americans to eat 11 servings of carbs every day might soon advise against consuming any alcohol.

If so, the new recommendation should be taken just as seriously as the old one.

Those new federal dietary guidelines, set to be published later this year, could be the culmination of a yearslong effort by anti-alcohol activists and public health officials. To get this far, they’ve worked to shut out competing points of view and promulgate an official opinion that breaks with the prevailing scientific consensus about alcohol.

Whether that effort succeeds or fails, and whether Americans take the new advice seriously or ignore it while pouring another round, the attempt to make America dry again illustrates what today’s public health leaders value—and what they don’t.

The Pyramid

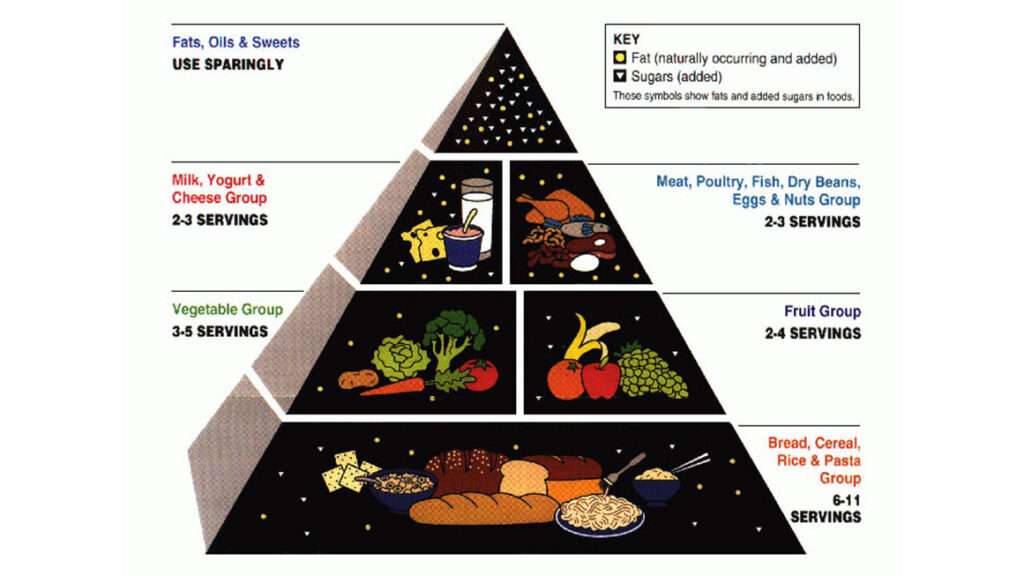

The federal dietary guidelines have been published every five years since 1980, but the thing you’re almost certainly picturing in your head right now is from the 1990 edition: A black triangle composed of six building blocks containing brightly colored edibles. Those images represented the proportions in which federal wise men recommended we consume those foods.

Yes, the “food pyramid.”

As government-backed public health marketing goes, the food pyramid was genius. For kids growing up in the 1990s, like me, it was a ubiquitous reminder to eat healthy—or what the federal government then mistakenly believed was healthy—plastered on school cafeteria walls and the backs of cereal boxes. The pyramid was based on recommendations from a World Health Organization (WHO) study group originally published in the late 1980s. Soon after, it was adopted, in a slightly modified version, by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) and Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), which collaborate on the dietary guidelines.

It was also quite inaccurate.

Probably the most significant error, and almost certainly the most famous, is the aforementioned recommendation that Americans eat gigantic piles of carbs every day.

That recommendation formed the base—literally—of the pyramid, which recommended daily consumption levels for different food groups: three to five servings of vegetables, two to four servings of fruit, etc. At the bottom of the pyramid sat the category for grains and other carbohydrates, of which Americans were told to consume a whopping 11 servings daily—compared to just two or three servings of meat, eggs, and other proteins.

Today, that ratio seems appalling. Serious dieticians and public health experts now recommend a more balanced diet that includes relatively more fat and protein and far less sugar, which is a by-product of digesting all those carbs.

“Even when the pyramid was being developed, though, nutritionists had long known that some types of fat are essential to health and can reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease. Furthermore, scientists had found little evidence that a high intake of carbohydrates is beneficial,” Scientific American explained in a 2006 article detailing the federal government’s attempt to fix the food pyramid. “After 1992 more and more research showed that the USDA pyramid was grossly flawed. By promoting the consumption of all complex carbohydrates and eschewing all fats and oils, the pyramid provided misleading guidance. In short, not all fats are bad for you, and by no means are all complex carbohydrates good for you.”

Nutritional science, in short, is a complex and nuanced subject. Simplified recommendations might be easiest for the general public to learn and recall, but they are also the most likely to be wrong.

The USDA has updated the food pyramid over the years to reflect that changing understanding of nutritional science, but Americans are considerably less trim and healthy. When the first edition of the federal dietary guidelines was published in 1980, about 15 percent of Americans were obese. Today, that figure is nearly 50 percent.

Yes, the average American is much wealthier—and thus able to purchase a greater amount of calories—than his or her counterpart would have been in 1980. Even so, the trend lines suggest Americans might have been a whole lot healthier over the past four decades if the federal government had never tried to nudge them to eat a certain way in the first place. At the very least, this history ought to underscore the risk that comes with passing off inaccurate or misguided public health guidance as if it were a settled scientific fact.

In fairness, it is difficult to distill complicated science into digestible public health guidelines. The process begins with the formation of an advisory committee, which includes nutritional scientists and public health experts. They meet off and on for about two years—the first meeting of the current advisory committee was in February 2023—to discuss how the latest research should impact the new guidelines. The committee’s work is also guided by USDA and HHS officials, who can provide a series of questions to the group at the outset of the process. Feedback from the general public is also supposed to help shape the outcome.

After what the USDA describes as a “rigorous, protocol-driven methodology,” the advisory committee files a series of suggestions for the new dietary guidelines. Federal officials have the final say, but the influence of the advisory committee can be significant—and the committee’s purview has been growing.

In every cycle up to the year 2000, the advisory committee’s final report was fewer than 100 pages long. In the 2020 cycle, it offered an 835-page report that recommended, among other things, a reduction in the amount of sugar and alcohol Americans consume.

Neither of those recommendations were adopted in 2020, but both figure to be big battles this time around.

The biggest fight now involves alcohol, and in the lead-up to this year’s finalization of the new guidelines, USDA and HHS have subverted their own well-established process to hand outsized influence to a few scientists with ties to an organization that’s been pushing to ban alcohol since before Prohibition.

The Holy Grail

Humans discovered fermentation and started making alcohol, archeologists believe, sometime between 8,000 and 12,000 years ago. Several thousand years later, the first civic governments were formed. The first efforts at restricting alcohol consumption probably followed not long after.

The modern anti-alcohol movement—the temperance movement, as it came to be called—didn’t exist as an organized national and international political entity until 1851. That’s when the leaders of several local anti-alcohol organizations met at a lodge in upstate New York to form the International Organization of Good Templars. The nod to the Knights Templar of the Middle Ages was in recognition of the group’s “crusade” against the scourge of alcohol, and also had to do with the knights’ supposed commitment to sobriety.

In the decades that followed, the Good Templars founded groups across the United States, Canada, and Europe dedicated to “offering a comprehensive approach to solving alcohol problems, not just as individual problems but as family and community problems.” That’s the official description from the website of the nonprofit Movendi International, which traces its roots back to that 1851 meeting.

The group rebranded itself in 2020, perhaps to avoid sounding like it was in pursuit of the Holy Grail—an object that, ironically, might have held alcohol.

Still, Movendi declares itself to be “the premier global network for evidence-based policy solutions and community-based interventions to prevent and reduce harm caused by alcohol.” The organization takes credit for providing training and guidance to figures such as Frances Willard, who played a significant role in getting the 18th Amendment passed in 1919.

Nearly 100 years after America abandoned that misguided experiment with Prohibition, the fight continues. Leading the way in the new charge is Tim Naimi. He may not be a household name, but he has a sizable reputation within the public health field, where he is one of the world’s foremost advocates for limiting alcohol consumption by government fiat.

“This is about more than asking individuals to consider cutting down on their drinking,” Naimi said in 2023. “Yes, that can be important, but governments need to make changes to the broader drinking environment.”

In his most prominent public policy role, Naimi helped draft a 2023 report from the Canadian Center on Substance Use and Addiction (CCSA) that called for updating that country’s dietary guidelines to advise significantly less drinking. It also advocated higher taxes on booze and more warning labels. “Risk thresholds for alcohol use should be set at either two or six standard drinks per week respectively, for both females and males in Canada,” the report concluded, with two drinks per week recommended as the “low risk” level.

Despite widespread media coverage of that recommendation, the Canadian government never officially endorsed it. Movendi, however, has promoted Naimi and his work. He co-chaired the group’s international conference in 2022 and has been a recurring guest on the group’s podcasts to talk about his research into the harms caused by drinking. He lists Movendi among his affiliations on his CCSA disclosures page.

Now Naimi has an opportunity to nudge the American government to take the first steps toward similar changes to the “drinking environment” by recommending changes to the federal government’s dietary guidelines. This is thanks to the Biden administration’s bizarre and still not fully explained decision to change how alcohol would be evaluated as part of the 2025 rewrite of the dietary guidelines.

The Committee

With the food pyramid, following what was meant to be a rigorous scientific process still ended with the feds giving misguided advice. But what the government is doing now may be worse: It is making deliberate choices that are pushing it away from scientific rigor.

Recall the two-step process for building the new dietary guidelines. First, an advisory committee of scientists and public health experts reviews the old guidelines to recommend changes, and then USDA and HHS officials decide which changes to adopt.

Naimi had served on the dietary guidelines advisory committee during the 2020 cycle. In that role, he’d backed a proposal recommending a reduction in men’s alcohol consumption that would have cut the longstanding “no more than two drinks per day” guidance in half, to one drink per day. When the USDA and HHS reviewed the advisory committee’s recommendations in 2020, it rejected that proposal.

The Biden administration, though, arbitrarily chose to remove alcohol from the advisory committee’s purview this time around. It set up a separate review process and handed off control of that review to the Interagency Coordinating Committee on the Prevention of Underage Drinking (ICCPUD), a federal entity created in 2004 to “coordinate all federal agency activities related to the problem of underage drinking.”

The dietary guidelines have nothing to do with underage drinking. The recommended amount of alcohol consumption for Americans under age 21 is zero. With this unprecedented maneuver, however, the Biden administration effectively extended ICCPUD’s mandate to include alcohol consumed by legal adults.

Who did ICCPUD—a federal entity with the sole purpose of reducing drinking—choose to lead this new committee to make recommendations about how much alcohol American adults consume? Naimi.

He’s not the only anti-alcohol activist on the six-member ICCPUD committee. He’s joined by Kevin Shield, who leads an advisory panel on addiction at the WHO, which in 2023 updated its stance to recommend that there is “no safe level of alcohol consumption.” Another member of the committee, Priscilla Martinez-Matyszczyk, is the deputy scientific director for the Alcohol Research Group. While speaking at a conference in May 2024, Martinez-Matyszczyk argued that public health messaging should stress that any amount of drinking increases health risks. The other three members of the committee are experts in mental health, epidemiology, and anesthesiology. None are dieticians or nutritionists.

“Taken together, the group brings years of research—and advocacy—that’s heavily critical of alcohol,” summed up Alcohol Issues Insights, a trade publication, shortly after the committee’s lineup was announced.

A comprehensive set of dietary guidelines rooted in the best, most current version of nutritional science could certainly take these perspectives into account. That’s no scandal. But with the whole process being changed unexpectedly, ICCPUD’s leading role in formulating the new committee, and the people chosen to sit on that committee, questions about how fair this process can be were understandably raised.

In a letter to the heads of the USDA and HHS sent in April, Reps. James Comer (R–Ky.) and Lisa McClain (R–Mich.) said they were “alarmed” to learn that an ICCPUD-led study of alcohol consumption was going to be a factor in the upcoming revision of the federal dietary guidelines.

As they pointed out, Congress had recently authorized $1.3 million to the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) to conduct a study on the relationship between drinking and various health outcomes—including cancer, obesity, and heart disease. In one of the budget bills passed in March 2024, Congress had gone a step further and instructed the two federal departments to “consider the findings and recommendations” of the NASEM report when putting together the 2025 edition of the dietary guidelines.

The ICCPUD study led by Naimi and his allies, however, had not been authorized by Congress. At best, it might be duplicative and wasteful, the lawmakers warned. At worst, it would actively undermine congressional intent. “It is imperative that HHS base the Dietary Guidelines on rigorous, sound, and objective scientific evidence,” the lawmakers stressed, as they asked the departments for more information about why and how the ICCPUD study had even been commissioned.

Months have passed without an adequate response. In late May, a bipartisan group of more than a dozen lawmakers wrote to the HHS and USDA to echo Comer’s and McClain’s complaints and to seek more information. When Comer filed a subpoena in early October to compel the Biden administration to give Congress more information about the ICCPUD study, he wrote that HHS had produced only 31 “responsive documents” despite numerous calls and written messages from his office—detailed at length in the subpoena. Administration officials have repeatedly promised more forthcoming responses that have not yet been produced. What little information had been passed to Comer’s committee was “devoid of any internal documents or communications that would provide transparency to alleviate the Committee’s concerns about the delegation of its authority to ICCPUD,” he wrote.

A week after the subpoena, more than 100 members of Congress signed a new letter condemning the ICCPUD study and requesting that it be shut down. “The secretive process at ICCPUD and the concept of original research on adult alcohol consumption by a committee tasked with preventing underage drinking, jeopardizes the credibility of ICCPUD and its ability to continue its primary role of helping the nation prevent underage drinking,” those lawmakers wrote.

Movendi responded by denouncing what it called “interference” by Congress and said alcohol industry lobbying was to blame.

Lobbyists for the alcohol industry are up in arms. In public comments filed in August, the Distilled Spirits Council of the United States (DISCUS), which represents spirits manufacturers, took the ICCPUD commission to task for myriad signs of bias—including Naimi’s ties to Movendi and Shield’s work with the WHO.

On committees overseen by NASEM, concerns like that would be resolved by removing certain individuals or by ensuring that “an individual with the counterviewpoint” serves on the committee as well, DISCUS noted. The ICCPUD committee is operating with no such requirements, and the deck seems to be stacked with prohibitionists.

The alcohol industry is also worried that Naimi’s committee is including factors that have never been part of the dietary guidelines.

“These are not cardiologists or medical researchers, but substance abuse experts, many of whom have made their careers looking into alcoholism and how governments can reduce harmful drinking,” Wine Spectator Senior Editor for News Mitch Frank wrote in September. “Not only will they look at health issues that the dietary guidelines traditionally cover—such as cancer, heart disease and diabetes—but also at traffic accidents and violence involving intoxicated people.”

Groups representing the alcohol industry are undeniably self-interested when it comes to possible changes to the dietary guidelines—and understandably worried about how stricter federal guidelines could affect their member companies’ bottom lines.

Both the alcohol industry and the members of the ICCPUD study committee should be regarded as biased. But only one of those groups is in a position to pass their perspective into official federal guidance.

The Bright Line

Naimi’s views on drinking are not subtle or nuanced.

“The simple message that’s best supported by the evidence is that, if you drink, less is better when it comes to health,” Naimi told the Associated Press last year.

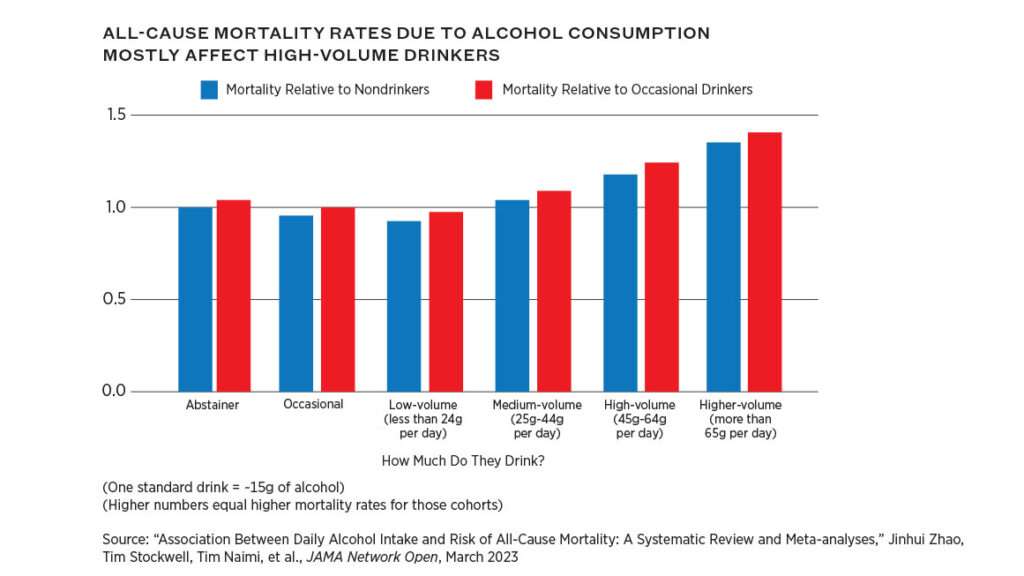

He was referring to a 2023 study—a study he co-authored—published in JAMA Network Open that found individuals who drink regularly are likely to die at a younger age than those who do not drink at all. That study claimed to correct statistical mistakes in over 100 previous reports analyzing the relationship between alcohol and mortality, like a widely cited 1997 one that found individuals who have at least one alcoholic drink per day were more than 30 percent less likely to die from cardiovascular disease than those who didn’t drink at all.

Naimi’s report is part of a shifting trend in alcohol-related studies, including some that have linked drinking to high blood pressure and higher cancer rates.

Rather than merely challenge the established science on booze, however, Naimi and other public health researchers are trying to establish a new bright line—one that Movendi is thrilled to promote: No amount of alcohol is safe.

The WHO, which originally promoted the data that led to the flawed 1990s food pyramid, recently adopted this guidance. In December 2022, the WHO issued a statement declaring that “when it comes to alcohol consumption, there is no safe amount that does not affect health.”

Alcohol comes with a certain level of risk, of course. The health and safety risks of intoxication, heavy drinking, and alcoholism are well known. The key question that any moderate drinker would want answered—and what should concern the bureaucrats drawing up the dietary guidelines—is at what point that risk becomes significant.

On that point, the science is a long way from settled, despite what Naimi and the WHO might claim.

In fact, the congressionally appointed NASEM study, published in December, points in the complete opposite direction. It found that “compared with never consuming alcohol, moderate alcohol consumption is associated with lower all-cause mortality.” Additionally, the study found that moderate drinking is associated with “a lower risk of cardiovascular mortality in both men and women.”

There are difficulties in measuring the health effects of moderate drinking, which the NASEM study also acknowledges. Not everyone is honest with doctors or survey takers about their consumption, and that consumption is likely to fluctuate significantly from day to day and week to week. In highlighting those factors, study committee chair Ned Calonge advocated additional research into how moderate drinking affects health.

That sort of humility is lacking in Naimi’s and the WHO’s outlook. They could use a bit more of it. If you dig into the details of Naimi’s 2023 study that forms the backbone of the “no safe level” claim, for example, you’ll find that moderate drinking has almost no impact on life expectancy. The statistically significant change in life expectancy occurred for men who have more than three drinks per day and women who have more than two.

In other words, it seems to confirm the existing dietary guidelines, not demand that they be changed.

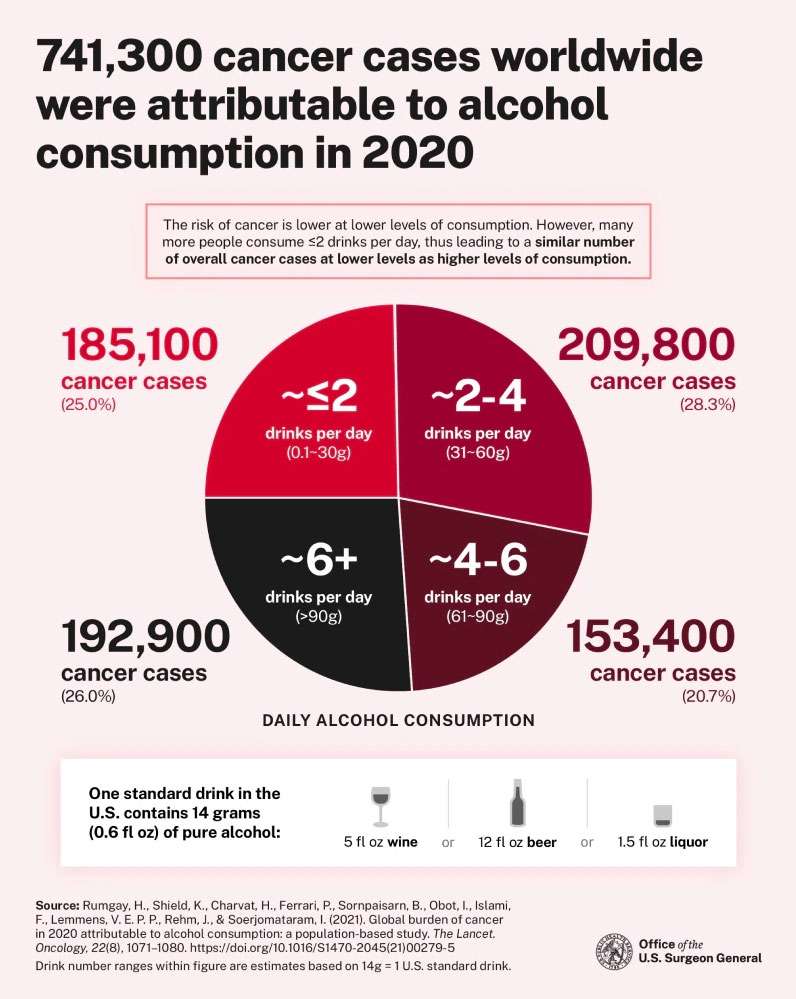

The same is true for a recent headline-grabbing report from former Surgeon General Vivek Murthy that linked alcohol consumption with higher cancer risk. Murthy has called for more warning labels on alcohol to help consumers know that even a single drink can increase the risk of getting cancer.

But that’s not what his own data seem to show. Of the more than 740,000 cases of cancer worldwide in 2020 that Murthy says could have been prevented by abstaining from alcohol, more than 75 percent are attributable to people who had more than two drinks per day.

Murthy’s findings, then, simply restate what’s already well known: Routinely drinking a lot of alcohol is dangerous to one’s health. Drinking less than that, unsurprisingly, is not as bad.

This might seem like common sense. It is. But a well-organized campaign is now positioned to embed a very different set of conclusions into the government’s official dietary guidance.

The Question

Yes, these are just guidelines. And, yes, few Americans probably pay much attention to what the government says they should eat and drink.

But a dramatic change in the dietary guidelines—along the lines of the change that the WHO adopted last year—could make it easier for other changes to follow. This isn’t the blunt instrument the temperance movement used to implement Prohibition over a century ago. It’s a slow-burn effort that dresses up cherry-picked data as scientific consensus, potentially inserted into public policy by a biased committee operating outside congressional authorization.

It also ignores the basic realities of human existence. Yes, alcohol is a drug. Yes, it can be dangerous when used incorrectly or relied upon too much. Yes, drinking a lot isn’t healthy.

But tradeoffs always exist. Depending on who you are, alcohol is a social lubricant, a hobby, or more. The existence of some risk does not mean there are no benefits, and anyone motivated purely by a desire to maximize the amount of time spent on this celestial plane is probably already staying away from booze.

The big question here: Why does the federal government have dietary guidelines?

I don’t mean that in the sense of whether it’s a proper role of government to draw these things up. (Even though it probably isn’t.)

I mean, what’s the purpose the guidelines are meant to serve? Are they rules for maximizing life expectancy, or somewhat vague and occasionally suspect guardrails against dangerously unhealthy behavior? Since the 1980s, they have largely been the latter.

When it comes to alcohol, Naimi is trying to make them the former.

“Alcohol is a legal substance that causes lots of problems, many of which are highly preventable with effective public policies, but it’s going to take a lot of political work to get there,” he told a Canadian journalist in 2023, seemingly leaving little doubt that his professional goal is not merely changing government guidelines for informational purposes, but using the levers of policy to reduce alcohol consumption.

But again, tradeoffs exist.

“If the government goes through with a ‘no safe level’ declaration or a reduction in the drinking guidelines, the consequences will be more significant than many realize,” says C. Jarrett Dieterle, a senior fellow at the R Street Institute, who has followed these developments closely.

Reduced consumer demand for booze would be only one of the outcomes—though obviously a significant one for the alcohol industry. Polling suggests that up to two-thirds of younger Americans would curtail their drinking if the dietary guidelines suggest doing so.

The bigger thing, says Dieterle, is that a “no safe level” declaration could trigger a series of class-action lawsuits against alcohol producers—similar to those unleashed against tobacco companies in the 1990s.

Even if the litigation isn’t successful or doesn’t ruin the industry, it would bring added costs and risks that could drive some producers (smaller, craft operations, in particular) out of the market. Combined with the potential harm of higher tariffs, the alcohol industry is facing a rough year. Even if the dietary guidelines are ignored by most Americans, small margins can make a difference.

“Mix it all together and it’s starting to look like the industry will be forced to swallow a poisonous cocktail of bad government policy,” Dieterle tells Reason.

It might be “a lot of political work” to achieve their aims, but Naimi and his prohibitionist allies have clearly decided where to start.

The post The New Prohibitionists Are Hijacking Federal Dietary Guidelines appeared first on Reason.com.